Texas High Plains Prepare for Agriculture Without Irrigation

Southern farmers are making changes now to wean themselves from the Ogallala Aquifer, a water source that gave rise to industrial agriculture and modern life on America’s plains.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

LUBBOCK, Texas — Cotton farming in west Texas, among the nation’s driest regions, is possible only because there is water — millions of gallons from wells drilled into the Ogallala Aquifer, which runs from here to Nebraska. Evidence of the famed aquifer’s value is in the ruddy soil behind a federal agricultural research center, where an irrigated field of cotton grows thigh-high, dense with puffy knots of white fiber signaling it is ready for late-October harvest.

But in a second field to the east, the contrast astonishes. The plants in the adjacent plot are skeletal and barely tall enough to reach a man’s knee. The few cotton bolls that did bud look as pathetic as a bald Charlie Brown Christmas tree hung with a handful of ornaments.

The second plot reflects a long-predicted change in water supply that is producing unsettling consequences for agriculture in one of the country’s important cotton and wheat belts. After decades of overpumping, the Ogallala Aquifer, the water supply that this region has relied on since the 1950s, is gradually being pumped dry. The dryland cotton field is part of a program of research undertaken by scientists and farmers here who are racing to figure out how to be productive in a dry era that uses much less groundwater and depends more on the erratic rains.

The Ogallala Aquifer’s decline is not a surprise. Scientists, agricultural specialists, and researchers have been asserting for decades that the volume of water in the aquifer, like the oil in a well, is finite. Still, despite having time to prepare, the urgency of finding solutions is real, and water managers are just now testing new pumping restrictions that are designed to prolong the aquifer’s life. All of the 1.8 million hectares (4.4 million acres) that are irrigated in the Texas high plains tap into the Ogallala.

To keep the farm-based economy chugging, water districts in the Texas high plains are restricting withdrawals from the aquifer. Looking ahead, energy evangelists see a new economic beginning in the region’s ample wind currents. But the environmental, legal, and cultural hurdles to achieve these adaptations show just how difficult the transition away from irrigated agriculture will be.

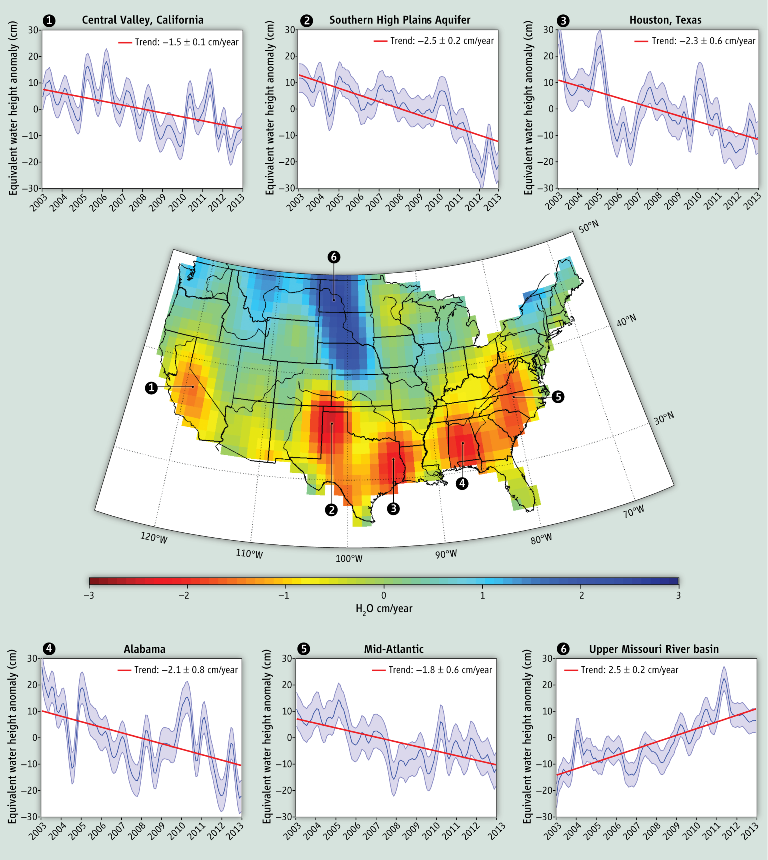

Texas is not alone. The state is merely one of the first in line for the economic and social reckoning that some of the world’s agricultural hotspots will face in the coming decades. California’s Central Valley, India’s Gangetic Plain, the North China Plain, and the Arabian Peninsula — all are key farming regions, all are sucking out groundwater at unsustainable rates. Some 1.7 billion people, roughly a quarter of the world’s population, live in areas where aquifers are under stress, according to a recent study in Nature.

“As we in Lubbock, Texas, are today, so you will be in the future,” James Mahan told Circle of Blue. Mahan is a plant physiologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) who studies crop stress at the research center. “The global water crisis is real, and there’s no sneaky way out of it.”

Regulation During Stressful Times

Three-fifths of the 3 million hectares (7.5 million acres) farmed in the Texas high plains — the center of U.S. cotton production — are now irrigated, down 25 percent from a peak in 1974. Given the region’s rainfall and the aquifer’s recharge rates, however, only 10 to 20 percent of the land that is now irrigated can be sustainably irrigated, argues the Texas Water Development Board, a state agency.

–Glenn Schur, chairman

Texas Alliance for Water Conservation

Moreover, the aquifer’s depth is not uniform, so the effects of a falling water table are more severe in certain areas. Thanks to agriculture, which accounts for 96 percent of all withdrawals in the Texas high plains, half the water in the aquifer’s shallow southern end has been used up since intensive pumping began after World War II. In the next few decades, water managers say there will be so little water remaining that the cost of pulling it from deeper and deeper underground will exceed any profit that can be made from applying it to crops. For some farmers, this is already the case.

Though crops can grow in the high plains without irrigation, dryland farming is riskier and less profitable because rainfall is so sporadic here. In general, leaving the fields to the whims of Mother Nature can cut yields in half compared to an irrigated crop. And if insufficient precipitation meets wiltingly high temperatures, a farmer might produce nothing but dirt, as was the case in 2011, when record heat and scant moisture caused cotton production in Texas to plunge by 55 percent, according to the USDA.

A little certainty — or as much as is possible on the plains — is what the High Plains Water District, which covers 16 counties that use the Ogallala, is trying to provide.

In 2005, the Texas legislature required the state’s 16 groundwater management areas to coordinate with the 96 water districts on a new planning process. Each area had to submit a plan for how much groundwater would remain in 50 years, a standard called “desired future conditions.”

The High Plains Water District decided that it wanted to withdraw no more than half of the existing water — which itself is half of what was in the aquifer when industrial agriculture begin in the 1950s — by 2060. To accomplish this, the district set gradually decreasing annual pumping limits.

The restrictions were supposed to take effect last year, but the district’s board of directors delayed enforcement of the rules until 2014.

“The board felt the delay was needed so producers could be accustomed to the reporting procedures and they could get in the routine of doing so,” said Carmon McCain, a representative of the High Plains Water District.

Soon, reporting water withdrawals could become a requirement statewide. A state senator from the plains city of Amarillo introduced a bill in the legislature in February that would force most farmers to track their groundwater use and report it to the state.

Meanwhile, the first deadline to report data to the High Plains Water District came this March.

What Is Fair?

The exasperating and complex negotiation between the present and the future is manifest in Barry Evans, who grows cotton, wheat, and sorghum on his farm an hour north of Lubbock.

Evans — a former president of Plains Cotton Growers, an industry group — reads Darwin and books on soil science. Nearly two decades ago, he began planting seeds without plowing the field, a no-till technique that preserves precious soil moisture and organic material.

“Now we’re making our soil better, not raping it,” he says, while walking through rows of cotton.

Along with soil preservation, water conservation runs through the entire business model, Glenn Schur told Circle of Blue. According to Schur, a farmer and the chairman of the Texas Alliance for Water Conservation, energy is becoming a big component of water management, especially as the aquifer shrinks. Energy bills have tripled compared to a decade ago, now that water has to be pulled from deeper underground.

“I don’t want to apply any more water than I have to,” Schur said. “It’s not just an environmental issue. It’s an economic sustainability issue. Every acre-inch I can save puts money in my pocket.”

Evans and Schur are both every bit the modern farmer — educated, technology-savvy, and focused on the bottom line. Evans knows the Ogallala is running low, which is why he chose to go no-till in 1996. Yet he does not fully endorse the High Plains Water District’s plan to restrict water withdrawals.

“I see the need, and I’m not opposed to regulations,” he said. “But you have to do it in a way that’s not burdensome for farmers.”

When asked how that regulatory weight could be better distributed, Evans responded, “I don’t know. That’s a tough one.”

Community apprehension about the district’s water restrictions is just one source of uncertainty; another source is legal.

Amy Hardberger, an assistant professor of law at St. Mary’s University, said the groundwater districts in this part of Texas are some of the most forward-thinking districts in the state. A recent court case, however, threatens the metering requirement and volume caps on water withdrawals that several districts have implemented.

The Texas Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that landowners have a claim to the groundwater below their property. Hardberger said nobody is quite sure about the constitutional implications of the case.

“Where does the right to regulate bump into the Fifth Amendment takings clause?” Hardberger mused during a panel discussion at the Society of Environmental Journalists conference in Lubbock in October. The takings clause requires the government to compensate the owner if private property is seized. “The decision has had a chilling effect for groundwater districts, because they don’t want to be the test case for a takings claim.”

The High Plains Water District has heard threats of a lawsuit, McCain told Circle of Blue, though nothing has been filed.

Winds of Change

What the Texas Panhandle lacks in water, it makes up for in wind. Stout, hair-raising gusts funnel through the treeless plains. Maps from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory rate the region among the top in the United States for wind resources. As of October 2012, Texas accounted for 21 percent of the nation’s installed wind capacity.

Even better for the arid region, wind turbines require no water to generate electricity. The wind, of course, brought the first whiff of a viable agrarian life to settlers on the plains. Long before electrical lines threaded rural land, farmers used windmills to pull water from below. Today, some argue, wind might again be the engine of prosperity.

As the water table drops, an economic overhaul will certainly be needed. Research from the Texas AgriLife Extension Service and Texas Tech University estimates that converting all irrigated acres to dryland acres — an extreme example, to be sure — would result in an annual net loss of $US 1.6 billion and nearly 7,300 jobs in the region. The blow would fall hardest on rural communities where agriculture comprises roughly 75 percent of economic activity.

For some of these farmers wind power is a savior, even now.

The benefits extend to communities, too, argues Ken Starcher, an associate director at the Alternative Energy Institute at West Texas A&M University.

“By having wind power generated in economically depressed counties,” he told Circle of Blue, “you can stabilize the tax base for everyone.”

Wind would be a stranded resource, if not for some significant state-mandated infrastructure investment. Texas is in the midst of a $US 5 billion project to build new transmission lines that will bring wind power from the state’s blustery west to the booming cities of the east, where the demand is. Ratepayers will cover the cost of the project, which grew out of a renewable energy bill passed by the state legislature in 2005.

Starcher reckons that wind turbines will quickly follow in the path of the transmission lines, so long as developers have access to credit and power companies are willing to add wind to their mix.

Wind might not save agriculture here, but it could allow rural communities to endure.

Toward a Brick Wall

Sunset bleeds out slowly on the plains. Marmalade skies linger well after the sun has clocked out. The same might be said of agriculture here — farming’s death notice keeps being delayed. When warning bells rang in the 1970s over water use, farmers became more efficient, opting for low-pressure pivot systems and soil sensors over rudimentary flood irrigation. Yields increased and farming became more profitable, even though water withdrawals remained constant.

–Steve Verett, executive vice president

Plains Cotton Growers

“People have been saying we’re going to run out of water for 40 years,” said Steve Verett, the executive vice president of Plains Cotton Growers. “I’m 60 years old, and water is still here.”

But the biggest gains from efficiency have mostly been cashed in. There are few wasteful irrigation systems left to convert. Drip irrigation installed below ground could bump up water-use efficiency by a couple percentage points, but the jump is small compared to the shift away from flood irrigation. Innovation might yet come from fiddling with genetics to produce crops that can thrive in drought, and researchers and seed companies are working hard at this.

For instance, the researchers at the Lubbock laboratory are looking at different irrigation and planting strategies that produce the best crops with the least amount of water. They are also probing genetic material for traits that allow plants to survive drought, and they are testing whether plants can be “trained” to endure dry periods, similar to a mountaineer acclimating to thin alpine air.

Additionally, a research consortium — including the USDA, the Texas Water Development Board, and Texas Tech University — is studying whether more precipitation will soak into the aquifer if the thousands of small wetlands on the plains, called “playa lakes,” are restored. These playa lake recharge experiments could help individual farmers trap more rainfall.

“Drought research is frighteningly complex,” Mahan said during a phone interview a week after Circle of Blue visited his lab at the USDA’s Cropping Systems Research Laboratory in Lubbock.

New challenges, such as the heat and aridity of climate change, are in the air. Warmer average temperatures will add stress to an already-stressed agricultural system. If rainfall decreases as well, dryland farming will be even more difficult. Out here, water is — and will be — the ultimate limit.

“We’re heading 80 miles per hour toward a brick wall with water use,” Mahan said. “Climate change, right now, is a few branches hitting the windows.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!