Lessons Learned? How Drought Has Shaped Water Policy in Georgia

Just as it was five years ago, a record-breaking drought is evident in Georgia. But has the state become more resilient through changes to water management policies?

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

On a warm weekend last month, the Georgia Canoeing Association canceled a trip on the Broad River, a free-flowing waterway in the state’s agricultural northeast region, and nearly canceled a trip on the Chattooga River in the state’s northwest corner.

If weather forecasts hold, watersports enthusiasts will not be the only ones affected by the uneven balance of water supply and demand. According to federal and state assessments, most of central Georgia is suffering from “extreme” or “exceptional” drought, the harshest categories. Even a normal amount of rainfall this time of year would be canceled out by evaporation and plant transpiration.

But this year is far from normal. Georgia’s latest deep drought is not only challenging the resolve of state residents, it is also testing measures that Georgia took since a devastating dry spell in 2007 — including new laws, a new planning process, and new money for water supply projects — that were designed to put the state on a path to a more secure water future.

What is not at all clear, though, is whether any of the new policy, planning, and supply initiatives are making a difference.

The state water plan, said Gil Rogers, an Atlanta-based attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, is not legally binding, which raises questions about how to enforce its provisions. The state, he said, lacks a clear plan for how to allocate water among users in times of low flows.

“The laws we have are not sufficient to address a really severe shortage,” Rogers told Circle of Blue.

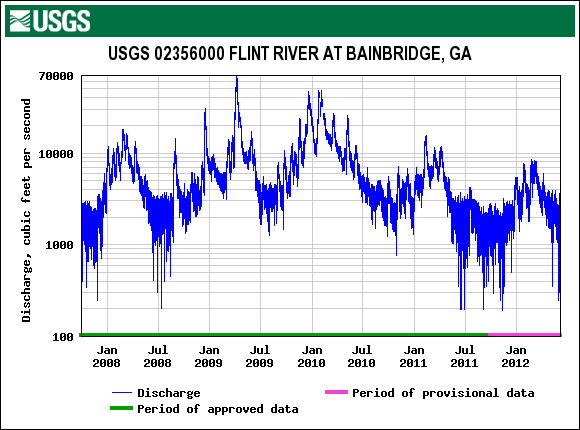

With summer just beginning, many rivers are already running below normal. The Georgia Climate Office reports that rainfall deficits from May 2011 to May 2012 are at record proportions in some areas. The town of Toccoa in Stephens County — the source of the Broad River where the canoeing trip was canceled — had a deficit of 63 centimeters (25 inches), the largest in 134 years of data collection. And even though Tropical Storm Beryl soaked the coast after making landfall on May 29, it did not reach far enough inland to affect the state’s parched interior.

Rather, drought conditions in central and northern Georgia are expected to “persist or intensify” through the end of August, according to computer modeling by the National Weather Service.

Still, low supply is not the only factor in Georgia’s water balance — farmers, cities, industries, and energy companies all need water. As the fastest-growing state in the Southeastern U.S., Georgia faces a recurrent challenge of ensuring that its water supply will meet the demands of a growing population, especially as dry periods occur more frequently.

“Shower Our State, Our Region, Our Nation with the Blessings of Water”

