Shenzhen’s New Path to Sustainability Is Crowded With Obstacles

A new and huge city focuses on getting cleaner.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

SHENZHEN, China-– Four numbers describe this colossal city’s unrestrained development.

In 1980, the year Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping established Shenzhen as China’s first special economic zone, opening its mercantile sectors to market capitalism and free trade principles, an attractive, tree-shaded commercial district known as Dongmen was home to 30,000 residents near the center of a metropolitan region of 300,000.

In 2015, 35 years later, Dongmen is a crowded commercial neighborhood of 300,000 residents at the edge of a city of 11 million and a metropolitan region that counts 18 million, China’s fourth largest. Though population growth has slowed a bit in recent years, Shenzhen’s expanding services and digital manufacturing sectors are riding the currency of expanding wealth and aspiration to a horizon of pure financial and cultural possibility.

This week, as negotiators in Paris consider a new development path away from carbon, China’s new determination to reduce its carbon emissions has produced skepticism about its resolve, and praise for apparently switching course. In few places are both responses more relevant than here in southeast China.

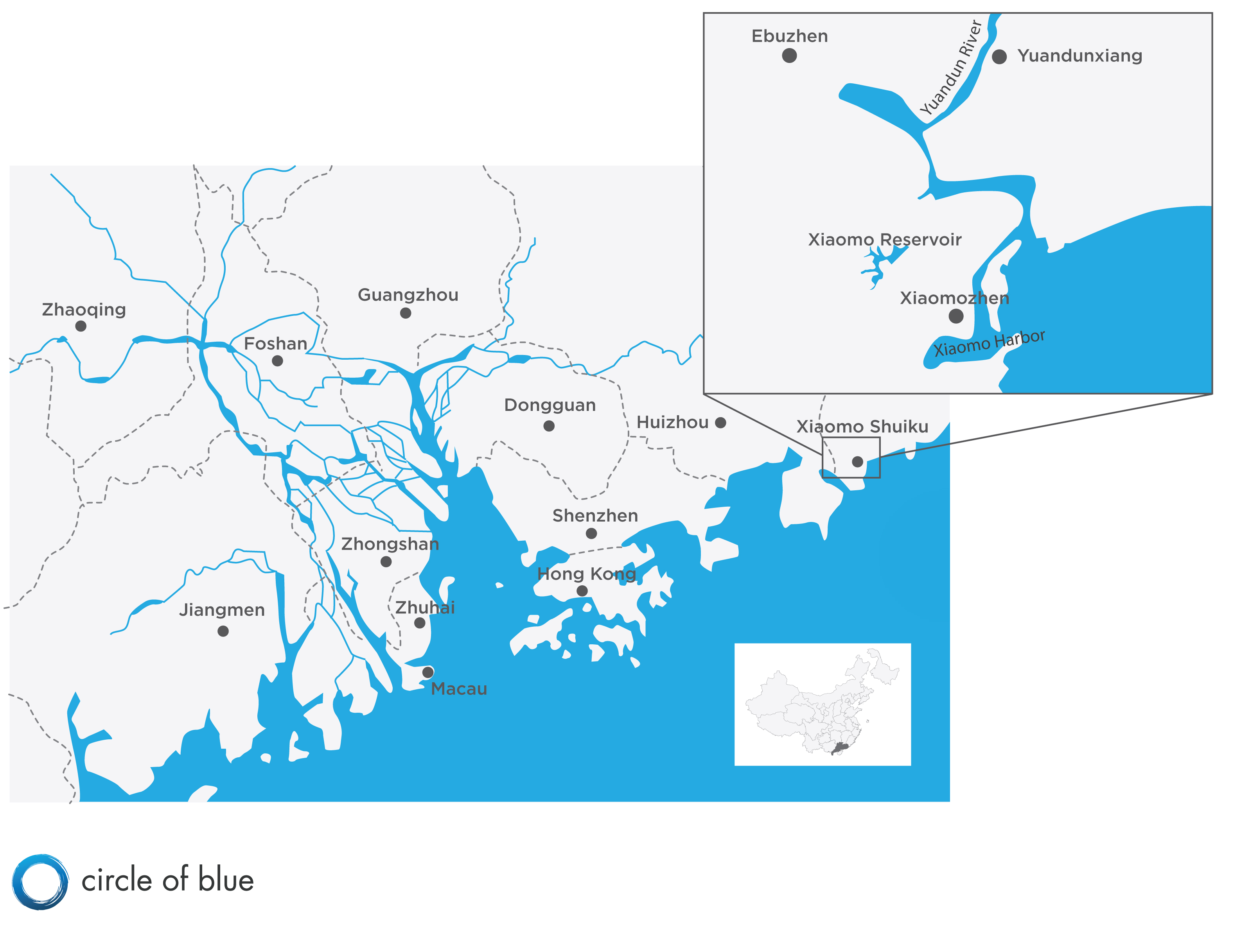

Shenzhen, and Guangzhou – its even bigger neighbor to the north – and seven more densely packed Pearl River Delta cities are seen by the Central government as one giant urban and economic region in the midst of a planned economic and ecological transition.

At the same time, though, Pearl River Delta cities are hampered by two hard-to-solve economic choke points: stifling air pollution and filthy water. Produced by a decades-long mismatch between economic goals and ecological neglect, the deteriorated condition of the environment now influences the Pearl River Delta’s capacity to attract trained professionals and entrepreneurs, who are essential to the pivot the region is making to cleaner finance, digital, information services, and computer manufacturing sectors.

“The big problem is the intensity of development,” said Xiaohong Chen, director of the Water Resources and Environment Center at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou. “It caused such damage to the environment. Management was so weak. Everything changed so quickly. Now we’re like a big experiment about what to do. It’s a large challenge here.”

As part of our Global Choke Point project the China Environment Forum, a program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and Circle of Blue are closely studying trends in energy, and water supply and use, in two Pacific port cities – Oakland and Shenzhen, China. The Choke Point: Cities project builds on five years of multimedia reporting and convening that examined the water-energy-food confrontations in China, Australia, the United States, India, Mongolia, and the Arabian Gulf.

Shenzhen and Oakland occupy opposite shores on the Pacific, and their basic profiles, no surprise, are shaped by attributes common and uncommon.

Unlike Oakland, which built a model sustainable development program in the United States that made ecological values a central premise of economic development, Shenzhen and provincial authorities were late in putting their focused attention on the burdens the city’s development put on its environment.

When they finally did, starting a decade ago, the technical complexities were more difficult than Shenzhen authorities anticipated. In 2006, for instance, the city started a four-year, $US 3.9 billion project to treat water pollution in 10 areas. But only modest improvements in water quality occurred, said Chunmiao Zheng, dean of the School of Environmental Science and Engineering at the South University of Science and Technology of China in Shenzhen. The city earlier this year launched what it hopes will be a more comprehensive and successful five-year, $US 12.6 billion water quality program to try again.

Guandong Province and Shenzhen also focused on air quality. Shenzhen is converting its buses to cleaner fuels. About 30,000 of what city authorities call “seriously polluting vehicles” were taken off the street in 2013, 10,000 more than in 2012, according to Shenzhen figures. Meanwhile, thousands of electric vehicles became operational, a silent armada of scooters, electric bicycles, cars, carts, buses, and trucks that whiz around every corner of the city.

And because the city says it now emphasizes energy efficiency, water conservation, and pollution prevention in its construction permitting program, Shenzhen is reducing energy demand and carbon emissions. By the end of 2013, according to the city’s website, cleaner buildings reduced fossil fuel consumption by 3.57 million metric tons, and carbon dioxide emissions by 9.23 million metric tons annually. That is equivalent to taking a 1,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant offline.

In 2009 Guandong province outlawed new coal-fired power plants in the Pearl River Delta and later ordered existing plants to convert to natural gas. Enforcement initially was spotty. But active civic protests against new coal-fired plants in and outside Shenzhen stiffened provincial resolve to make the 2009 order stick.

Guandong province last year also approved a $US 23 billion program to diversify and clear the air from the electrical generation industry by building new nuclear plants ($US 17.8 billion), wind power ($US 3.6 billion), and solar fields ($US 1.6 billion). It is not plain the diversification program will have much effect on emissions from Guandong’s existing 34 coal-fired plants outside the Pearl River District, which account for almost 51,000 megawatts of generating capacity and 76 percent of the province’s electricity.

Emissions from the province’s plants and countless coal-fired boilers mix with vehicle exhaust and make their way down the Pearl River in a visible brown cloud of pollution. More coal-fired plants are coming online, according to provincial figures, including 2,000 new megawatts of generating capacity from a coal-fired plant in coastal Xiaomo that is the site of a demonstration project to capture a small portion of the plant’s carbon emissions.

Shenzhen authorities like to boast that in the annual municipal accounting of sustainability in China, Shenzhen ranks high. A paper two years ago in the journal of the Chinese Academy of Sciences found that water and energy consumption, per unit of economic growth, peaked in Shenzhen during the middle of the century ‘s first decade and was dropping steadily. The cause was more energy efficient, water-conserving modern plants operating in the city by the 21st century, said Guoyo Qiu, a professor of environment and energy on the Shenzhen campus of Peking University.

