Flint Water Crisis is Unexpected Opening for City Water Systems

Climate conditions are changing U.S. water systems and providing space for innovation.

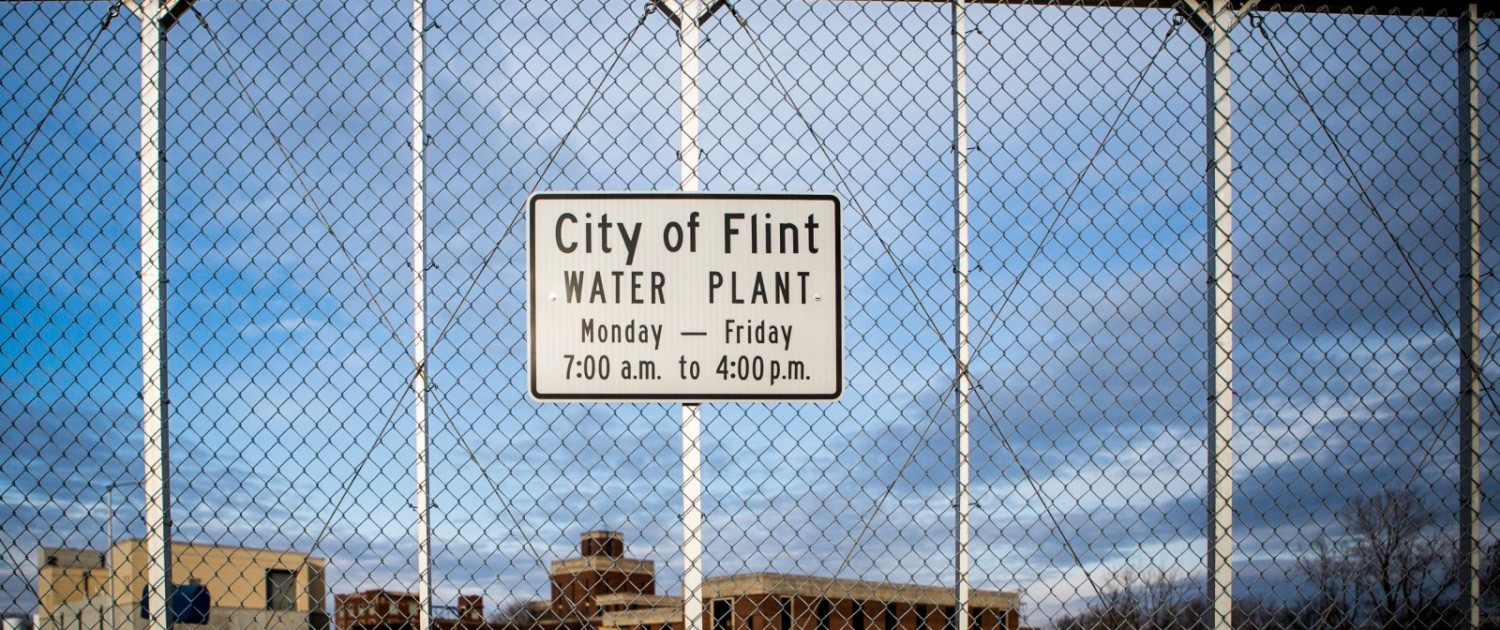

Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue Aging water pipes and a lack of proper corrosion control measures created a lead contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan and focused national attention on water infrastructure. The crisis provides an opportunity for cities to rethink how they manage, treat, and deliver water in an era of climate change.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

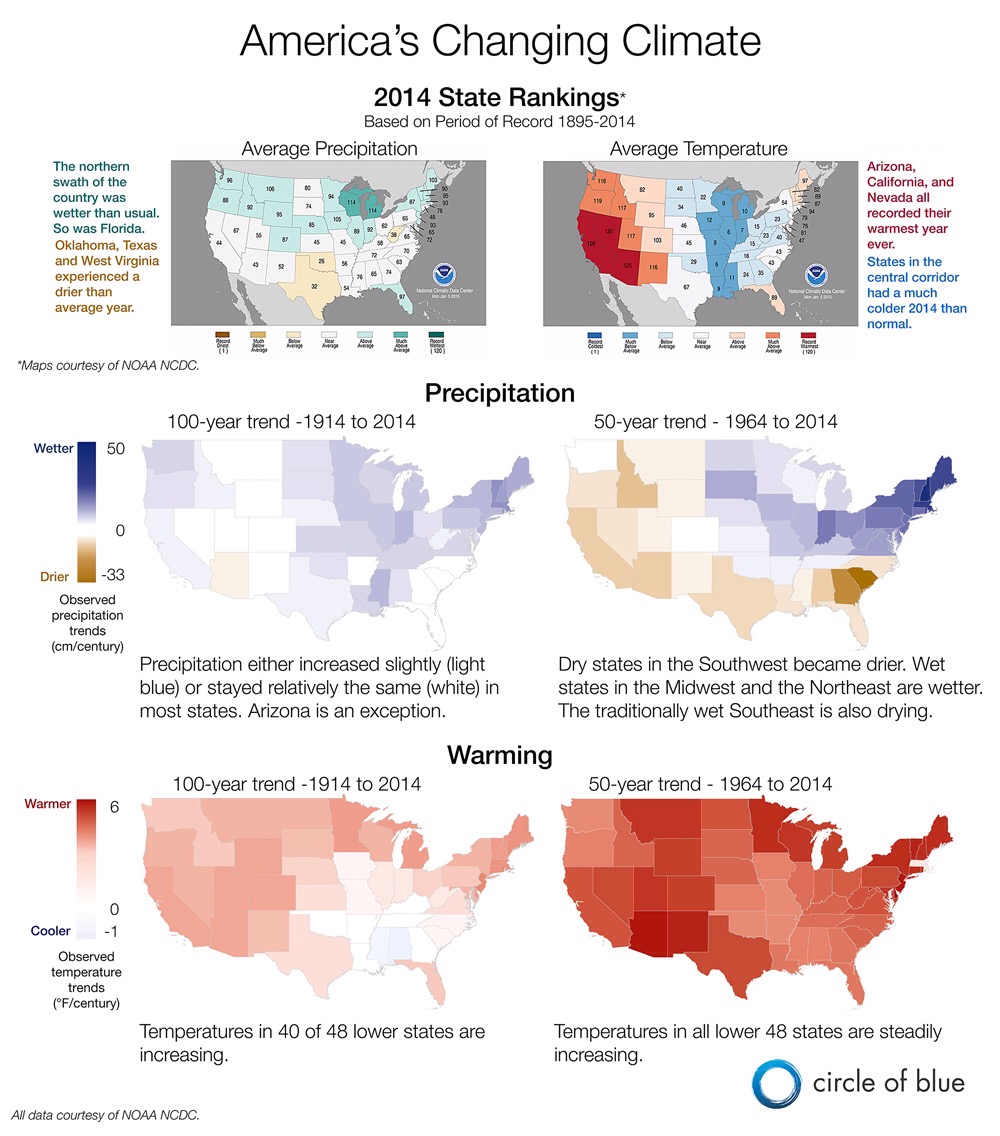

The old 20th-century story of America’s aging water systems, and the expensive repairs that are necessary, is taking on very new dimensions in the 21st century as cities are challenged by much riskier ecological conditions. Not only are water transport networks collapsing as a result of their age and shoddy maintenance, city water supply and wastewater treatment networks are being battered by deeper droughts, more powerful storms, and rising sea levels.

The result is that supplies of clean, reliable water are not nearly as assured across the United States as they once were. Yet out of this morass of risk has come a new municipal reckoning about water supply and treatment as utilities rethink their systems and adapt to changing ecological conditions.

“Change comes in response to a real or perceived crisis, and this is something we often refer to as a window of opportunity,” David Sedlak, co-director of the Berkeley Water Center at the University of California, Berkeley, told Circle of Blue. “When the window is open, it only stays open for a little while. We have to figure out the right solutions, because once that moment is gone, the public stops paying attention. It’s encouraging that it’s not just the water utility people paying attention to this problem now, it’s elected officials and community leaders paying attention to it.”

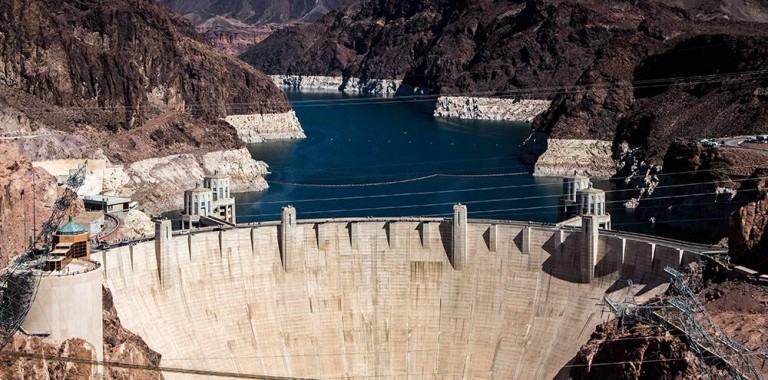

The challenges for water suppliers are much more difficult in an era of unpredictable and extreme weather. In the western United States, for example, severe droughts are altering cities’ customary sources of water. Spring snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains, where many western states get their drinking water, declined at more than 90 percent of the sites measured between 1955 and 2015, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

States in the South and Midwest also face scarcer water supplies in the future, while states in the Northeast and in coastal areas will likely experience more frequent and severe floods. Stronger rainstorms in Ohio have contributed to the excessive runoff of nutrients into Lake Erie, triggering massive blooms of toxic algae that shut down public water supplies.

This is an opportunity to build something different, rather than just replacing the parts and building a vintage 1970s treatment plant for 21st-century problems.

Communities already affected by the new climate realities are pushing utilities to experiment with ways to treat and provide water. While many of the practices are not new – including water recycling and green infrastructure—they have not yet become widespread in the United States due to their cost and the initial risk involved with implementation.

That may be changing. At the same time climate factors are placing more stress on water systems, it is becoming clear that many of those systems are dangerously outdated.

National attention to water supply trends, largely ignored by the public for decades, have bounced to the top of civic priorities in recent months largely due to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, where city residents received lead-laced drinking water for nearly two years.

The Flint case, the result of government neglect and incompetence, is an outlier unlikely to be repeated at a large scale, according to water experts. Nonetheless, a growing number of communities and schools across the country are finding evidence of high lead levels in their own drinking water systems from lead service lines to homes. The public health emergency is forcing water managers and government leaders to look closely at an uncomfortable reality: America’s water systems are old, underfunded, and ill-suited for the changing social and environmental conditions of a new century.

“We’re going to be replacing those drinking water treatment plants and wastewater treatment plants in the next decade or so,” said David Sedlak of the Berkeley Water Center. “This is an opportunity to build something different, rather than just replacing the parts and building a vintage 1970s treatment plant for 21st-century problems.”

While the vast majority of water systems in the United States continue to operate safely, many drinking water and wastewater treatment plants, installed in the mid-20th century, are nearing the end of their useful lives. Water mains, the major pipes that carry drinking water to homes and businesses, are decades –sometimes centuries—old in cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Milwaukee. The cost to replace and make necessary expansions to drinking water pipe networks alone could reach $US 1 trillion over the next 25 years in the United States, according to 2012 estimates by the American Water Works Association (AWWA).

“We’re a relatively young country and we have not arrived at this moment before, where all of these many miles of pipe have been in the ground,” Greg Kail, director of communications at AWWA, told Circle of Blue. “They last a long, long time, but they don’t last forever.”

Fostering Water Innovation

Some of the technologies cities are beginning to embrace include water recycling and the use of green infrastructure and natural systems to help filter and treat water. For example, the Orange County Water District near Los Angeles completed a water recycling plant in 2008 that treats wastewater and recharges aquifers that supply the region with drinking water. From Milwaukee to Philadelphia to Portland, Oregon, cities are employing permeable pavement, green roofs, and wetlands to reduce overflows of stormwater and sewage.

Modesto and Turlock, two California Central Valley cities, are working with the Del Puerto Water District to send recycled wastewater to irrigate thousands of acres of orchards. Oakland, California cleanses its stormwater with a network of creeks it has restored to their natural, water-filtering condition.

But for the practices to become widespread, there will need to be significant changes to the laws that protect and regulate water, as well as to the incentives for cities to innovate.

We’re a relatively young country and we have not arrived at this moment before.

One challenge for cities that wish to adopt water recycling, for example, is a lack of experience at the municipal and state level in regions where the technology has not yet been used. Moreover, the portions of the federal Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act that are meant to protect drinking water sources are not tailored to the use of recycled water. That means rules regulating what can be discharged into wastewater are aimed at keeping treatment plants functioning and minimizing the harm to downstream ecosystems, not prepping the water for reuse.

“We have a system of thinking about wastewater that is from the 1970s, when the main concern was that someone was going to put something into the sewer that would knock out the system,” Sedlak said. “Those source control regulations were never written with the idea that this might be a drinking water supply. If we’re really serious about potable water recycling, we have to think about our sewer systems in the same way as a watershed, and make industrial discharge requirements more stringent.”

Another obstacle to implementing innovative urban water infrastructure is the huge cost, in terms of finances and risk. Water managers put their careers on the line if new water infrastructure or management approaches fail. If the system is working in the short-term, there is little incentive for utilities to experiment, or ask public officials for large budgets to pursue risky projects.

“There’s a pretty large penalty for being innovative and failing, and a relatively small reward for being innovative and succeeding,” said Sedlak.

Government grants can help underwrite the cost of such projects and share the risk they involve, creating demonstration projects that could benefit other areas of the country, Sedlak added.

Summoning Political Will and Public Support

Drumming up more funding for water infrastructure projects is key for building new types of water and sewer systems and fixing aging pipes—the need for which is unlikely to disappear even with more innovative treatment plants.

“One of the key differentiators between developed countries and ones that struggle in the global economy is the reliability of their water infrastructure,” said AWWA’s Kail. “Water infrastructure that provides safe water, reliably around the clock, provides for the protection of public health, a successful economy, the underrated importance of fire protection, and the overall quality of life that we, in the United States, take for granted. We’ve become accustomed to those water systems delivering for the most part without fail, and that’s a good thing, but the longer we defer needed investment, the more likely we are to have situations where that service is at risk.”

Most water utilities in the United States are publicly owned, and rely on voter-approved bonds or government loans and grants to finance major infrastructure projects. Federal programs like the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund help by providing financial assistance to improve the quality of drinking water sources, drinking water treatment, and water distribution systems. Another federal program, the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act that was approved in 2014, could also add a much needed boost to infrastructure investment. So far, however, Congress has not appropriated any funds to WIFIA beyond those needed to set up the program.

“When it becomes clear that the existing system no longer is serving the city’s needs, and they need to invest in a new approach, they can’t do it with the normal revenue streams they have,” Sedlak said. “Customers just paying monthly bills is often not enough to jump to new types of approaches. That either requires a bond or some sort of government grant to build new kinds of infrastructure. That doesn’t happen until there is a real or perceived emergency.”

Now that a number of emergencies have occurred—the California drought, the toxic algae blooms in lake Erie, and Flint’s lead-contaminated crisis—water utilities have an opportunity to communicate their needs to the public and elected officials who control the purse strings.

“It’s human nature to not want to pay more for something you already are receiving,” Kail said. “For the most part, [water] doesn’t seem to be a problem for most of us.”

“Sometimes there’s not the political will to push for water infrastructure as a major issue,” he continued. “But frequently that’s because we as consumers don’t recognize the value of those systems.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!