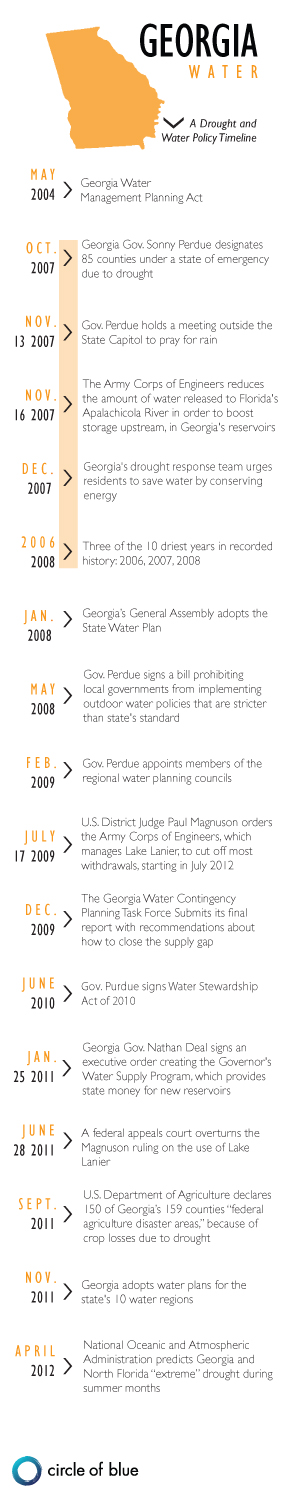

Georgia, of course, has been in this position before. In November 2007, during an autumn in which reservoirs fell to historic lows, in which outdoor water use was banned in many areas, and in which the state pleaded with President George W. Bush for an exemption to the Endangered Species Act so that it would not have to release water for animals at the expense of humans, Georgia’s Governor Sonny Perdue called a prayer meeting.

“I’m here today to appeal to you, and to all Georgians and all people who believe in the power of prayer, to ask God to shower our state, our region, our nation with the blessings of water,” Perdue told the crowd that day, in front of the state capitol in Atlanta.

The rains did eventually return, but not before bringing a stream of water legislation to a state assembly that, a decade ago, would not have even sent these bills to committee, said Rob McDowell, the environmental policy program director at the University of Georgia’s Vinson Institute of Government.

“I’ve been in Georgia for 20 years,” said McDowell, who has also worked in the state’s Environmental Protection Division, “and things have changed greatly. There’s been an improvement, if for no other reason than the change in public dialogue.”

The dialogue had started with orders from the top. Two months before the November prayer gathering, Governor Purdue had banned outdoor water use for the northern third of the state. A month later, he had ordered large water users to cut withdrawals by 10 percent. Then, in December, the state’s drought response team called for Georgians to conserve water by conserving energy, since the electric power sector accounts for more than half of all water withdrawals in that state.

As if to underscore the urgency, the press release encouraging energy conservation included this holiday-season tip for watering a live Christmas tree: “Take a bucket with you in the shower to capture excess water.”

The State Acts, But To What Effect?

Evaluations and legislation soon followed the mandates. In January 2008, the general assembly adopted the state’s first water plan, which was required by a bill that had been signed in 2004. The water plan asked for supply assessments, demand forecasts, and individual plans for the state’s 10 water regions. These regional plans were later adopted in November 2011.

In the middle of all this, however, a U.S. district judge issued a ruling in a decades-long legal tussle — known locally as the “tri-state water war” — between Alabama, Florida, and Georgia over water releases from a federally operated reservoir that is upstream of Atlanta. In July 2009, Judge Paul Magnuson ruled that water supply was not an intended purpose of Lake Lanier, the main source of water for metro Atlanta’s 5 million residents. Magnuson said that the region would have to cut its water withdrawals to 1970s levels within three years.

Though his decision has since been overturned, at the time, it was an effective ultimatum.

A task force looked at emergency supply options, and the legislature passed the Water Stewardship Act of 2010, which required water-efficient fixtures in new buildings, cooling towers for industrial facilities, and water audits for utilities. Many of the provisions come into effect on July 1 this year, so it is still too early to evaluate the act.

But the problem with these types of laws is how well they can be enforced, said Rogers, the attorney.

“It’s a step forward, on paper,” he told Circle of Blue, “but the provisions rely on a willingness to fund and enforce them and create the proper incentives. Georgia has a long way to go to incentivize conservation and efficiency.”

Critics point to three major actions to support this argument:

-

First, the state legislature passed a bill in 2008 that prohibits local jurisdictions from establishing outdoor water conservation policies that are stricter than the state standard. They can, however, apply to the state for a variance. (The Georgia Environmental Protection Division was unable to provide data on how many jurisdictions had done so.) But critics say this takes water planning out of local hands.

“Communities are put at a disadvantage if they want to chart their own water future,” Chris Manganiello, policy director for Georgia River Network, told Circle of Blue.

- Second, the state water plan does not have the force of law. Regional water councils can make conservation recommendations and include them in regional plans, but they cannot require that such actions be carried out. It is up to the utilities and the local governments, which are already somewhat constrained by state law pertaining to water conservation.

As part of the public comment process, the Georgia Water Coalition — comprised of 182 civic, environmental, and business organizations — wrote that the state water plan “should be clarified by future legislation that empowers regional councils to issue binding policies for water management.”

Moreover, the regional plans are based on political divisions rather than on watersheds, which eliminates the possibility of a comprehensive assessment. (For instance, Plant Bowen, a coal-fired power station northwest of Atlanta, withdraws water from the Coosa River Basin, but it is not a part of the Coosa-North Georgia planning region.)

-

And lastly, the state is placing its bets on water storage and inter-basin transfers in a time of tight budgets. One of the first actions that current Governor Nathan Deal took when he entered office in January 2011 was to sign an executive order creating the Governor’s Water Supply Program. The program provides low-interest loans and direct government support for new reservoirs and other supply-side projects.

Deal pledged to invest $US 300 million over four years, and no less than 14 reservoirs are on the drawing board. (The first round of applications is currently under review.) But this focus on building hardware is a common criticism of the Deal administration, which did not respond to interview requests for this article.

“We think things have gotten worse under Governor Deal,” said Sara Barczak, the safe energy director for the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. “It’s not just a matter of money, but a matter of will and the desire to protect long-term [Southeast] regional interests.”

So, while new reservoirs have priority and funding, other existing conservation programs lag. For example, in the lower Flint River Basin — one of the river systems that is part of the legal dispute with Alabama and Florida — Georgia has the authority to declare a drought and to pay farmers not to irrigate, in order to keep rivers flowing.

But despite overwhelming evidence, the state has not declared a drought on the lower Flint since 2002, and it will not declare one this year, either. The head of the Environmental Protection Division (EPD) told Georgia Public Broadcasting that there is no money to pay farmers and that the law is not effective.

“The act, in its present form, doesn’t help you achieve the management goal that it was designed to achieve,” said EPD director Jud Turner. “Therefore there’s no sense in declaring a quote/unquote ‘drought’ when it’s not going to have its intended effect to help you manage the resource.”

Gordon Rogers, the executive director of Flint Riverkeeper, told Circle of Blue that the engineers and the bureaucrats think the answer to the state’s water problems are more storage and transfers.

“The state will sink millions and billions in engineering fixes,” he said, “but it is not willing to put money in things that we know will save water.”

Bright Spots

Some areas have made progress. The water district in the metro-Atlanta area used 14 percent less water in 2011 than it did a decade ago. This is after water use outpaced population growth from 1985 to 2000.

Still, McDowell, the University of Georgia professor, says household use — especially for outdoor purposes — could see even more improvement.

“We can conserve a lot when necessary,” he said, pointing to the 20 percent reduction in metro Atlanta during the drought. “We can always endeavor to do more, but the amount of conservation overall has improved.”

In the energy sector, Georgia Power used better chemicals during a pilot study at Plant Bowen to make the cooling process more efficient, thus reducing the amount of water withdrawn from the Etowah River. The company used the pilot study as the basis for a joint water research center with the Electric Power Research Institute.

Other research projects seek to reduce the amount of water used in agriculture. For more than a decade, the Nature Conservancy’s Flint River Basin Project has brought together universities, water conservation districts, and farmers to explore water-saving technology and improved farming practices in one of the state’s top agricultural regions.

But in terms of broad and systemic action, groups are now trying to build on the foundation established by the state and regional plans.

“It’s not clear what else might happen with the state water planning process,” said Rogers, the Southern Environmental Law Center attorney. “But one positive that has come out of it is getting different users and stakeholders together. In a lot of areas, that had not happened before. We hope regional planning continues, if for no other reason than keeping face-to-face interactions alive.”

Alec Aja is an undergraduate student at Grand Valley State University and a Traverse City-based design intern for Circle of Blue. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!