Hanoi Sinks As It Grows

Unsustainable groundwater use is unsettling Vietnam’s capital.

HANOI, Vietnam — Like most burgeoning cities in Southeast Asia, Vietnam’s capital is crowded. Streets are full and bustling, and every inch of sidewalk is used as a restaurant, shop, or parking space. Hanoi’s economic boom is drawing 220,000 people a year from the countryside in search of a better life. Vietnam’s urbanisation rate of 4 percent is one of the highest in the region.

But while new buildings rise above the urban smog and street cacophony, Hanoi is sinking. And it’s sinking because it’s thirsty.

Hanoi’s population growth — twice as high as the national average — combined with a strong textile industry and a manufacturing sector that supplies the world with electronics and information technology are drawing down the region’s water reserves.

Aquifers are being pumped at an alarming rate, which threatens the city’s water supplies and its physical stability, experts say. Researchers forecast that by 2020 daily groundwater extraction will increase by 27 percent to 35 percent.

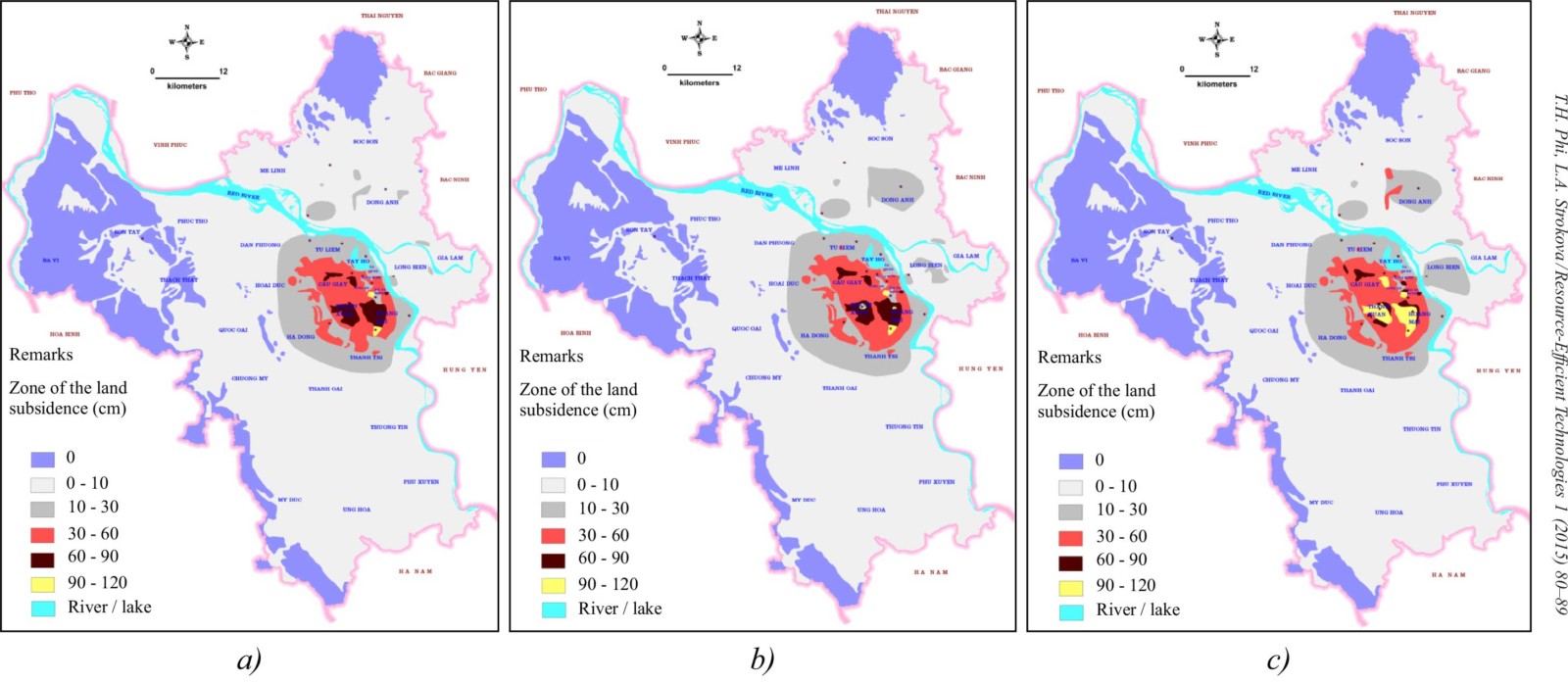

Excessive groundwater use has a harmful side effect. Pump too much water and the ground compacts, a process called subsidence that has damaged houses and buildings in the city. In little more than a decade, many areas in central Hanoi have subsided between 30 centimeters (1 foot) and 90 centimeters (3 feet), while the ground near Phap Van, a water supply station, sank by 104 centimeters (3.4 feet).

Prediction maps of the land subsidence in the Hanoi city caused by groundwater extraction in (a) 2013; (b) 2020; (c) 2030 from T.H. Phi, L.A. Strokova / Resource-Efficient Technologies 1 (2015)

As the city sinks, the effects are becoming more visible

In April, an apartment building in C1 Thang Cong district sank so much it had to be demolished and rebuilt.

“It was about time,” said a fruit vendor opposite the construction site. “The inhabitants were very concerned about security as they saw their homes becoming more and more unstable.” Another building at Quan Tho 1, in the Dong Da District, suffered a similar fate and was demolished last month.

To get a glimpse of Hanoi’s fate if nothing changes, one needs only to look at the world’s other thirsty cities that rely on groundwater: Mexico City, Shanghai, Bangkok, Tokyo, Dhaka, Jakarta, Manila, and others.

Relentless thirst cost Shanghai a delayed “water bill” of $US 2 billion between 2001 and 2019 due to economic losses from land subsidence. In Mexico City, streets open up and swallow citizens. Bangkok suffers from severe damage to private and public buildings, roads, pavements, sewers, and other underground infrastructure. Its final bill is yet to be determined.

With rapid population increase and rise in industrial water demand, Hanoi needs to act fast to avoid shackling its recently achieved economic progress.