Lake Erie’s Bill Of Rights

Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Digital Visual Library

Update: The proposal has since been voted on and approved by Toledo, Ohio, residents.

Toledo, Ohio, residents will vote on an unusual and controversial proposal to steward their water – by giving Lake Erie its own legal rights.

Some Toledo residents have grown so frustrated in their attempts to protect Lake Erie that they are trying something new: asking that the Great Lake be granted the same recognition that people and corporations receive. They hope to amend the city’s charter with “rights of nature” to help fight toxic algal blooms that plague the lake.

In a special election on February 26, Toledo voters will consider a ballot initiative to establish “irrevocable rights for the Lake Erie Ecosystem to exist, flourish and naturally evolve,” and “a right to a healthy environment for the residents of Toledo.”

It’s called the Lake Erie Bill of Rights, and if it passes, it would show support for a growing global “rights of nature” movement, which is an effort to protect the environment by establishing legal rights for ecosystems.

In Toledo, the health of Lake Erie grabbed headlines in August of 2014, when a bright green mass clustered around the city’s water intake in the western part of the lake. The cyanobacteria, which appeared as a slimy, smelly green foam, produced a toxin harmful to humans and animals. The toxin got into Toledo’s water system and the city alerted some 400 thousand residents not to use their tap water. Not for drinking, not for bathing, brushing their teeth or washing their clothes.

Authorities said that the algal bloom in Lake Erie had created dangerously high levels of toxins that could cause rashes, vomiting and even liver damage. They warned that boiling the water would not make it safe, but only make it worse by concentrating the toxins. Local sources of bottled water sold out within hours, and the local news reported that people drove to other states to get water. Businesses shut down, and hospitals were only accepting the most seriously ill. For a few days, Toledo’s water was off limits, until the cyanobacteria mass floated away.

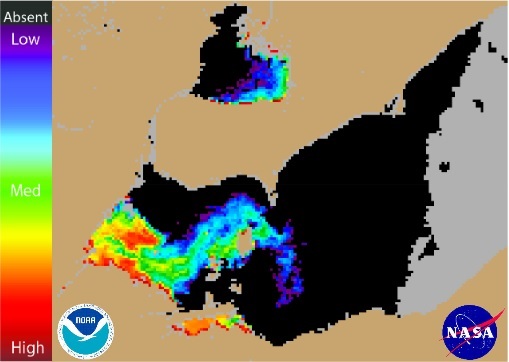

Toledo is currently working on a $500 million upgrade to its water treatment plant, but many residents have become leery about the quality and vulnerability of their water – especially since the algal blooms that cause cyanobacteria have become a summer phenomenon so large they can be seen from space. In 2015 and 2017, the algae in Western Lake Erie was worse than it was during the 2014 Toledo water crisis.

The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency says the blooms feed on phosphorus, which mostly comes from agricultural runoff from farms and feedlots. Other, lesser sources of phosphorus pollution come from sewage runoff and household detergents through septic systems.

After the 2014 water crisis, concerned citizens tried legal action against polluters whom they blamed for the algae. But they were frustrated by a lack of protections in state and federal law, and they sought another way.

Toledoans for Safe Water, a community group, worked with a Pennsylvania nonprofit, the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, to draft the Lake Erie Bill of Rights and to get the proposal on this week’s ballot.

The provision in the Bill of Rights that most worries industry and agriculture is this: that governments and corporations who violate the rights of the ecosystem are liable for harm. The Guardian described it as “effectively giving personhood to a gigantic lake…with the citizens being the guardians of the body of water…If passed, citizens could sue a polluter on behalf of the lake, and if the court finds the polluter guilty, the judge could impose penalties in the form of designated clean-ups and/or prevention programs.”

Although the concept sounds unusual, similar “rights of nature” ordinances have passed in cities including Pittsburgh, and Santa Monica, California. So people on both sides of the issue are taking this seriously.

A political action group called the Toledo Jobs and Growth Coalition has been running ads in opposition blaming the proposal on “out-of-state extremists”. It says that the law will impose financial hardship on Toledo families. A representative for the Ohio Farm Bureau, Yvonne Lesicko, said that the threat of ecological lawsuits is an additional burden on farmers and businesses that could discourage investors in the city’s economy. She said that farmers are concerned about Lake Erie and are trying to reduce phosphorus. But, reports Michigan Radio, most of these efforts are voluntary, and insufficient. Research shows that phosphorus flowing into the lake has increased 130% in recent years.

Joe Logan, president of the Ohio Farmers Union, represents small and medium-sized farmers. He told Marketplace Radio that farmers needn’t fear the Lake Erie measure if they are “doing things right and taking care of livestock, acreage and crops in a responsible manner …Nobody wants to have somebody looking over their shoulder,” he said, but if the Lake Erie Bill of Rights forces farmers to “be more judicious and careful in managing their operations, then that may be an idea whose time has come.”

Michelle Maloney, co-founder of the Australian Earth Laws Alliance, says that the idea is indeed getting growing attention around the world as people push back against the destructive effects of industry upon their communities and ecosystems.

She gave examples of places where the legal rights of nature have been changed in constitutions, laws and in court: Ecuador’s Vilcabamba River, New Zealand’s Taranaki Mountain, and Columbia’s Atrato River. She said that in Australia, her organization is pressing beyond laws that protect the Great Barrier Reef, because many types of destructive activity are still legal.

Maloney said the drafters of the Lake Erie Bill of Rights share the understanding that existing law cannot protect and restore the lake and she encouraged a new legal paradigm. “This,” she said, “is a powerful way to push back at a legal system that privileges government control and corporate rights, over the legal rights of local communities and the living world.”

Howard Learner is with the Environmental Law and Policy Center. In his view, a new legal approach isn’t necessary. He says the U.S. EPA could and should fully enforce the Clean Water Act, focusing on the worst polluters – the large-scale corn, soy and animal feed lot operations – and not the small farmers. “In the best of worlds,” he told Michigan Radio, “U.S. EPA would step up and say to the Ohio EPA ‘you have to act now to aggressively reduce the amount of manure and other phosphorus runoff going into western Lake Erie.’”

The New York Times reports that the issue has put Toledo’s elected official in a difficult spot. If they oppose the measure, they could appear as enemies to the lake and the environment. But it they support it, the bill of rights could mean tens of thousands of dollars in costs for the city to defend it against legal challenges.

And on that point everyone agrees. Ohio attorney Terry Lodge, who helped shape the bill says there will be extensive litigation to sort things out, and similar “rights of nature” laws have fared poorly in court. For example, key parts of the proposal may conflict with state and federal law, and groups on all sides will be angling for their own interests. But Lodge told the Guardian that those finding fault are missing the point about why a bill of rights for a lake came about in the first place. He said “The people in Toledo have realized for a long time their water and their health was in danger from excessive pollution in the lake. Over the years they called for the cavalry repeatedly to help them. But the cavalry never came. So they have decided to be their own cavalry.”

Eileen Wray-McCann is a writer, director and narrator who co-founded Circle of Blue. During her 13 years at Interlochen Public Radio, a National Public Radio affiliate in Northern Michigan, Eileen produced and hosted regional and national programming. She’s won Telly Awards for her scriptwriting and documentary work, and her work with Circle of Blue follows many years of independent multimedia journalistic projects and a life-long love of the Great Lakes. She holds a BA and MA radio and television from the University of Detroit. Eileen is currently moonlighting as an audio archivist and enjoys traveling through time via sound.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!