Californians, In a Departure, Appear Ready to Support Big Water Spending to Respond to Drought

State leaders face infrastructure decisions now that will have consequences for decades.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Following crucial decisions this year by federal and state leaders to spend nearly $US 2 billion in public investment to relieve the short-term financial symptoms of very dry weather, California lawmakers are now considering spending much larger sums of public money to respond to the long-term economic and ecological threat – a persistent drought, in its third year, that appears to be deepening.

State legislators and Governor Jerry Brown, a Democrat, are considering nearly a dozen proposals to spend $7 billion to $9 billion in taxpayer-backed bonds to produce, transport, and store adequate supplies of fresh water. In contrast to the $2 billion in disaster relief aid, the proposals echoing in the labyrinthine halls of California’s Capitol offer something rarer: a chance not to react but to prepare.

Among the steps that lawmakers are vigorously debating are developing new practices and equipment to clean contaminated groundwater for use as drinking water, building new wastewater recycling plants that can recharge underground reservoirs, fixing leaks in canals and community water systems, and even building new dams and surface reservoirs.

–Anthony Rendon Democratic state assemblyman

The array of ideas, and the developing consensus that big public investments are needed to secure California’s freshwater reserves, also represent a change in how voters perceive the credibility of government to respond to a complex, long-term, and increasingly urgent threat. The politics of austerity that grip much of the rest of the nation, as Tea Party-influenced lawmakers deride new public initiatives for rail transport, clean energy, urban modernization, education, and other public purposes, are not taking hold as California voters consider what to do to diminish the effects of the drought.

“If we do not act soon, funding for critical water infrastructure and programs are in jeopardy, and California will be unprepared for future floods and droughts,” said Assemblyman Anthony Rendon, a Democrat, on March 5 after increasing the funding in his water bond proposal by $US 1 billion, a change that was inspired by his Republican colleagues and public discussions.

Indeed, California voters, lawmakers, and water authorities are generally convinced that more spending to safeguard and supply water in the nation’s largest state will certainly be necessary.

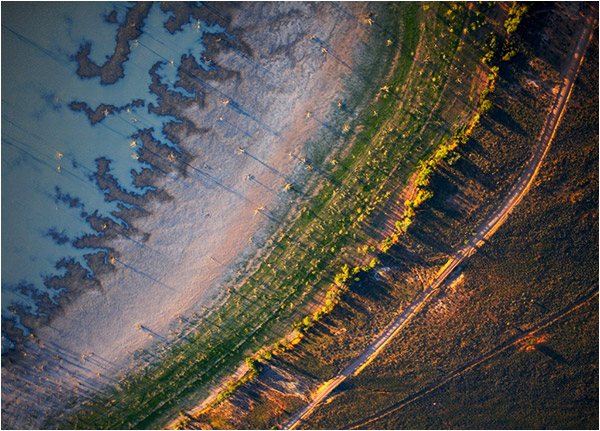

As increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases warm the globe, scientists expect California’s climate to heave between deep droughts and calamitous floods. Though total precipitation may not change, its timing and intensity will be incompatible with the current system of reservoirs, pipes, and canals. Rising seas, for instance, will push saltwater into coastal aquifers and into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, an important fish habitat, a source of drinking water for millions, and a source of irrigation water for the Central Valley, the nation’s top producer of fruits and vegetables.

The water bond, targeted for the November ballot, has a June 26 deadline to pass the legislature. The bond is expected to offer a stout stream of cash to start a water-system overhaul, including new practices and equipment to conserve water on farms and in homes, rejuvenate natural water-storing ecosystems like the Sacramento Delta, and construct reservoirs above and below ground.

“We have to invest in the whole system,” said Tim Quinn, executive director of the Association of California Water Agencies, which represents 450 local water agencies. “That means surface storage to catch flood bounties, delta restoration to move supplies, and cleaning up contaminated basins to store more groundwater. No piece of the bond does that by itself.”

But of all the projects, it is water storage – with a legacy of dam-building and more dams on the table – that promises to attract the most disagreement.

Reaching a Compromise

California has been waiting for the right moment to establish its water infrastructure modernization. Five years ago lawmakers passed a $US 11.1 billion water bond. The proposal came in the midst of the Great Recession, was weighed down with pet projects, and never appeared on the ballot.

A less expensive bond, probably in the $US 7 billion to $US 9 billion range, is the new goal, and water storage is a key component. The campaign to build new storage capacity is supported by California’s most recent water plan, published in January, which asserts that increasing the volume of water held in reservoirs and in aquifers is paramount.

“The bottom line is that we need to expand our state’s storage capacity, whether surface or groundwater, whether big or small,” the five-year plan states. “Today, we need more storage to deal with the effects of drought and climate change on water supplies for both human and ecosystem needs.”

Achieving that objective means capturing more water during wet periods. As global temperatures rise, California will see relatively constant precipitation, but more will fall as rain than as snow and there will be more extreme droughts and floods. Scientists anticipate that the warming atmosphere will eventually cause California to lose its most important natural reservoir – the Sierra Nevada snowpack. This winter, the snowpack is less than one-third its normal depth.

Over the last three years, the nation’s most populous state has slipped into an ecological and social red zone that could, by summer, become a genuine emergency. The nastiest drought in 500 years has drained reservoirs, cut farmland production, and revealed striking inadequacies in how the state uses and manages water. The forecast for the next few weeks shows low probability for rain or snow, meaning that California will likely end its normal winter wet season in April without any more precipitation.

State and federal leaders earlier this year already approved nearly $US 2 billion dollars in emergency drought aid. That money will go directly to farmers who lost a crop, ranchers who lost a herd, and families who lost a farm job.

Americans and their elected leaders are comfortable spending relief aid for disasters. The federal government spent $US 110 billion for Hurricane Katrina recovery, $US 48 billion for Hurricane Sandy, and $US 17 billion in crop insurance payouts after the 2012 drought.

But in an era of austerity, some taxpayers and virtually all conservative lawmakers oppose taxpayer investments for big long-term public projects – port modernizations, research, new forms of less polluting energy.

A water emergency, on the other hand, carries different weight with voters. Texas voters, for example, approved a $US 2 billion water bond last November. Water agencies in Southern California invested $US 12 billion in the last two decades in water storage and conservation – investments that are helping the region ride out the current drought.

What Qualifies As Storage?

The consensus around spending to deal with California’s drought makes itself felt regularly now, and especially in Sacramento, the state capital. Earlier this month, when Anthony Rendon, a Democratic assemblyman and chair of the water resources committee, revealed changes to his $US 6.5 billion bond proposal, his supporting cast was as important as his message.

Standing with Rendon, who represents the Los Angeles suburbs, were Democratic and Republican lawmakers from the Central Valley, an anti-tax, anti-spending Republican stronghold. Also at his side were representatives of the construction industry and labor unions, Democratic allies whose support for building reservoirs would be at odds with many in the party’s environmental wing. The group did not explicitly endorse Rendon’s bond, now pumped up with an additional $US 1 billion for water storage, but its representatives did not decline the invitation to the press conference.

These big-tent coalitions will be necessary as California lawmakers debate how many billions of dollars the state should put into one of the largest bonds ever placed on the ballot.

By virtue of being the first to clear either the Assembly, Rendon’s proposal is an early leader and will be heard in the Senate Natural Resources and Water Committee on March 25. But not only must a water bond pass the legislature by two-thirds. It must also be approved by voters. Rendon said that in six regional bond hearings citizens lobbied for projects that hold water.

“In the Central Valley where communities are hardest hit by the drought and most dependent on farming, the need for greater investment in storage is clear,” Rendon said. “Hundreds of families and farmers attended the last two Central Valley hearings to express their concerns about replenishing our aquifers and preventing the needless loss of water by improving the way we store water that flows through our rivers and streams.”

Rendon’s bond, which, with smaller modifications, now totals $US 8 billion, includes five categories of storage projects eligible for $US 2.5 billion:

-

• Building new surface reservoirs

• Expanding aquifer storage capacity

• Restoring surface reservoir capacity lost to sediment accumulation

• Cleaning contaminated aquifers

• Building or expanding facilities to hold flood waters

All categories have their warts, some more detrimental than others.

