America’s Spreading Septic Threat

Failing septic systems produce disease outbreaks, algae blooms, and ecosystem damage.

Jacob Stachnik, a worker at Concrete Service in Traverse City, Michigan, stands on a stack of septic tanks. Water pollution and diseases linked to septic system failures are becoming more problematic in the United States. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

There are 123 million households in the United States. Nearly one-fifth of them — some 21.5 million — do not flush toilet waste to a public sewer. They use septic systems — small underground tanks that provide basic treatment at relatively low cost for areas without sewers.

Countless more businesses, churches, and community centers employ the same means of waste disposal.

And while properly maintained systems operate just fine, the other side of this waste management practice is less benign. Because of neglect, age, or ignorance of hydrological conditions, failing septic systems, entirely hidden from public view, are producing a public health and ecological mess. Oversight and enforcement of operational requirements to keep septic systems from leaking raw wastes onto the land or into ground and surface water supplies is weak across much of outer suburban and rural America where most systems are installed.

Problems come from all directions. Hormones and pharmaceutical compounds, for instance, were found in the groundwater near septic systems on Fire Island, New York, and in New England, according to a January 2015 study from U.S. Geological Survey researchers.

Researchers with the Baylor College of Medicine are discovering a resurgence of parasitic diseases in rural Alabama because of poor sanitation and septic system failure. They will present their findings at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene annual conference, from October 25 to 29.

In Ohio, the state health department estimates that nearly one out of every three septic systems is failing.

Just how dangerous faulty septic systems can become was illustrated eight years ago at the Log Den, a steak-and-seafood restaurant on Wisconsin’s pastoral Door Peninsula. On June 1, 2007, three weeks after it opened, the Log Den unexpectedly closed. Two hundred eleven patrons and 18 staff members fell ill with norovirus, a stomach ailment that causes vomiting and diarrhea. The viral outbreak, in which six people required hospital treatment, was not due to the restaurant’s food. It was the water.

Though properly permitted, the restaurant’s septic system failed. Toilet wastes leaked into the ground, coursed through fissures in the soil and rock, and reached the limestone aquifer that supplied the restaurant’s water well. The foul waste mixed with fresh water used for drinking, ice-making, and lettuce-washing. The Log Den, in an inadvertent error unknown to its owner, had poisoned its own well.

Research Findings by Circle of Blue

An investigation by Circle of Blue found numerous other instances of septic systems that put homeowners and communities at risk. From New England to the Deep South and particularly in poor regions or areas with a dense clustering of septic systems near rivers or lakes, treating wastes with underground tanks and drain fields is emerging as another ruinous, and largely unaddressed, national water pollution challenge:

- Degraded bays, rivers, and lakes. Nationally, some 28,821 miles of streams are designated as “threatened or impaired” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency because of septic systems and pits of sewage waste — nearly equal to the number of stream-miles dirtied by municipal wastewater treatment plants and sewer overflows. Certain regions are severely affected. Sixty-nine percent of the nitrogen pollution in Long Island’s Great South Bay is from septic systems. One million people in Suffolk County, on the island’s east end, use septic systems. Because of nitrogen-fueled algae blooms, Great South Bay’s shellfish industry has collapsed, its eelgrass beds are nearly dead, and its storm-buffering salt marshes are dying.

- Parasitic diseases flaring up in the South. Poor counties in Alabama are seeing a resurgence of hookworm and other tropical diseases because of inadequate sanitation, which includes shoddy septic systems and toilet waste that is dumped into ditches, ponds, and ravines. By some estimates, half of the septic systems in Lowndes County, Alabama are broken. Researchers are just beginning to assess the problem of disease transmission and do not yet know infection rates.

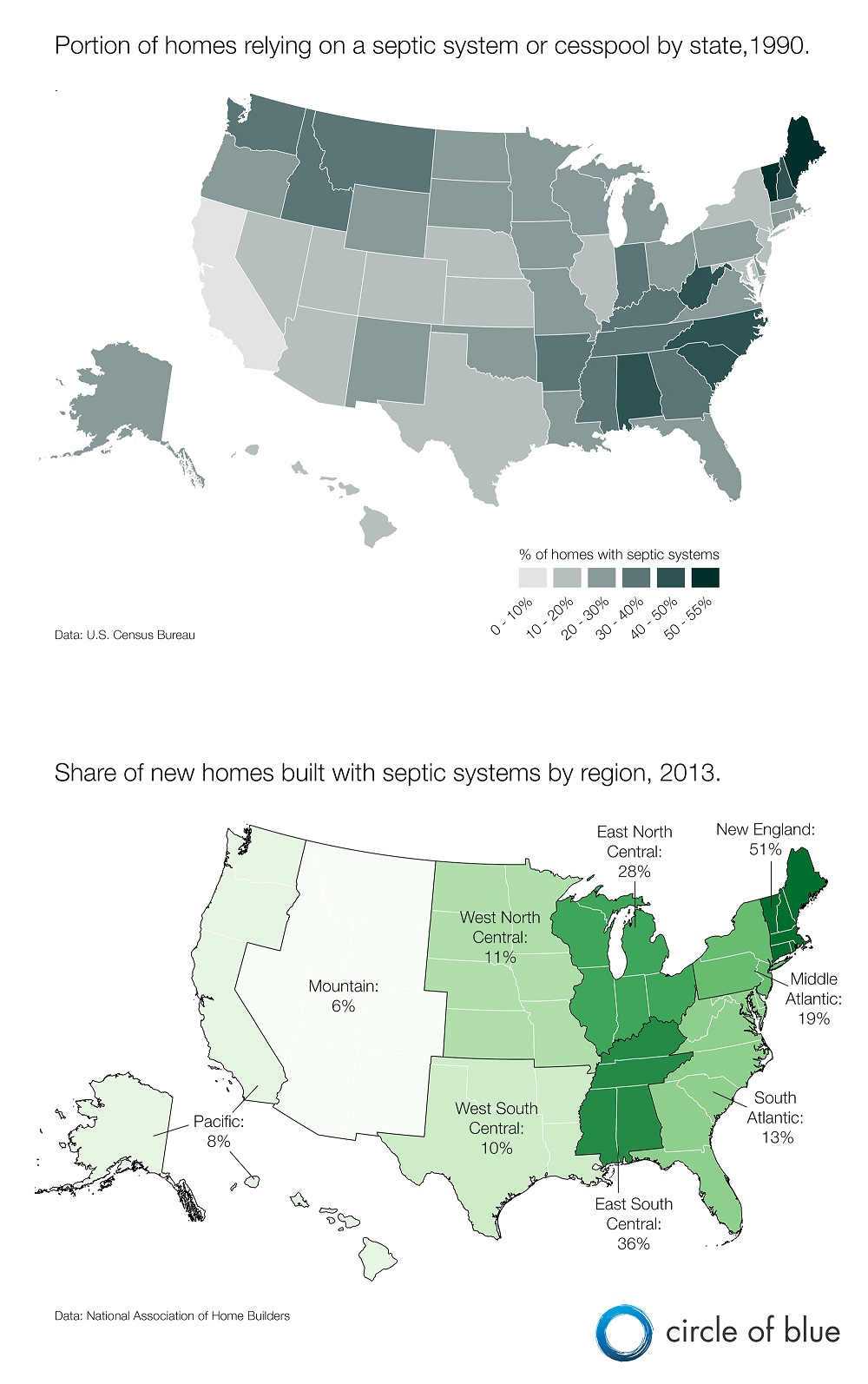

- Insufficient data collection. The U.S. Census Bureau stopped collecting county-level data on septic systems in 1990 because no federal program regulates septic systems. National data is gathered every two years through the American Housing Survey, which uses a much smaller sample size. A few states, like Georgia, have initiated septic mapping programs to pinpoint areas of concern. Likewise, there is very little reliable data on how many septic systems are failing. The numbers could be huge. The Ohio Department of Health, for example, estimates that 31 percent of septic systems in the state are not working properly.

- A hodgepodge of regulations. There are no federal regulations for septic systems. States set standards, often quite strict, for system design and installation that are supposed to be enforced by counties. Counties or towns in vulnerable or high-density areas sometimes set tougher standards. Maryland, for instance, requires nitrogen-removal technology on new buildings sited in ecologically sensitive areas or when old septic systems are replaced. Twenty-four other states have nitrogen regulations for septic. Most problems, however, begin after installation, as was the case with the Log Den restaurant.

- Irregular inspections. Many states do not require inspections after a system is put in the ground. Maintenance is the homeowner’s responsibility. Some states, such as Georgia, do not require homeowners or real estate agents to disclose that a house is on septic when it is sold, unless there is known damage to the system. Home buyers have to know to ask. Not knowing that a home is on septic means that system maintenance will not be done until the system fails.

- Research that is playing catch up. While there is ample research into septic system design, much less is known about the environmental and health effects of failing septic systems. Three topics are of special concern, according to researchers: 1) tracing the source of pathogens and the cause of disease outbreaks to septic problems, 2) learning more about the role that pharmaceuticals from septic systems play in water contamination, and 3) assessing how climatic changes — freeze-thaw cycles or intense rainstorms — affect the performance of septic systems.

Added up, failing septic systems and the threats they cause are a newly recognized and serious feature of the nation’s unaddressed water pollution problem. The United States already contends with the geriatric condition of America’s water infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave the country’s water supply and waste treatment systems a D grade in 2013. The average age of a Baltimore water main, to cite one example, is 75 years. Last week, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) proposed $US 1.8 billion in federal money over five years to help poor communities replace old sewer systems. Farm runoff, the country’s biggest source of water pollution, is now the target of Clean Water Act lawsuits. Polluted stormwater draining from cities and suburbs is a third unaddressed source of water pollution.

Blue Plains, which handles the wastewater for 2.3 million people in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., is one of the country’s largest sewage treatment facilities. Compared to municipal sewage systems, much less attention and money is directed at septic systems. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

But in the underwhelming national consideration of water pollution and infrastructure in Washington and state capitals even less attention and money is directed to septic systems. “There are no federal rules that address septic systems,” said Craig Mains, an engineering scientist at the National Environmental Services Center at West Virginia University. “Septic is not covered under the Clean Water Act. It is left up to the states and counties to decide how to regulate. There is a lot of variability state to state.”

Test of Values

America’s septic problem reflects one of society’s most enduring civic, political, and environmental questions: what is the balance between government regulation and individual responsibility? Septic systems usually proliferate in areas with an off-the-grid sense of independence and without strong ties to municipal services. The septic problem also cuts to the heart of the country’s most severe water pollution trials: toxic algae blooms, bays and coves choking from a lack of oxygen, and parasites, viruses, and bacteria that spread disease and misery.

“Septic has been successful for a long time, but we have to do better,” Joan Rose, director of Michigan State University’s Center for Advancing Microbial Risk Assessment, told Circle of Blue. “We’re adding more people, systems are aging, the climate is changing. We have a long ways to go in assessment of nonpoint sources of pollution.”

Like farm runoff, another nonpoint pollution source, septic problems are frequently neglected and difficult to assess. The septic challenge also has traits that are similar to the attempt to curb carbon pollution. Climate change is often described as a wicked problem — wicked because solutions are neither convenient nor quick. They require group action rather than an individual response.

Septic, though of a lesser degree, is of the same category. Like carbon pollution, no single homeowner is to blame for the ballooning nitrogen levels in a lake. It is a collective problem, the combined effect of many individuals with septic systems who live in a small area. It is a death by a thousand leaks.

Property Owner Responsibility

As urban America developed centralized sewage treatment facilities, septic systems still maintained a tenacious hold in suburbs and rural towns where the cost of building a community waste-treatment network proved too steep or politically impossible. Fifty-five percent of Vermont households, for instance, use septic systems.

For septic to work as designed, a chain of event needs to take place, explained Craig Mains of the National Environmental Services Center. The tank must be well designed. The drain field must be rigorously evaluated. Sandy or limestone soils that are too porous allow the waste to percolate too quickly into the water table, without time for microbes to convert it into beneficial organic matter. Soils that are too compact, like clay, cause the waste to flow into rivers and streams.

The drain field must also be located far enough away from waterbodies that the soil microbes have time to digest. Too much density is also bad for septic as it overwhelms the treatment capacity of the soil or raises the water table too high. Peter Groffman, a microbial ecologist at the Cary Institute for Ecosystem Studies, reckoned the ideal density, depending on soil and climate conditions, is one home or less per acre. On Fire Island, where U.S. Geological Survey researchers studied pharmaceuticals flowing from septic drains, the density is five homes per acre.

“If the systems are correctly designed and installed, if the site is properly evaluated, and if they are maintained, then they are pretty effective,” Mains said. “But they are as good as the weakest link in the chain. Often the weakest link is the homeowner.”

Mains said homeowners can wear down their systems in several ways. They might flush items that ought not be flushed. Paints, solvents, and antimicrobial soaps are toxic to the soil microbes that are enlisted to do the cleanup. Larger particles could clog the pipes that lead to the drain field, causing a backup. Or, homeowners might simply use too much water. A septic system is designed for a certain volume of daily use. Exceed that and the tanks fill too quickly.

“People don’t realize that you can’t use water indiscriminately with septic,” Mains said.

Many other researchers and regulators agree with the assessment that the challenge with septic is keeping the system in working condition after it has received a county permit and been installed.

“The problem comes after the septic system is in place,” Mussie Habteselassie, an associate professor at the University of Georgia who studies pathogens in soil, told Circle of Blue. “Maintenance is a big concern. Most contamination is from failing systems.”

“Homeowners are the weakest link,” Laurel Standley, principal at Clear Current, a water pollution consultancy, told Circle of Blue. “It’s difficult to get people to make changes.”

More Astute Oversight

Some jurisdictions are mandating behavioral changes. Conestoga Township, a community of small farms in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, passed an ordinance in 2014 that requires septic tanks be pumped every three years and inspected every four years. The township board cited water pollution and disease transmission as problems it wants to avoid.

Other jurisdictions are trying new approaches to overcome individual inertia. The Metro North Georgia Water Planning District, which covers 15 counties and 5 million people in the Atlanta region, is considering financial incentives to persuade people to clean out their septic tanks and maintain their systems.

Septic has been successful for a long time, but we have to do better. We’re adding more people, systems are aging, the climate is changing. We have a long ways to go in assessment of nonpoint sources of pollution.” Joan Rose, professor

Michigan State University

“You can do all the education you want,” Danny Johnson, the district manager, told Circle of Blue. “But until you get to people’s wallets you’re not going to see a change.”

Other states are coming at the problem with dollars in hand.

Maryland used the Bay Restoration Fund, which is seeded by fees collected from wastewater and septic system users in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, to install nitrogen-removing equipment on 6,550 septic systems. At the end of 2014, the fund had $US 83 million earmarked for septic system upgrades.

Suffolk County, New York, received $US 383 million in state and federal funds in 2014 that were tied to Hurricane Sandy disaster assistance. The money, which came from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant, will help connect 10,000 homes that are on septic systems to sewers.

Adding sewers, however, can be controversial. For one, a sewer system expansion is expensive, as the Suffolk County example shows. Second, extending a municipal piped system opens the door to rural growth. Because septic requires low density, developers can add more houses to a parcel of land if there is a sewer system. Johnson said that some counties in northern Georgia have a septic mentality because they want to preserve a rural feel.

Recovery

Two and a half weeks after the norovirus outbreak, the Log Den reopened for business. Inspectors discovered that although the system was installed properly, water from the septic tanks was leaking from a cracked pipe fitting. An extensive scientific investigation linked the cause of the well water contamination to the septic tank.

The restaurant purchased a $US 60,000 chlorination system for its drinking water, to kill any viruses that might enter the well. The water also goes through sediment filters, ultraviolet disinfection, and carbon filtration.

“It was very expensive, but what else could I do?” Wayne Lautenbach, the owner of the Log Den, told Circle of Blue.

As for patrons, the restaurant had to rebuild their confidence?

“For sure,” Lautenbach replied. “Even today I hear, ‘Is the water safe?’ I still get those comments.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Remember that one of the issues with decentralized and centralized wastewater choices is land use. Soil percolation rates are used to limit development. Also note that EPA wants municipalities to create management districts of decentralized systems. These qualify for Clean Water Act funds.

Thank you for providing the reports on cleaning. My tank hasn’t been cleaned in years. I’ll have to schedule and inspection.

Great article. Unfortunately seeing a lot of failed systems these days.