Shenzhen also contends that by the standards of China, its air typically is among the best. Still, according to city data, last year concentrations of PM 2.5, a common measurement of sight-obscuring and lung-damaging dust, averaged nearly 40 micrograms per cubic meter, four times the health limit set by the World Health Organization. On a normal day, visitors can see the air they breathe in a contemporary, angular, high-rise city shrouded in smog.

The central challenge to the city’s cleanup is not money. Shenzhen’s treasury is full and the city’s political leaders, largely free to make decisions in a centralized governing system that has no citizen veto power, are accustomed to big investments in the public realm.

China’s air and water regulatory measures, as written and enacted, provide the necessary authority to act.

And China’s ability to marshal its innovative intelligence is keen. Shenzhen, for instance, freed a big drainage channel from concrete culverts and walls, cleared up the flow with treated water, and gave birth to a clean, free-flowing stream through its main city park.

Another of the measures to clean up and store scarce fresh water in Shenzhen is a project called “sponge city.” The idea incorporates three basic actions:

— Install roofs and rain gutters that channel water.

— Construct gardens, lawns, and surfaces that slow water down and allow water to be absorbed into the ground.

— Direct rainwater and surface runoff to underground retention ponds and treatment plants to clear drained water of pollutants.

The sponge city program, designed and managed by the city’s planning department, has installed the drainage and treatment program in two big residential developments and is promoting the idea in all of the city’s new construction.

If not money and ideas, what is the essential missing element of Shenzhen’s cleanup dilemma? According to environmental scientists and civic authorities, the core impediment is the capacity of city leaders and regulators to enforce restraints on polluters. Unlike the United States, Canada, and much of Europe, where enforcement is widely regarded as a strong civic need and value, in China directing companies to curtail pollution is viewed as either a threat to jobs and the economy, or distasteful interference. Chinese principles of privacy, and norms of appropriate government and personal behavior come into play.

Xiaohong Chen, of Sun Yat-sen University, has been involved for decades in assisting authorities in Guangzhou, upstream of Shenzhen, in pursuing a clean water urban strategy.

Four big stormwater retaining ponds were built as centerpieces of new parks and to allow sediment-laden runoff to settle. Wastewater treatment plants were constructed. Water-polluting companies were forced to close. One measure of the program’s success is the improved quality of the Pearl River, which flows through the center of the city and surrounding metro region of 20 million people. An annual celebration includes a swimming race across the Pearl.

But, Chen explained, many of the companies closed by the city moved their plants upriver into the watershed. Local and provincial authorities upstream, he said, allow the new plants to operate without contemporary water pollution prevention equipment. Progress in cleaning up the Pearl River is in danger of being reversed.

“The factory always wants to make money,” Chen said. “Local governments can’t measure every time, monitor every outlet. We have too many small workshops.”

Another of the water scientists that Shenzhen turned to for help is Chunmiao Zheng, a 53-year-old groundwater modeling expert who spent half his life in the United States, much if it at the University of Alabama where he was a professor in the Department of Geological Sciences. After returning to China for a brief stint at Peking University, Zheng was recruited earlier this year to lead the School of Environmental Science and Engineering at Shenzhen’s South University of Science and Technology of China, which opened in 2011.

Among his primary assignments, along with recruiting top researchers and building his department, is helping municipal authorities execute a five-year $US 12.6 billion water cleanup project, its second water quality campaign in a decade. This time, Zheng counsels, Shenzhen needs to take a holistic, comprehensive approach that, like a speeding train, charges directly at the seminal problem: curtailing pollution at its source.

That means treating all discharges from manufacturing plants, residences, and commercial centers. Removing sediments and contaminants from stormwater. Cleaning up pollution sources that make the water in almost all of Shenzhen’s streams unusable for any purpose. The region’s groundwater, which is seriously contaminated, needs remediation. Zheng counsels the city to rebuild wastewater transport networks so they do not leak, and so that sewage and stormwater flow in separate pipes.

“So far as I know, nothing like this project has been done in China,” said Zheng. “Shenzhen will try to become a leader in water quality improvement on a massive scale.”

The assault of bad air and worse water in Shenzhen are the perfect distillation of serious risks to health and the economy fostered by unrestrained development. But in a city where tall towers and speedy metros are also the negotiable currency of progress, cleaning up the environment in this region of China seems readily possible. Given the Pearl River Delta’s 35-year record of evolving to meet new market conditions, it is a good idea to consider Shenzhen’s cleanup task dismaying, but far from impossible.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!