Water Bill Assistance for the Poor Hindered by State Laws

Restrictions on utilities result in weak aid programs, study finds.

The rising cost of repairing and replacing old water systems is contributing to an affordability problem across the country. Ambiguous state laws for water bill aid programs do not help the matter either, a report finds. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Beginning this year, poor residents in Raleigh, the capital of North Carolina, could apply for a $US 240 annual credit on their water and sewer bill. The City Council approved the utility’s first water bill aid program last December to ease the financial burden of a 10-year, $US 1.5 billion water system investment that caused rates to rise roughly 40 percent over five years.

There was a hitch in designing the program, though. Because of how state law is interpreted, the utility could not use its own money to fund the subsidies. Utility leaders had to appeal to the Council to use general fund revenues, which come from property and sales taxes, according to Ed Buchan, a water department analyst.

“Our own attorneys feel that we can’t provide direct assistance with ratepayer funds,” Buchan told Circle of Blue.

North Carolina law does not give utilities explicit authority to use the money they earn from water bills to provide aid to their poorest customers. As it turns out, the ambiguity in North Carolina is common across the country. State laws are an obstacle for utilities in nearly every state that seek to make water service more affordable for people at the economic bottom, according to a report published this week by the University of North Carolina’s Environmental Finance Center. Cautious interpretation of ambiguous laws prevents utilities from using ratepayer revenue, their largest source of income, to pay for customer assistance programs, or CAPs.

The legal uncertainty handcuffs attempts to offer a help, according to the report. “The vast majority of utility CAPs around the country tend to be rather small with limited ability to meet the needs of their at-risk, low-income customers,” the report states.

“We know of many cases” — particularly in North Carolina but across the country as well — “where a utility has limited the scope of their customer assistance program because they do not have the money if rates revenue is off limits,” Stacey Isaac Berahzer, the report’s lead author, told Circle of Blue.

Ambiguous Laws in Nearly Every State

Faced with utility bills that are rising in order to repair old pipes, America’s poor, from coast to coast, increasingly struggle to pay for water on top of food, medical, housing, and other expenses. There is no federal water bill assistance program, like there is for electric and heating service. Members of Congress from Great Lakes states that suffer from old infrastructure and high poverty rates have tried, without success, to pass legislation to that end.

There is a surprisingly large gap to fill. A 2016 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency review of 795 utilities, mostly those serving more than 100,000 people, found that more than seven out of 10 did not have a customer assistance program. California officials, seeing more than half of state residents getting water from a utility that does not offer bill aid, are designing the country’s first state-run program. The Philadelphia Water Department instituted, on July 1, the nation’s first water rate based on income.

The UNC Environmental Finance Center report is the most thorough examination to date of the maze of laws and regulations that govern customer assistance programs in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

UNC researchers compiled the report at the request of seven national water associations, which also funded the endeavor. The water associations wanted a guide to help their members — water and sewer agencies and water research organizations — better understand the legal limitations to CAPs and ways to sidestep them.

“We are not aware of any other resource that is as comprehensive,” Chris Hornback of the National Association of Clean Water Agencies, one of the organizations that sponsored the report, wrote in an email to Circle of Blue. “That’s one of the main reasons why all of the water groups involved in the project came together to do this. It was a gap in our knowledge that we knew was impacting our work in other areas.”

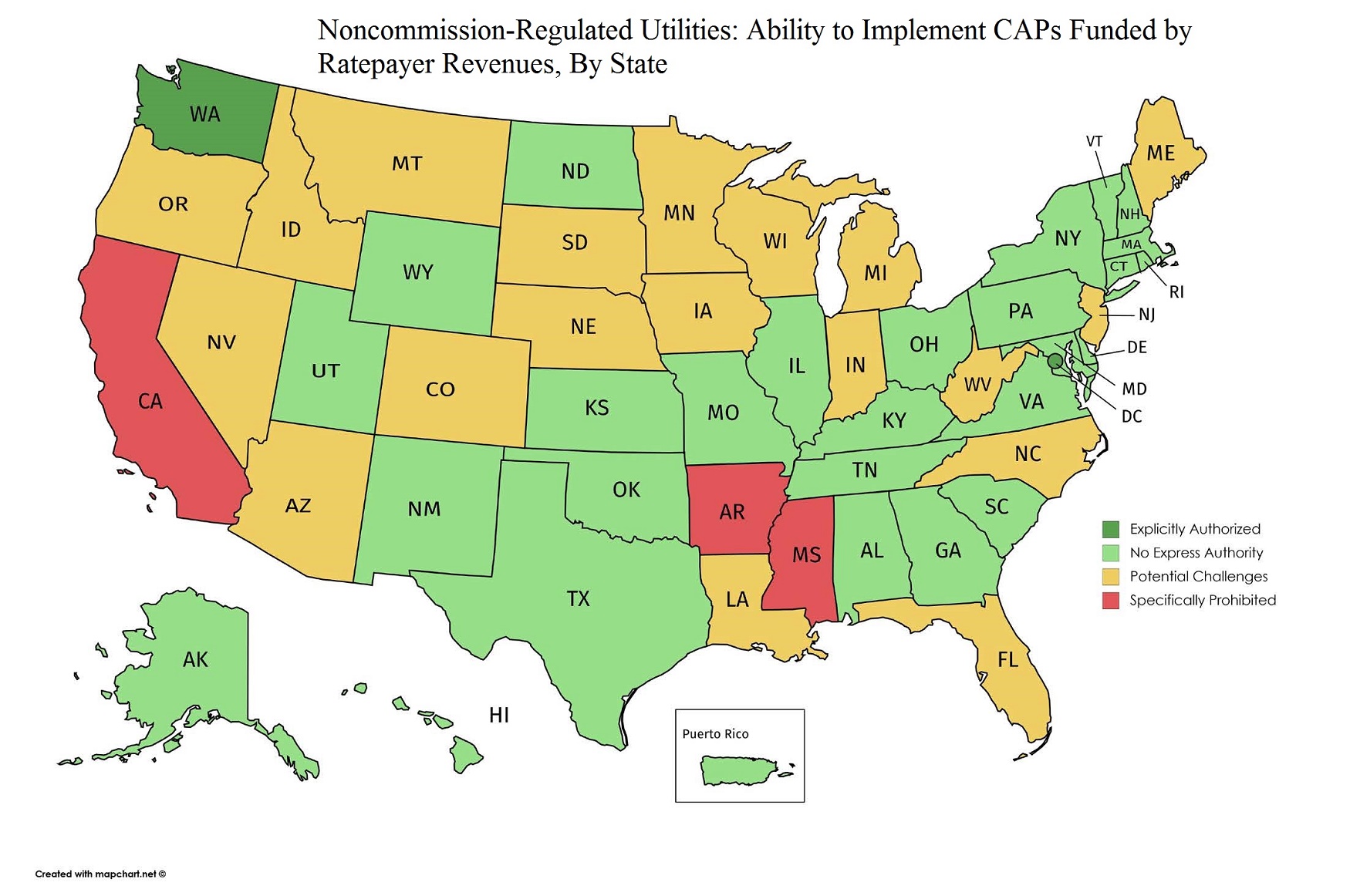

Each state sets its own rules for how water utilities can use money from rates. Many states have different regulations for public utilities and private-sector water companies. In some cases, notably California, public agencies are prohibited from using ratepayer funds for CAPs whereas private water companies are encouraged to do so.

Still other states have “home rule” laws in which utilities are allowed to set their own terms for establishing CAPs.

The number of states with clear legal language on the use of ratepayer funds for bill aid is tiny. Three states — Arkansas, California, and Mississippi — bar public water utilities from using ratepayer revenue for CAPs. Washington is the only state to allow it. (The report actually breaks down utilities into those that are regulated by a state commission and those that are not. But regulated utilities tend to be private while those not regulated by the state, public.) Most states, legally speaking, are in an ambiguous grey zone. If they run a CAP, utilities in these states might, instead of ratepayer revenue, use customer donations, grants from charities, or city tax revenue.

In few states are utilities explicitly allowed or prohibited from using revenue from rates for customer assistance programs. The map shows legal status for utilities, usually public agencies, not regulated by a state commission. Graphic courtesy of the UNC Environmental Finance Center

Within the grey zone, there are competing forces at play, Berahzer explained. On one side are utility lawyers, fastidious and cautious, whose close reading of the statues conclude that aid programs funded by revenues may violate the law and that the outcome of a lawsuit, if an aid program were to be implemented, would be uncertain. The utility may have to refund rates and pay court costs. For utilities, generally conservative institutions, this is an argument not to take action.

On the other side are social justice advocates, who testify at public hearings and march in the streets in support of residents whose water was shut off.

The laws that govern rate-setting do not provide much guidance, Berazher said. They use subjective words such as just, reasonable, and fair. “What does that mean? What is just?” she asked.

Rulings from lawsuits are usually a secondary guide. But case law in this area is scarce. The researchers could not find any direct examples in the United States of a lawsuit objecting to the use of water utility funds to pay for an affordability program. The closest proxies they could find were lawsuits against utilities for charging different rates for different customer classes and a lawsuit in Wisconsin against the city of Madison for charging higher rates on some groups in order to subsidize the replacement of lead service lines.

In the Madison case, a state appeals courts, in 2002, upheld a decision by state regulators to deny the city’s request to subsidize the replacement of lead lines for poor residents by charging higher rates on others.

Raleigh as Case Study

The factors that prompted Raleigh to establish its first CAP reflect a common development in the United States. Water use in Raleigh, as in many cities, is declining. Water use today is the same as a decade ago, Buchan said, even though the city grew by 110,000 people. With conservation came a drop in revenue. At the same time, long-due repairs to a water system largely built in the years following World War Two became necessary.

Bill assistance will reach only a fraction of the people in Raleigh who are eligible for it. The City Council authorized $US 200,000 for the first year of the program, which will provide $US 240 per year to 833 households. Buchan said that a needs assessment that the water department completed found that roughly 20,000 households, or 10 percent of customers in the city, would meet its eligibility standards.

“It was a sobering number,” Buchan said.

Berahzer hopes that utilities in states with ambiguous laws will learn from the report. It’s a tool, she said, that can help them respond in advance to a problem that shows no signs of abating.

“We only see the affordability problem getting worse,” she said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton