Treaty Rights Acknowledged For First Time in Oil Pipeline’s Controversial History

Michigan’s Indigenous communities hold long-standing legal rights to protect lands and waters.

By Elena Bruess, Circle of Blue – March 12, 2021

On any given day, Jacques LeBlanc Jr. spends as many as 14 hours on the water catching whitefish. Out on his boat by the time the sun breaks the horizon over the Great Lakes, he moves between Michigan, Huron, and Superior for the best spots. In this part of northern Michigan, at the eastern end of the Upper Peninsula, fishing is a staple of LeBlanc’s Bay Mills Indian Community, one of the Sault Ste. Marie bands of Chippewa.

Fishing on the Great Lakes is no easy task. It is threatened by the changing climate, disturbed by invasive species, and overrun by unruly weather to daily operation costs. But just south of LeBlanc’s tribal community lies another impediment that endangers his way of life. It is Line 5, the twin petroleum pipelines that run underwater for five miles across the Straits of Mackinac.

Though the pipelines are hidden beneath 100 feet of water, Michigan has conducted encompassing state reviews, finding that the owner, the Canadian company Enbridge Energy, has a history of safety violations that put the Great Lakes at risk. Because of this, Line 5 is the source of the most significant legal and political confrontation over environmental safety and energy transport ever in Michigan.

Indigenous communities like LeBlanc’s have long contested Line 5, but only recently has the state addressed this. Last November, Gov. Whitmer revoked the easement that allows the pipelines to operate, and ordered Enbridge to halt oil transport by May this year. Cited in the revocation, for the first time in the history of Line 5, Michigan’s administration officially acknowledged nearly 200-year-old Indigenous Chippewa and Ottawa treaty rights as one of the reasons to shut down the pipeline project and protect Great Lakes ecology and fisheries.

The 1836 Treaty of Washington:

In 1836, the Indigenous Anishinaabe people — Chippewa and Ottawa peoples — signed the Treaty of Washington and ceded nearly 14 million acres of territory to the settlers, or 40% of Michigan state. This land included the northwest area of the Lower Peninsula and the eastern portion of the Upper Peninsula. In return for signing, the treaty guaranteed the Anishinaabe peoples reservation lands and forever access to all natural resources, including fishing and hunting rights. After signing, congress changed the terms of the agreement, only guaranteeing these rights for five years before the Chippewa and Ottawa peoples were to be forced out of Michigan. The communities fought these terms and reaffirmed their claims to the land in the 1855 Treaty of Detroit. Here are the borders of the Treaty of Washington, along with the CORA tribes, or the Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority. These tribes are all within the 1836 treaty and work to protect the rights guaranteed to them nearly 200 years ago. Map © Cayla Anderson / Circle of Blue

A Bay Mills fisherman works his net on the lake. © Photo courtesy of Whitney Gravelle

“The Ojibwe [Chippewa] in Michigan signed five different treaties throughout history, but the really big treaty that everyone talks about is the 1836 Treaty of Washington,” says Whitney Gravelle, in-house counsel and tribal attorney for the Bay Mills Indian Community. “We ceded almost 14 million acres of territory, but in return we asked for certain rights, the most important being our continued relationship with the water and our right to fish and provide food for our families.”

The 1836 Treaty of Washington’s boundaries cover the eastern part of the Upper Peninsula and a western chunk of northern Michigan, running along Lake Michigan to Thunder Bay River. The area encompasses not only the Bay Mills Indian Community, but the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, and the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. The five tribes form CORA, the Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority, an inter-tribal management body for 1836 treaty rights.

The treaty’s thirteenth and final article reserves the right for the Indigenous Anishinaabe people of Michigan (meaning the Ottawa and Chippewa peoples) to hunt and fish on any ceded land and water. It’s a right that Line 5 jeopardizes.

University of Michigan researchers used computer simulations to model the consequences of a Line 5 rupture. Their results, published in 2016, found that the turbulent Straits are the worst place in the Great Lakes for an oil spill. Depending on the size of the spill and weather conditions, oil would spread across the shores of Michigan and Ontario.

For this reason and others, a spill in the Great Lakes could have an irreversible impact on the tribe’s way of life, according to Gravelle. It wouldn’t just threaten the fishery. It would also shake the Anishinaabe role of protecting the water, the land, and the future of these resources, which, according to the treaty, must be guaranteed for centuries to come.

“In this context, [the inclusion] is a big deal. It’s an acknowledgment of an implied right to a homeland that Indigenous people negotiated in the 1836 treaty,” says Matthew L.M. Fletcher, the director of the Indigenous Law and Policy Center and a member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. “Fifty years ago, in the state of Michigan, the government would have told everyone the treaties are meaningless, that they had been aggregated by history. Now they’re in much better shape.”

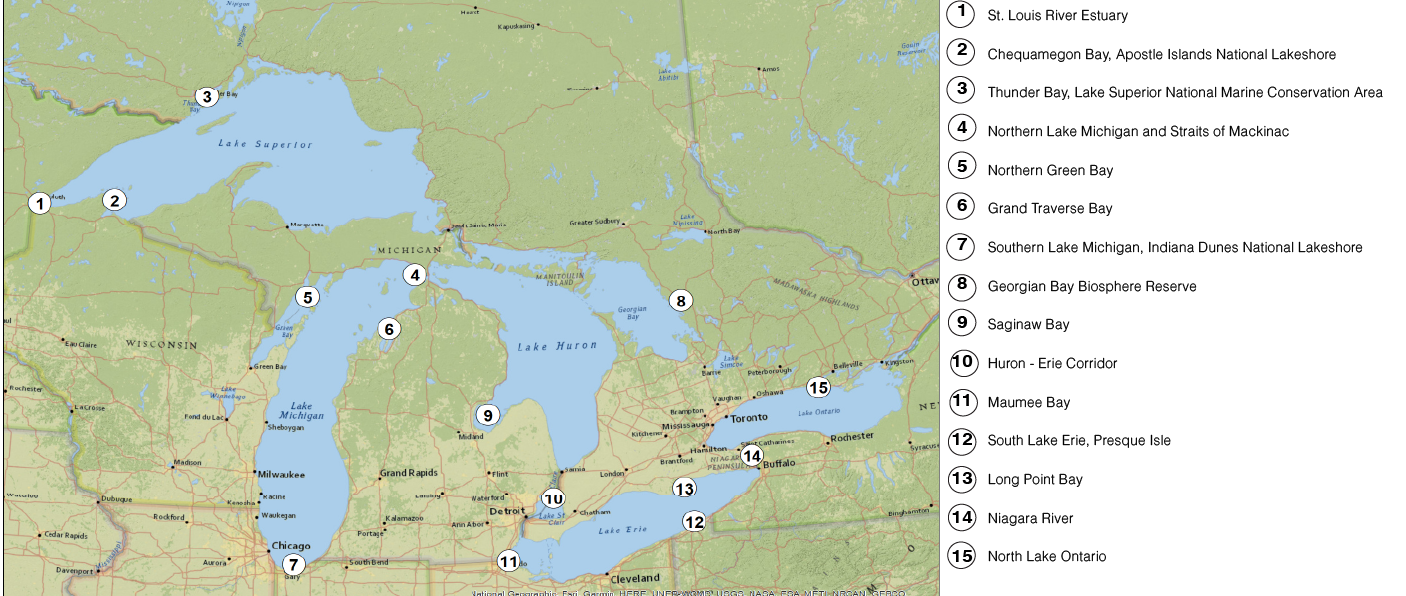

Great Lakes Areas of Vulnerability to Crude Oil Spills:

In 2018, the International Joint Commission’s Great Lakes Science Advisory Board published a report that helped define the damage possible if there was a crude oil pipeline spill. Researchers used ecological impact data from ocean spills, such as the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, and two freshwater spills, including the Kalamazoo River crude oil spill in 2010. The commission found that all levels of the aquatic ecosystem would be affected by a crude oil spill, along with drinking water for many of the 40 million people who depend on the Great Lakes. This map highlights the 15 locations around the lakes that have the most vulnerability to an oil spill. Researchers analyzed the amount and type of oil spilled, the exposure, sensitivity, and the resiliency the area has when confronted with crude oil. Many of the habitats are home to wild rice, lake sturgeon and trout populations, and coastal wetlands, all of which are ecologically vulnerable to a spill. Map by Cayla Anderson © Cayla Anderson / Circle of Blue

In 1836, the Indigenous Anishinaabe people — Chippewa and Ottawa peoples — signed the Treaty of Washington and ceded nearly 14 million acres of territory to the settlers, or 40% of the state of Michigan. n return for signing, the treaty guaranteed the Anishinaabe peoples reservation lands and forever access to all natural resources, including fishing and hunting rights. © Photo by Laura Herd / Circle of Blue

In 1836, the Indigenous Anishinaabe people — Chippewa and Ottawa peoples — signed the Treaty of Washington and ceded nearly 14 million acres of territory to the settlers, or 40% of the state of Michigan. In return for signing, the treaty guaranteed the Anishinaabe peoples reservation lands and forever access to all natural resources, including fishing and hunting rights. © Photo by Laura Herd / Circle of Blue

An Identity at Risk

Jacques LeBlanc Jr. grew up fishing, learning from his father until he began his own business nearly a decade ago. His grandfather (Gravelle’s as well) is Albert “Big Abe” LeBlanc, a tribal legend who back in 1978 fought and won in federal court for the reaffirmation of Chippewa and Ottawa treaty fishing rights in the state of Michigan. Now, more than four decades since Big Abe stood in court, fishing is once again in peril.

A pipeline leak in the Straits, the segment of water flowing between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, could spill thousands of gallons of crude oil into either lake, with the potential to damage hundreds of miles of shoreline, according to the governor’s Notice of Revocation and Termination of the Easement. Spilled oil would cause short-term and long-term damage to the ecosystem and varieties of fish in the Great Lakes. Because of that, a disaster also would pose a serious cultural, economic, and ecological threat to Michigan tribes, including to treaty-protected rights.

A woman bends to touch the water at the Straits of Mackinac. © Photo by Whitney Gravelle

For the Bay Mills Indian Community, the importance of water goes back thousands of years. Their identity is connected to the water and the land. When the Anishnaabe first traveled to the area that is now Michigan, they were advised by a medicine man that they must go to where food grows on water. They moved west until they found manoomin, or native wild rice, on water and settled down. According to the Ojibwe creation story, North America is Turtle Island. At the center, at the turtle’s heart, are the Great Lakes, where the Anishnaabe found home.

The story is also directly tied to the Straits of Mackinac. Mackinac is derived from the Ojibwe word mikinaak, meaning turtle. Fort Michilimackinac, situated on the south end of the Straits, translates in Ojibwe to ‘the place of the great turtle.’

For LeBlanc, the water has always been attached to fishing as well. When he arrives at a new area to fish, he will ask that the water take care of him and keep him safe, and that the lake provide enough for him to maintain his life. LeBlanc says he will never take more than he needs, never waste anything that he catches. If his gill net pulls anything other than a whitefish, he throws it back.

“Back when the population was smaller, in the 60s and 70s, around half of adult males in the tribe were fishermen,” LeBlanc recalled. “We’ve always been drawn to that because of our ancestral ties, the water, the fisheries, that’s how we sustained our way of life. The cultural component runs very deep.”

Since LeBlanc began fishing in his youth, he says the lakes have changed drastically. Fish stocks have been depleted, invasive species have moved in, and winters and water levels have been unstable.

Line 5 also has been one of the biggest threats to his home and the water for years, particularly with Enbridge’s recent history of close calls and violations. In 2019, a ship anchor struck and dented the pipeline, and independent inspections found the pipeline’s metal surface is corroding. Enbridge’s operations record in Michigan is weak. In 2010, an Enbridge pipeline in southern Michigan ruptured and poured nearly 1 million gallons of toxic oil into the Kalamazoo River. It was the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history and Enbridge spent over $1.2 billion for cleanup, plus nearly $200 million in fines and penalties. Since the governor’s revocation of the easement, Enbridge has filed countersuits, asserts Line 5 is safe, and vows to keep the line operating.

Scientific data gathered from the International Joint Commission in 2018 found that 15 spots around the Great Lakes such as Grand Traverse Bay, Thunder Bay, and the St. Louis River estuary would be particularly vulnerable to an oil spill, affecting wild rice growth, lake sturgeon and trout spawning, and coastal wetlands. Among other issues, oil is toxic to certain birds, decreases abundance in lake-bottom organisms, and can cause deformities and developmental delays in lake fish.

“What [Line 5] could do to Lake Michigan and Lake Huron down there would all but close that entire resource for fishermen,” says LeBlanc. “Then depending how they could manage oil runoff into Lake Superior, it could certainly make its way up here and have a huge impact. But even if Superior managed to stay filtered and clean, the pressures of all the fishermen having one resource to fish from would have a catastrophic impact as well.”

Looking out at the Aurora Borealis and comet NEOWISE from the shores of Whitefish Point. Photo © Marybeth Kiczenski

Looking out at the Aurora Borealis and comet NEOWISE from the shores of Whitefish Point. The 1836 treaty reserves the right for the Indigenous Anishinaabe people of Michigan (meaning the Ottawa and Chippewa peoples) to hunt and fish on any ceded land and water. Photo © Marybeth Kiczenski

Looking Ahead

Including the treaty in the easement revocation may also have implications for other state environmental policy issues such as mining, though it’s immensely complicated. Michigan historically did not talk to the Indigenous communities, Fletcher says. And recent consultations, while a good start, are still inadequate to the tribes. The current administration and the tribes have some of the same interests, including clean water in the Great Lakes, but state politics play a big factor as well.

“We all want a good habitat here, but let’s be frank, the amount of pressure the Whitmer administration is under is absolutely enormous,” Fletcher says. “It’s amazing that they did this, but if confronted with enough political pressure or interest in economic development, it’s hard for me to believe it’ll be a guarantee going forward.”

As for Line 5, it’s really just a matter of when it’ll be gone, according to Fletcher. This way of generating energy is on the way out, but it’s going to be a fight.

LeBlanc is also hopeful. Even as Enbridge refuses to comply with the easement revocation from the Whitmer administration, he believes in the Bay Mills team and other Indigenous communities working on the issue. Just like his grandfather in court all those years ago, the 1836 Treaty of Washington is proving to be an important lever.

The Bay Mills Indian Community knows what it’s like to lose a resource, Gravelle says. They don’t want anyone else to lose it either.

“There’s still a lot of work to do to ensure the Great Lakes are around for the next seven generations,” she says. “We finally feel like we have people behind our back and we’re ready to move forward.”

Featured Image: The sun sets over Lake Superior as Bay Mills fishermen work to catch their day’s worth of whitefish. © Photo by Whitney Gravelle

Elena Bruess writes on the intersection of environment, health, and human rights for Circle of Blue and covers international conflict and water for Circle of Blue’s HotSpots H2O.