Restoring reservoir capacity lost to sediment accumulation, for instance, is neither practical nor cost-effective for large water supply reservoirs, argues Greg Pasternack, an environmental engineer at the University of California, Davis.

Most California reservoirs are not designed with the technical features necessary to flush out sediment, Pasternack said. Even if they were, environmental regulations would work against sending a slurry of mud through hundreds of miles of river bed.

A 2009 University of California, Berkeley study found that 4.5 percent of the state’s reservoir capacity had been consumed by sediment. Roughly 190 reservoirs, or one out of seven in the state, had lost more than half their capacity. These are mostly small basins designed to catch dirt and debris.

The other option to remove sediment is dredging, but that requires draining the reservoir and using heavy equipment to excavate a volume of benthic muck that would fill a professional football stadium several times over.

“We all played in the sandbox as kids,” Pasternack told Circle of Blue. “But it’s really expensive to move dirt.”

Aquifers and Reservoirs

When policymakers and lobby groups talk about increasing storage they usually refer to these two categories. Reservoirs have the benefit of familiarity, while banking water underground prevents wasteful evaporation and is a buttress against land subsidence, which occurs when too much water is pumped from an aquifer and the ground deflates like an open balloon. Too much subsidence threatens to crack the canals that transport water across the state, as well as pipelines, roads, and the foundation for any high-speed rail lines that might cross the Central Valley.

–Lester Snow California Water Foundation

But if more aquifers are to be used as water banks, a position with broad support, then the rulebook will need to change as well, say top water policy experts.

Lester Snow, executive director of the California Water Foundation and a leader in negotiations for new groundwater regulations, asserts that clearer policies than those that currently exist are needed to protect a water user’s right to supplies stored underground. In many parts of the state, groundwater is loosely regulated and could be pilfered by a neighbor.

“If you store it, you want to protect it,” Snow told Circle of Blue. “You don’t want someone else to pump it out.”

New pipes and canals will be needed to move water to the most suitable aquifers. Some aquifers will need to be flushed of industrial or agricultural pollution before they can be used. Southern California’s aquifers hold the chemical legacy of World War II-era manufacturing, while the Central Valley soil is a sponge for poisonous nitrates and pesticides, both farming residues.

In addition, new collaborations between reservoir operators and groundwater managers will be required in order to maximize the value of the two systems, argues Ellen Hanak, a water analyst at the Public Policy Institute of California. To clear space in the reservoirs to hold flood flows, supplies could be transferred to a partner who operates a groundwater bank, Hanak said.

“It’s more work to set up,” she wrote in an email to Circle of Blue. “But it’s definitely something we’re going to need to do more of over time, especially as the snowpack shrinks with a warming climate.”

Reservoirs are the final piece in the storage puzzle. Four candidates will be considered for funding in the water bond: raising the height of Shasta and Los Vaqueros dams to increase their capacity; building Sites Reservoir in a dry canyon in western Sacramento Valley; and building Temperance Flat, a dam on the upper San Joaquin River northeast of Fresno.

Each of the options is being studied by the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which would be a partner in any construction plan.

For instance, the bureau released a feasibility study last month for the $US 2.6 billion Temperance Flat project. Contrary to nearly every dam, Temperance Flat’s primary justification is not water supply, but environmental restoration. The dam will increase supplies for cities and farmers by a piddling amount, but its main purpose is storing cold water to help revive fish habitat in the San Joaquin River.

Nearly all of its calculated benefits rely on the assumption that the dam will help reestablish salmon runs where none exists today.

The feasibility study assumes that U.S. taxpayers will bear 28 percent of the dam’s cost, while California taxpayers will pick up 45 percent, much of which could come from the water bond. The balance would be paid by urban water agencies and farmers with contracts for the reservoir’s water.

Sharon McHale, a Bureau of Reclamation project manager, told Circle of Blue that the dam would not be built without California’s financial support. “Not according to how we analyzed it,” she said.

A strong anti-dam push by groups who claim the reservoirs are too costly for too little benefit could mean that none of the projects is built. But California’s water system is so complex that no single project can fix it.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Raises all around!