Protests Over Water Safety, Bank Financing Rock Bangladesh Coal Plants

Rampal coal-fired generating station is defended by government, opposed by UN, and assailed by Bangladesh citizens.

The Rampal project in Bangladesh has spurred fierce public opposition since 2010, when residents learned of the proposed coal-fired power plant.

By Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

In 2010, when Bangladesh drew up its Power Sector Master Plan to develop thousands of new megawatts of coal-fired electricity, the government also bought 742 hectares (1,834 acres) of bottomland along the Passur River. At the time, the aggressive master plan and the flood-prone parcel, about 300 kilometers (190 miles) south of Dhaka, the capital, served what authorities considered sensible steps to achieve the same national goal – more power for industry and homes.

The master plan, mindful of Bangladesh’s strong textile-based export revenue, called for 30,000 megawatts of new generating capacity by 2030.

When the plan was written, some 70 million of Bangladesh’s 160 million residents had no access to electricity.

When the plan was written, some 70 million of Bangladesh’s 160 million residents had no access to electricity. The country’s GDP growth, more than 6 percent annually, was held back by electricity shortages. Bangladesh power stations, most fueled by natural gas, totaled roughly 10,000 megawatts of generating capacity in 2010, about the same amount of power delivered by Connecticut’s utility sector.

The Sundarbans mangrove forest and wetland is habitat for rare Bengal tigers.

Six years, though, turned out to be a treacherous and disruptive period of intense transition, not only in Bangladesh, but in any country that was intent on pursuing a national electrical development plan that relied on coal. The dramatic transformation that government authorities anticipated with the 20th century-style, coal-centered energy plan crashed into a wall of competing ecological and social impediments in the more crowded, resource-scarce, culturally activated 21st century.

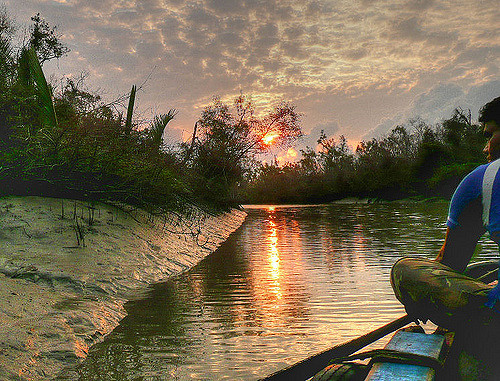

Public resistance to water pollution and disruption in water supplies form a sizable portion of the case that citizens make against coal projects in Bangladesh. The Rampal power plant, the development most besieged by protest, is condemned in and outside Bangladesh as a source of water and air pollution that will contaminate the Passur River and damage the internationally renowned Sundarbans. The coastal mangrove forest and wetland, so wild that it is habitat for 400 Bengal tigers, was declared a World Heritage Site in 1997 by the United Nations.

Clashes Over Coal

Work on Rampal and Bangladesh’s other new coal-fired plants has slowed dramatically and engulfed the country’s coal-centered energy strategy in waves of domestic opposition and international criticism. In April, four anti-coal campaigners were killed by police, and nearly 100 people and 11 police officers were injured during a ferocious protest against two Chinese-financed coal-fired plants in Gandamara, near Chittagong, the country’s second largest city.

Proposed coal plants in Bangladesh

Of the 19 coal-fired stations planned by Bangladesh, Rampal is the only project that has made any visible progress. Seven projects have been shelved, according to SourceWatch.org, a research group that tracks the industry globally. One of the projects, the 660-megawatt Orion coal-fired plant, was scheduled to be built near the Rampal project. Korean and Chinese financiers pulled out of two other large coal-fired projects. Japan pulled out last summer of a fourth coal-fired power plant.

Work on the Rampal project also has attracted international criticism. In September 2016, in an unusually strident report, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) condemned Bangladesh for siting the Rampal plant just upstream of the Sundarbans, and called for building the project in a safer place. Last spring thousands of Bangladesh anti-coal activists participated in a week-long, 400-kilometer (250 miles) protest march from Dhaka to Rampal, the latest of several marches since 2013. The Rampal project, financed by the India Export-Import Bank, has stirred clashes between opposition political parties and the governments of both Bangladesh and neighboring India.

The Rampal plant’s delays and rising construction costs are a factor in elevated electricity prices that will be uncompetitive in Bangladesh, according to a July study by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, an international research organization. And last year, South Asians for Human Rights, a watchdog group based in Sri Lanka, issued a fact-finding report that underscored weaknesses in the plant’s design, uncertainty about environmental compliance, improper land use, and trampled human rights.

“If the protests continue and intensify enough to halt the continuation of the Rampal project there is the risk to the financiers of the project being discontinued,” said Rohini Kamal, a research fellow at the Global Economic Governance Initiative at Boston University, in an email message to Circle of Blue. “Furthermore with increased global awareness around potential negative impacts, there could be reputational risk to the financiers as well. The negative impacts arise from 1) social concerns such as relocation of local populations and risk to the water bodies that people’s livelihoods depend on, and 2) from carbon emission emissions associated with coal plants and the potential loss of a valuable carbon sink, the Sundarbans.”

She added: “Related to this there is also a disaster risk component. Mangroves are considered a natural barrier protecting the lives and property of coastal communities from storms and cyclones, flooding, and coastal soil erosion. What this means for investors is that aside from social and environmental concerns there is also the added risk that the coal plant is exposed to in the face of climate change and weakened resilience to cyclones.”

Government Defense

Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed, a staunch supporter of the Rampal project, refuses to budge. In an August news conference, Sheikh Hasina said the plant will not harm the environment and accused critics of fostering a conspiracy to mislead the country. “I would be the first person to protest against the power plant if it would have the slightest impact on the Sundarban,” the prime minister said. “But there would not be any adverse affect on the Sundarban and environment after building the power plant. The plant will be equipped with the best technologies, the best quality coal will be imported from Indonesia, Australia, and South Africa. All modern technologies will be used at the power plant to curb any kind of pollution.”

Critics assert that the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest, is threatened by water and air pollution from the proposed Rampal coal-fired power plant, upstream on the Passur River.

She added: “An anti-development vested quarter has long been trying to create a negative attitude among people about the Rampal power plant project by making baseless, fabricated and imaginary statements and giving false information.”

The prime minister’s views were similar to a statement issued last year by the Bangladesh-India Friendship Power Company. The company is a joint 50:50 venture between the Bangladesh Power Development Board and the National Thermal Power Corporation, the Indian utility that is developing the Rampal plant. “The country’s overall development, apart from the power sector, will be hampered if the implementation of the project is delayed,” said company executives. “Various countries of the world have been giving thrust on using coal as an alternative source of fuel to generate electricity. In the USA 40 percent of electricity is generated from coal while in Germany it is 41 percent, in Japan it is 27 percent, in India it is 68 percent, in South Africa the percentage is 93, in Australia it is 78 percent, 33 percent in Malaysia and 79 percent in China. On the other hand, Bangladesh produces only 2.26 percent electricity from coal. So in order to ensure rapid economic growth we need to emphasize coal-based power plants.”

Investors Grow Wary

Public protests and concern about water-related stress and climate-changing emissions indicate, though, that Bangladesh authorities have not calmed the newest wave of opposition to Rampal– investment decisions on coal-fired power.

Public protests and concern about water-related stress and climate-changing emissions indicate, though, that Bangladesh authorities have not calmed the newest wave of opposition to Rampal

In October the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis took aim at the India Export-Import Bank, the government-managed investment group that has extended a $US 1.6 billion loan to build the Rampal plant. The IEEFA study found that 50 banks around the world – among them BlackRock, JPMorgan Chase, AIG, Prudential, Axis Bank, Crédit Agricole, HSBC, Bank of New York Mellon, UBS, and Credit Suisse – had purchased bonds to finance the India Export-Import Bank and were indirect investors in the Rampal plant. Many of these banks have issued sustainability guidelines that pledge not to invest in projects that are risks to the environment or social stability. This month Crédit Agricole announced it was ending all direct financing for coal power projects globally.

Rampal’s elevated electricity prices, expected to be well above norms in the Bangladesh market, could also potentially put the Indian Export-Import Bank’s loan, as well as investments made by the bank’s financiers, at risk from big losses.

“Nobody is against giving power for some of the poorest people in the world,” said Tim Buckley, the IEEFA director of energy finance studies in Australia and Asia. Buckley noted that Bangladesh has developed a safer alternative in solar power. Millions of solar-powered photovoltaic panels are being installed each year on rooftops across the country.

“Bangladesh has one of the world’s best programs for rooftop solar,” Buckley said in an interview with Circle of Blue. “So why is Bangladesh picking on a world heritage site, a big mangrove forest, the last refuge of the Bengal tiger? The Rampal plant is so fundamentally flawed in so many different ways.”

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider