Mobile Version – original story here

Stranded Assets: Water Stress Is Factor in Global Mining Slump

Floods, dam failures, public opposition batter big hard rock mines.

By Keith Schneider, Brett Walton, Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

NEW YORK – In a disclosure that came as no surprise in Peru, a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filing by Newmont Mining Corporation reported last February that the big Colorado-based mineral developer was indefinitely suspending work on its mammoth Conga gold mine in the Andes mountains near Cajamarca. Two months later the Goldman Environmental Foundation announced that one of the six winners of its annual Goldman Prize for environmental activism, among the world’s most prestigious public service awards, was Máxima Acuña, an Andes farmer and mine opposition leader.

The two events are closely tied together. In 2004, Newmont proposed to build the Conga mine not far from its existing Yanacocha copper and gold mine south of Cajamarca, which is the largest open pit gold mine in Latin America. Anticipating the sharp decline in Yanacocha’s mineral production, Newmont and its Peruvian mining partner, Minas Buenaventura, proposed to replace four natural lakes with a manmade reservoir at the Conga mine in order to reach what both companies said were rich mineral deposits.

MORE RESOURCES: Photojournal | Quest For Gold in Peru Met With Fierce Protests Over Water

The idea enraged Andes farmers who viewed the lakes and the water they held as vital and sacred. Máxima Acuña and her husband got involved because they own land on the Conga mine site that the developers sought to illegally seize with an eviction notice. She became a leader of the protest movement that spent more than a decade resisting Conga and eventually forced its indefinite closure.

The struggle between one of the world’s largest mining companies and a subsistence farmer defending her land and community’s water supply illustrates how strains over fresh water have become signal factors in the treacherous ecological, social, and economic geography that mine developers around the world must now traverse. On every continent where big hard rock mineral mines are proposed or are operating conflict over water availability and management is raising costs, increasing risks for lenders, driving tougher government oversight, and prompting much more aggressive civic opposition campaigns.

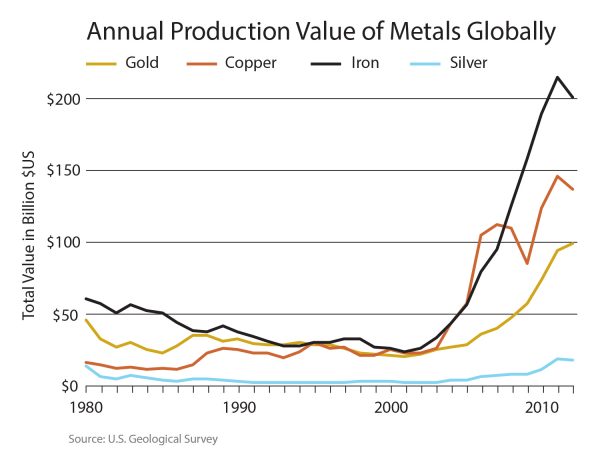

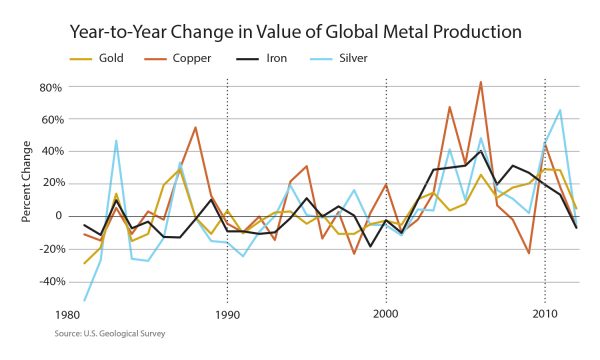

Along with China’s economic slowdown, which is weakening demand for minerals and metals, impediments caused by water-related stress have contributed to the deepest global slump in hardrock mine production and prices in decades. From a recent peak in 2014, mineral prices have tumbled precipitously, according to the World Bank. Iron prices are down 38 percent, copper prices slipped 22 percent, and platinum’s price is 30 percent lower. The top 40 mining companies experienced their first ever collective net loss in 2015, and their lowest return on capital, according to a report in January from Ernst & Young, the international accounting firm. Economic and operating hazards produced by floods, droughts, tailing dam failures, and opposition campaigns are leading to more scrutiny of financial risks by big lenders, abandonment of proposals for new mines, and mine closures. Water-related stress is a prominent reason that mining companies are unable to develop valuable mineral deposits around the world, in effect stranding them as undevelopable assets and sustaining billions of dollars in losses.

Peru, which ranks among the top three producers of copper, silver, tin, and zinc, and is the seventh largest gold producer, is a case in point. An estimated $US 30 billion in new mine projects are in limbo and may never be developed. “There are 150 social conflicts over mines in Peru right now,” Gonzalo Urbina Roca, an economist at the National Agrarian University, told a Columbia Water Center global workshop on mining-related water risks in September. “About 120 of those are related to environmental conflicts, and 90 of those are about water. There are 15 big mine and mine proposals stalled in Peru. That has never happened before.”

As in other nations, the Peru mining sector’s attention to water-related stress has evolved. In 1993, when Newmont and its Peruvian partner poured the first gold from the Yanacocha mine, business leaders and government officers celebrated the most significant foreign investment in Peru since the 1970s. Yanacocha spans nearly 1,600 square kilometers (600 square miles) across the summits of the Andes highlands 4,700m (15,500 feet) above sea level. Excavators and mining trucks at Yanacocha are capable of mining and hauling over 500,000 metric tons of ore a day. That is enough to open five deep pits, construct four towering terraced heaps of ore laden with gold, and operate three processing plants. The colossal mine, a geography of commanding industrial persistence, also is a permanent scar on the incomparably beautiful alpine grasslands high in the world’s second tallest mountain range.

Yanacocha also marked the end of the centuries-old era when global mining corporations could swoop into the world’s mineral-rich regions and operate with an unyielding sense of dominion over land, communities, and natural resources. Conflict between the mine and villagers that lived within sight was inevitable. As gold production steadily increased to 3.4 million ounces in 2004, and the open pits grew larger, so did resistance from farmers and highland residents, who complained about the intensity of the industrialization and changes in the quality of their water. In 2004, when Newmont proposed to drain four natural lakes for its new $5 US billion Conga mine not far away, neither the company nor its investors anticipated the fierce allegiance Andes farmers exhibited for their water supply. When the idea became public, Acuña participated in two weeks of occupation and roadblocks that forced Newmont to suspend the project.

Seven years later, in November 2011, when Newmont resumed construction on the Conga mine, she was involved in such ferocious battles at the mine entrance and in Cajamarca that Peru’s newly elected president, Ollanta Humala, declared a state of emergency. The resistance subsided after Newmont announced that it was again suspending work on the Conga mine.

Eight months later, though, protests over the Conga mine erupted again in Cajamarca and several Andes towns. Four people were killed in clashes with police in early July 2012 and at least 30 people were injured, according to news reports.

Mining Requires A Lot of Water

In Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, the mining industry withdraws an average of 70 cubic meters of fresh water to produce one metric ton of copper. As companies begin to process lower-grade ore bodies—meaning the rock contains less of the commodity being mined—more water is required to extract the same amount of product.

Water risks are translating into higher costs for mines. Companies spent approximately $US 12 billion on water management in 2013, which was three times the amount they spent in 2009, according to estimates by Moody’s Investors Service.

Chile has introduced legislation that would require mines using at least 150 liters of water per second to supplement with desalinated water sources. Desalination costs approximately $US 5 per cubic meter (1,000 liters) of water in Chile. Desalination also requires large amounts of energy—much of which is now produced by coal-fired power plants.

Uranium mines in Namibia are also facing the prospect of water shortages and increased costs for desalinated water. Three of the country’s mines, which collectively use about 10 million cubic meters of water annually, were forced to begin sourcing their water from a desalination plant after water supplies declined in a regional aquifer.

In a 2012 survey of 36 metals mining companies with a total market capitalization of $US 773 billion, the Carbon Disclosure Project found that 64 percent had experienced “detrimental water-related business impacts” in the past five years, and water stress was the most commonly reported risk. Further, 92 percent of the respondents identified water risks that they felt could create a “substantive change” to their operations, revenues, or expenditures within the next five years. In short, awareness of water risks is growing in the mining industry.

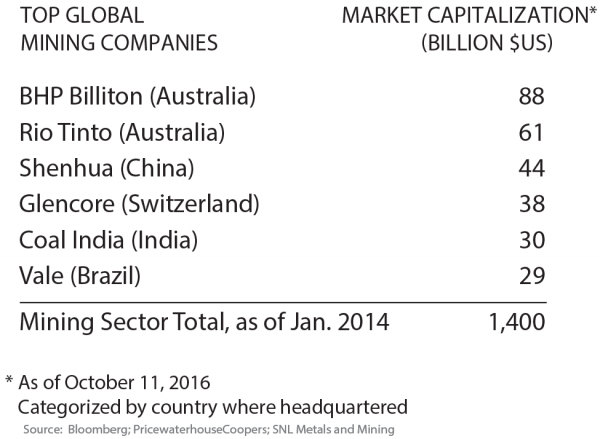

The operating rules for the global mining industry clearly had changed. In the four years since, conditions in the $US 1 trillion sector have become more financially difficult — and more socially dangerous. Leaders of groups opposing mines were assassinated in South Africa in March, and in the northern Andes last December.

Campesinos battled to block construction of this manmade reservoir at the Conga mine. The water storage site was meant to replace four natural lakes. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/CircleofBlue.org

Seeing the potential for conflict, other governments are taking a tougher stance in mining regulation. The new Philippines environmental secretary, Regina Lopez, has withdrawn operating permits for mines that pollute rivers and coastal zones, and has vowed to block big hard rock mines that threaten water quality, forests, and farmlands. In Mongolia’s South Gobi Desert, the confrontation over freshwater supplies between Rio Tinto and the region’s livestock herders prompted government regulators to require the world’s second-largest mining company to design and build a state-of-the-art water-conserving copper and gold mine. The Oyu Tolgoi mine, the largest industrial investment in Mongolia’s history, operates a closed loop production and processing system that recycles most of the 500 liters per second that the mine uses.

The more emphatic attention to water supply and pollution control has contributed to rising production costs. A 2013 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers found that production costs are growing faster than revenues. Among the crucial factors are community concerns about water pollution, supply, and access that are increasingly at the root of social turmoil roiling the global mining industry.

Water-related delays are expensive. For a mine project with capital expenditures between $US 3 billion and $US 5 billion, every week of delayed production costs the project $US 20 million, according to a 2014 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Moreover, by failing to address community concerns about water and other environmental and social issues, mining companies risk damage to their reputations and much tougher evaluation of project risks by lenders.

A Big Industry

Until the 21st century, mining companies measured success in profits, stock prices, and dividends. Mining nations measured success in jobs, investment, exports, growth, and revenue. The industrial mining industry— companies that are publicly traded or state-owned— employs roughly 2.5 million people worldwide. The formal gold mining industry alone employed nearly one-quarter of that, or 527,900 people in 2012.

By 2014, companies and nations added another measure of success or failure—the supply and quality of fresh water. One reason is that rural communities are much more sensitive to their water supplies than they were, and much better connected by smart phone and the Internet to information and global institutions to support their concerns.

A second reason is that limiting the risks to water and the environment from mining has been shown to add to economic and social performance. A 2014 study by the World Bank found that countries with strong mining industries and credible regulatory sectors, such as Botswana and Chile, have outperformed their non-mining neighbors in measures of human health and education.

Mining companies and their host countries also know that the contest for water will steadily grow more severe with the rise in global temperatures. The anticipated lifespan of a typical new mine is upwards of four to five decades. But by 2060, the water availability for mining projects will be radically diminished, say climate scientists, if the world does not reduce its carbon emissions. Such a risk now merits serious attention from the industry’s top executives.

Water Is Focus of Conflict

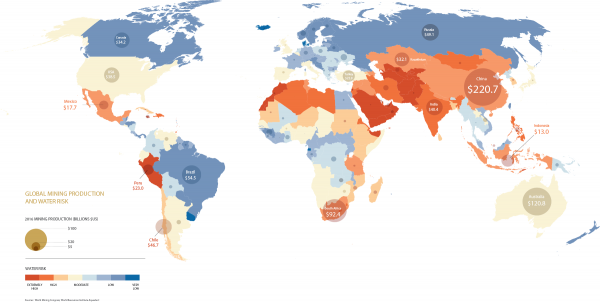

Community concerns about water pollution, supply, and access are increasingly at the root of economic and social turmoil in the global mining industry. Mining requires exceptionally large quantities of water. But droughts, floods, and pollution are more intense, and seasonal variability in water supplies has become much more erratic globally, weakening the industry’s water security. Fully 77 percent of the annual economic value of global mining, representing $US 770 billion in revenue, is in countries with moderate to extremely high water risk, according to assessments by the World Resource Institute.

The Conga mine is the second big project to close in South America in recent years over water stress. Community opposition to Barrick Gold’s Pascua Lama gold project on the Chile-Argentina border led to a series of delays, cost increases, and the indefinite abandonment of the project—one reason Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the company’s debt rating in 2013. The Chilean government fined Barrick $US 16 million for water management failures and other environmental problems at the project in May 2013, shares in the company dropped 5 percent after the announcement of the project’s delay in June 2013, and Barrick had spent $US 5 billion before shuttering Pascua Lama indefinitely in October 2013.

“This isn’t just about a set of technological processes and agreements,” said Nancy Langston, professor of environmental history at Michigan Technological University. “Responsibility and sustainability have to mean consultation with the communities. In the past, that has meant telling the community what is about to happen them. That’s not really consultation. Communities have to be a part of the decision-making process and have a right to veto.”

The threats are real. Out of 50 cases of mining conflict examined in the 2014 National Academy of Sciences study, half involved a project blockade, one-third led to at least one fatality, and about one-quarter led to the damage of property and eventual abandonment or suspension of the project. Two more high-profile projects that were suspended, closed, or rejected due to community conflict and water concerns in the past five years include the Toromocho mines in Peru, and the Rosia Montana mine in Romania.

“The mining sector has seen first-hand—the Newmont mine in Peru, for example—the tremendous amount of value that can be lost because of community opposition to expansion,” said Brooke Barton, director of the water program at Ceres, a sustainable development organization. “Closing that mine affected the company’s stock price and long-term financial health.”

The mining industry is getting the message. Barton wrote a report for Ceres in 2010, Murky Waters, that looked at the disclosure and transparency of eight industrial sectors. The mining industry ranked best for water risk disclosure and transparency.

Not all conflicts escalate to protests and blockades, and much depends on the underlying relationship between the companies and the communities, according to Rachel Davis, a fellow at the Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School and managing director of the non-profit business and human rights organization Shift.

“Many extractive projects involve impacts on local water supplies,” Davis said. “It’s a difference between—if there is a spill from a tailings dam and if something goes wrong—does the community trust the company to take action and respond or are they feeling like, ‘They didn’t listen to us when we had small problems, so now we need to make a big noise because there is a big problem’?”

Water Use in Peru’s Mines Foster Discord

Arguably no place in the world better reflects the economic and social turmoil caused by the confrontation between large-scale mining and risks to a region’s freshwater supply than Cajamarca, a city of 225,000 residents at the center of Peru’s northern Andes gold belt.

In 1993, following a decade of exploration and construction, Newmont Mining Corporation, in partnership with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and Minas Buenaventura, Peru’s largest gold mining company, opened the Yanacocha gold mine. In its two decades of operation, Yanacocha has produced more than 20 million ounces of gold worth more than $US 8 billion.

Yanacocha’s enormous mining pits and terraced mountains of ore established new global standards for size, technology, production, and profitability. The mine was planned in the 1980s during a decade of economic depression in Peru and opened in the 1990s in the midst of a civil war that claimed an estimated 70,000 lives. The mine is pitched on the dry Pacific side of the Andes, where water is scarce in the winter and the alpine lakes are essential for water storage.

Global Mining Data

Tailing Pond Disasters Pollute Water

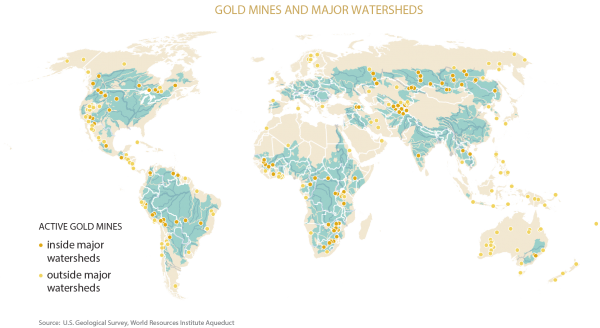

Mining is often the primary water user within a watershed and typically the biggest water polluter. Acid mine drainage is endemic in hard rock mining regions.

But mining practices that involve storing enormous quantities of liquefied wastes in ponds plugged by big tailings dams also have become a menace.

In November 2015, a tailings dam failed at an iron mine owned by BHP Bilton and Vale Mariana Brazil. About 60 million cubic meters of iron waste flowed into the Doce River. The environmental catastrophe killed 17 people and injured 16 more.

In August 2014, the tailings pond breached at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley copper and gold mine in British Columbia. Millions of gallons of contaminated water and slurry poured into Polley Lake.

The same month waste ponds at the Buena Vista del Cobre copper mine in the northern Mexican state of Sonora overflowed, spilling more than 40 million liters (10.5 million gallons) of water laden with heavy metals into local rivers.

Governments Respond to Water Risk

With mounting evidence of the economic, environmental, and social risks of water scarcity and pollution, national governments are enacting legislation to limit the damage and improve the governance of natural resources.

CHINA

In 1997, China enacted water-conservation legislation in the Yellow River Basin, which drains nine provinces in the country’s energy-rich and dry north. The law requires mines to recycle their process water and to prove that there is sufficient water in their regions to operate without compromising other water users.

INDIA

In 2010, India approved legislation to form the National Green Tribunal, a high-level court to hear and decide environmental cases. The Tribunal has issued stunning decisions, many of them focused on reducing damage to water supplies from mining. In 2013, the Tribunal issued a national order to shut down the sand mining industry so as to bring the industry into compliance with national water quality laws.

PERU

In 2011, Peru approved separate legislation that established a new agency to review environmental assessments and approve or reject authorizations for new mines and other industrial operations. The law was passed, and the 150-member SENACE agency was established specifically to withdraw the permitting authority from the Ministry of Energy and Mines and to restore credibility to the permitting process.

Production in Water Scarce Areas

More than a decade of periodic conflict and violence over water supplies began in 2000, when a truck that was transporting mercury from the mine spilled 150 kilograms of the toxic metal over a 40-kilometer stretch of road around the village of Choropampa. The accident poisoned thousands of people and prompted fierce protests. In 2004, Newmont proposed expanding Yanacocha to Cerro Quilish, a mountain that campesinos considered sacred and that sits alongside lakes that supply Cajamarca’s drinking water.

The proposal touched off years of occupation, roadblocks, and fierce demonstrations that prompted improvements in the management of water used to operate the Yanacocha mine, and eventually to suspension of the Conga mine.

The violence, and the company’s response to it, were closely watched worldwide by national governments, the mining industry, and environmental and human rights organizations. In India, mine managers noted their new devotion to water quality was a result of what they called “the Conga event.” In Mongolia, Rio Tinto executives said they designed state-of-the-art environmental protection and water-conservation measures at the Oyu Tolgoi copper mine to help quell civic criticism in the wake of the Conga protests.

How long the strife continues in Peru is anybody’s guess. But it isn’t getting better. Last December, Hitler Ananías Rojas Gonzales was killed in the Andes village of Yagén. According to Peru’s National Human Rights Coordinator, Rojas Gonzales’s death follows the unsolved murders of three other environmental leaders in the region, each fighting against the proposed construction of hydropower dams along the Rio Marañón, the headwaters of the Amazon River. One market for the dams is to supply power to Peruvian mines.

Less than a month ago, on September 18, Máxima Acuña and her husband were attacked and injured by the Yanacocha mine’s security guards. A video of the incident was recorded and posted to YouTube. The mining company claims it entered the property and removed Acuña’s crop field because it was land that belonged to the mine. “The company is acting within its property and in defense of their rights, and protecting the physical integrity and human rights of our workers and Chaupe family members, who do not have legal authorization to expand their activities inside Yanacocha’s property,” said the mine’s leaders in a statement. “So the action today responds to the strict compliance of the law.”

Mongabay, a California-based international environmental organization, reported that “Acuña suffered multiple contusions to her body and her clothes were ripped apart by the security guards’ shields.” The group joined other environmental and social justice organizations and “called for prompt action by the Peruvian state to protect the safety of Acuña’s family.”

The conflict near Cajamarca is driven by the same intractable ingredients, especially water security, that touch off mining disputes around the world. The closure of the Conga mine is a signal of a new order being established in the global mining industry. The balance of influence has shifted. Rural people are determined to have their say when billion-dollar enterprises want to use a region’s clear water to dig for valuable metals.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States (2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider