California Drought Prompts Personal Adjustments

This drought is different, people say — much different.

Californians lit up Facebook on Saturday with pictures of the deep snow that fell in Yosemite National Park. In Los Angeles, residents shared smartphone shots of raindrops on their windshields. The skies released a little moisture on parts of California last week, though not enough to alter the state’s dire water deficit. Public reaction to the storms, however, reflects a growing dread among citizens that this drought, more so than previous dry periods, is leading the Golden State into uncharted terrain.

It is big. Really big.

“The Yosemite snow was all over Facebook this morning,” said Ruth Leach-Stevens, a clinical nurse manager who lives in San Francisco and is a fifth generation Californian raised in Amador County, in the Sierra foothills. “It gives you an idea of how anxious people are and happy they can be with some new snow. There’s hope.”

California’s four-year-old drought, said by scientists to be the deepest in recorded history, plays out in multiple dimensions. At the macro-level, where the acute water shortage affects California’s cities, its mammoth farm sector, and its web of industrial and high-tech industries, state water managers are issuing first-of-their kind water restrictions and deciding how to spend billions of dollars in bonds to limit the pain.

At the micro-level, in the homes of California’s nearly 39 million residents, and in the offices and businesses where they work, the moisture shortage is producing innumerable personal responses.

I lived in Sacramento for a few years in the early 1980s, and worked in San Francisco for a couple more years in 2008 and 2009. I remain in contact with dear friends and colleagues who live in California. I called a few of them to see how the drought was influencing their lives. By no means does this group of skilled and successful professionals represent an exhaustive or representative sample of Californians. It was, though, interesting and enlightening.

“There’s been times when it’s been dry. But nothing like this,” said Judith Fox, a biomedical scientist in San Francisco who has lived in California since 1991. “This is like insane. It is changing, maybe too slowly, how people live. You can’t really put your head in the sand anymore.”

Others have stories of more drastic responses.

“I’m freaked out about it, quite simply. I haven’t watered my garden in who knows how long,” said Susan Alexander, a communications consultant in San Francisco. “People talk about it, in the context of the awful skiing, their gardens, the news — whatever. It does come up in conversation. I had a friend in Santa Barbara who moved to Portland to escape it. That’s how freaked out she is.”

Thinking Differently about Water

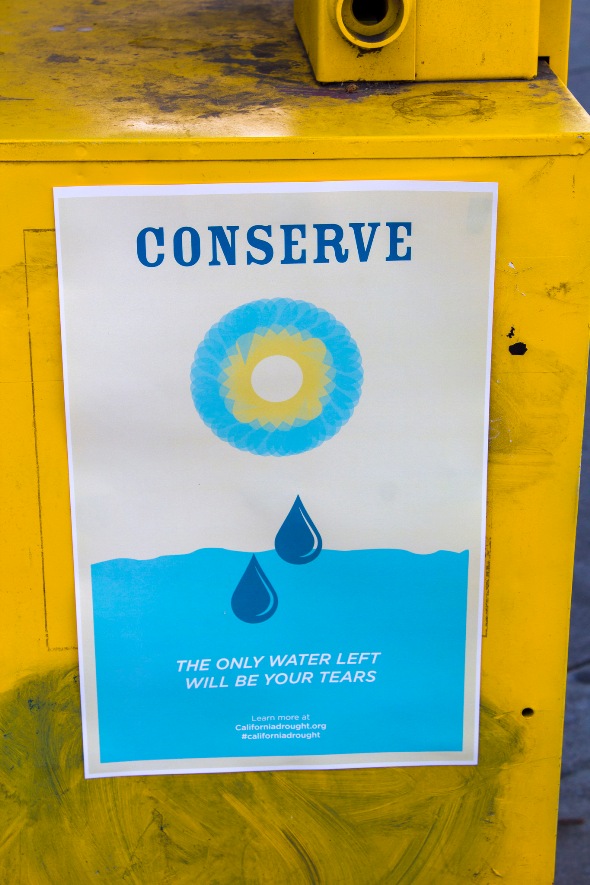

Like almost all of the people I interviewed, Fox and Alexander long ago made the changes in bathroom, kitchen, and garden practices to do their part to conserve water. Shorter showers. Care in washing dishes. Leach-Stevens’ neighbor collects the grey water from her shower in a bucket and uses it to water a small garden.

“I stopped watering my gardens,” Fox told me. “I’ll probably take a lot of my plants out and replace them with succulents. We’ve been thinking about not wasting water for a long time here. But it’s different. The car wash down the street is doing more conservation. People talk about it. It’s kind of permeated everything.”

Several friends said the drought had prompted them to be surprisingly vigilant, at home and at work, about conserving water.

“I’m a total eco-cop anyway,” said Alexander. “This water thing. I’m yelling at my daughter to stop flushing the toilet! I know everything I’m doing is a drop in the ocean. I still feel driven to do it.”

Heidi Pickman, who lives in Oakland and works in San Francisco as the director of communications for the California Association For Micro Enterprise Opportunity, surprised herself not long ago. “I was in the ladies room one morning and there was a woman there doing her hair and running the water full blast. I’m totally yelling at her.

“’Don’t you know there’s a drought? What are you doing?’ It was one of those instinctual things that came out of me. ‘Why are you not thinking about this? Why is this not in your consciousness?’

“She looked at me. I think she shut the water off. She looked at me like, oh my God.”

Californians in the state’s northern cities often accuse southern Californians of being less intent about conserving water, less resolved to collaborate in a shared response. Though my sampling is limited, I didn’t find that to be the case among those I interviewed.

Jeff Zucker, a photographer in the Venice Beach section of Los Angeles, said he and his family made changes that help make a small difference in overall water use. “They’re small but we thought about them,” Zucker said. “I turned the sprinkler off. I don’t hose the pathway to the front door like I used to. I use a broom. That’s minor, but its’ an effort to be conscious. We’re told 80 percent of all water used in California is for the agricultural industry, and that rationing urban water won’t help much. But ignoring the reality of this drought is self-defeating.

“I kind of wonder about eating almonds. This is the stuff we learn in California now. It takes a gallon of water per almond. Beef. We eat less beef. We learned it takes 441 gallons to produce a pound of beef.

“We have a 14-year-old son. It’s important to talk about the drought with him. I was in a school bathroom the other day. There were signs above the sink: handwashing instructions for the kids. Something like, ‘Wet hands. Turn off water. Apply soap. Turn on water. Use one paper towel.’ I thought that was cool.

“People need to learn that. It’s the whole point. You have to think differently about water.”

Jeff Silberman, a Los Angeles entertainment attorney and literary agent who lives in Santa Monica, said he supports the city’s initiative to subsidize landscaping that replaces grass lawns with less water-intensive plantings.

The father of a 16-month-old son, Silberman is planning to more than double the size of his 1,200-square-foot home, which he’s owned since 1990. “We are remodeling with the drought, water shortage, and regulation in mind,” he said. “Drip irrigation for the garden and growing vegetables and fruit for ourselves. Basically, we figure water is at a premium, and the cost of food is going up.

“We see the handwriting on the wall. We saw it a year ago when we were looking for drought tolerant plants. I don’t want the place to look like dry gulch. You want to use as little water as possible, but I want it to look good. You know, you can find plants and flowers that don’t look like Death Valley. Mangos. Papayas. All kinds of food and flowers that don’t need a lot of water.

“Anybody who’s socially conscious knows it’s an issue. There’s nothing more important than water.”

Back in northern California, Ruth Leach-Stevens described how her family, which arrived in California from Ireland before the 1849 gold rush, so easily changes daily water use patterns during California droughts.

“In the late 1970s, there was a drought. In the late 1980s, too,” she said. “In Amador County it’s really second nature to us. We go immediately to Navy showers, not flushing toilets, using grey water. It doesn’t take much for us to respond. In the mountains during a drought, people know that every drop is dear.”

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!