Trump Proposal to Fix U.S. Water Infrastructure Invites Large Role for Private Investors

Private-public partnerships, a potential funding source, are complicated and controversial.

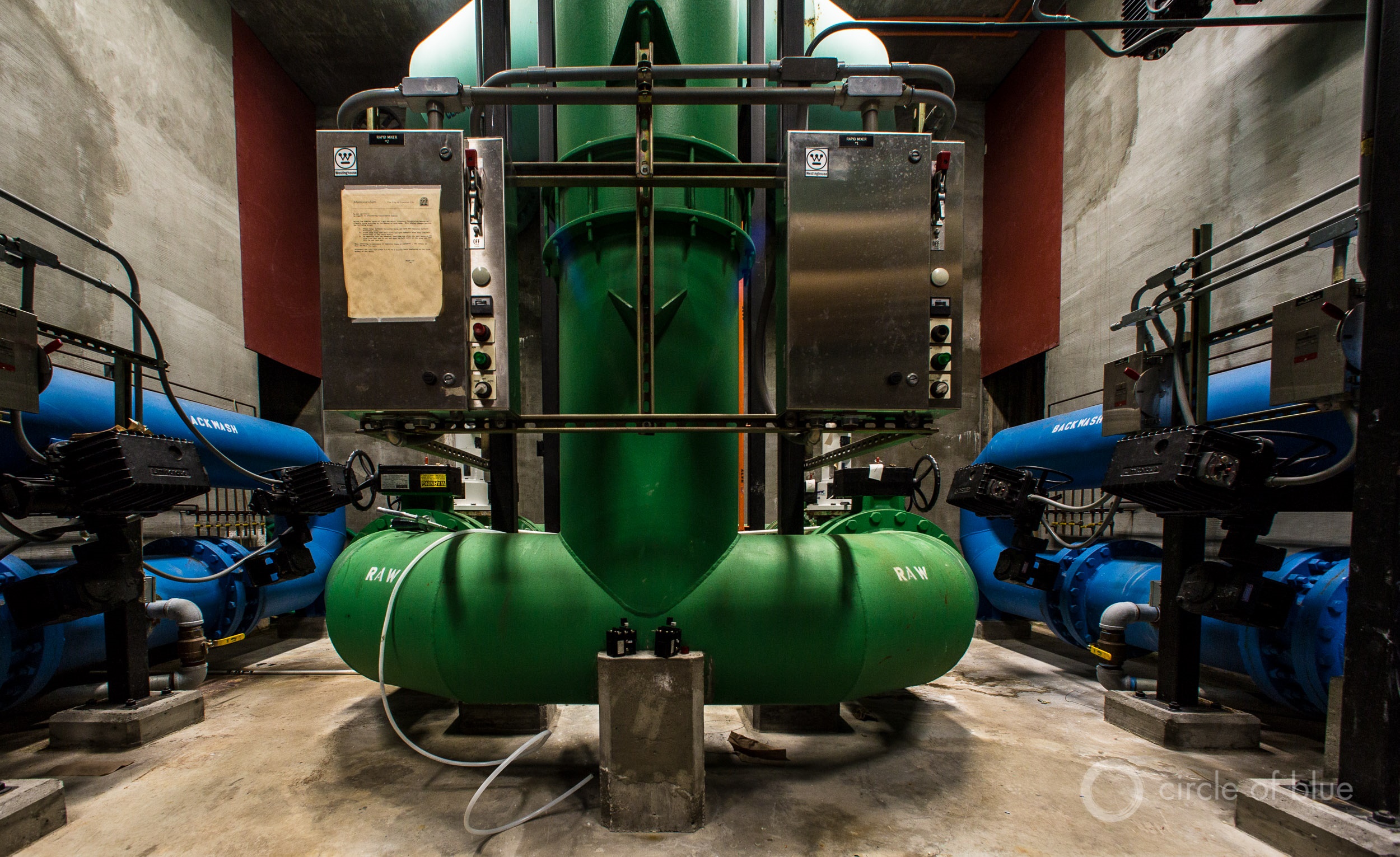

The role of investor-owned companies and private equity firms in financing, operating, and maintaining U.S. water infrastructure is a source of renewed debate. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

President Donald Trump, fashioning himself the builder-in-chief, promised to invest $US 1 trillion to make America’s potholed highways, unstable bridges, leaky water systems, strained ports, and brittle levees whole again. The pledge is more a slogan at this point. Still, Trump and his advisers are adamant that such a big bet on the nation’s arteries of commerce, health, and safety come with a large role for investor-owned companies and equity firms to form public-private partnerships, or P3s.

More common in the transportation sector, P3s have garnered support in Congress from both political parties as a source of funding to fix America’s water infrastructure. Advocates tout better services and lower operating costs. Private partners are more readily able to take on the financial risk of construction delays or faulty equipment. Backers also point to a pile of private money that could address the $US 633 billion in spending that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that water utilities will need in the next decade to maintain service.

There is little debate about the urgency of modernizing America’s transport, transmission, and water supply networks. Many have surpassed retirement age. Others, in an era of powerful storms, renewable energy, urban growth, and extreme temperatures, do not match changing environmental and economic conditions.

But the repair bill, especially for water, arrives in the offices of municipal and county leaders who are sometimes reluctant to raise rates or taxes to pay for the remodeling. Local officials, facing state and federal water pollution mandates, limited budgets, maxed out debt loads, and the potential for citizen wrath at rate increases, feel the money pinch. They understand the need to invest in water but are restricted in their response.

These formidable trends, moving on a collision course, are the reason that municipalities implore the federal government to do what it did until the mid-1980s during the post-Clean Water Act expansion of the nation’s wastewater treatment facilities, which is to pick up much of the tab.

But those days are long gone and Republican lawmakers, trained and fed on a political formula that heaps scorn on any mention of increasing tax revenues for public purposes, have indicated no particular interest in ponying up for infrastructure spending. Thus the emergence of public-private partnerships in American municipal water supply systems.

Depending on how they are counted and defined, there are anywhere from five dozen to nearly 2,000 public-private partnerships in the U.S. water sector. They aren’t especially popular, though, and generate storms of opposition.

Opponents argue that P3 contracts, though they often provide much needed upfront payments to municipal governments, are a quick-fix for communities in financial distress. Higher water rates are a burden to residents, and multi-decade contracts are difficult to renegotiate. Critics also cite lawsuits against contractors such as Veolia for alleged management failures in two states.

Michigan filed a civil suit in June 2016 against Veolia and Lockwood, Andrews, and Newman, an engineering services firm, for negligence and fraud related to the Flint lead scandal. The suit claims that the defendants ignored the warning signs of corrosion in the city’s water system. The Flint lawsuit followed the Massachusetts attorney general’s lawsuit against Veolia in April 2016 for failure to maintain the wastewater system in the town of Plymouth.

The idea that water utilities need capital and the private sector has capital and we just need to connect the two is a dangerous oversimplification.” — Jeff Hughes, director UNC Environmental Finance Center

More recently opponents have criticized a new option: the WIFIA program, a low-interest loan program approved by Congress in 2014 and administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Targeting large projects of regional significance, WIFIA is open to P3s, and the window for submitting letters of interest for the initial round of funding — estimated to finance up to $US 2 billion worth of projects — opened in January.

Opponents say that the government ought not to subsidize the private sector when there are existing federal water infrastructure programs that offer financial aid to the poorest communities. Rural utilities in particular favor expanding EPA’s state revolving funds and USDA’s water and wastewater grants because they are the cheapest, and sometimes only, source of financing for communities too small to issue low-interest municipal bonds.

Investors are excited but wary of the new program. They told Public Works Financing, a newsletter that tracks private sector deals, that EPA’s endorsement on WIFIA could help jumpstart a slow-growth P3 market that has seen no sizable contracts in the last two years. But some of the program’s restrictions on how quickly money can flow to private partners are a potential hang up.

A new study from the University of North Carolina’s Environmental Finance Center, one of the country’s foremost organizations for analyzing utility finances, adds nuance to this debate. It found “neither miracles nor devastation” for utility finances in nine P3 deals it studied in the United States and Canada, according to Jeff Hughes, the report author.

Nearly every community in the study touted the potential for cost savings. But the report did not find much evidence that that was the case. In fact, the contracts were complex documents that required significant time and oversight to execute. Utilities instead benefited from higher-quality facilities, more responsive service, guaranteed performance targets, and money to pursue municipal goals not related to water service such as paying for pension benefits.

Hughes, the center’s director, notes that private dollars, while helpful in certain circumstances, are not a “magical solution” that will heal deep-rooted problems that caused some of the utilities in this group of nine to seek out a private partner: mismanagement, financial distress, or a public agency’s unwillingness or inability to raise enough revenue to maintain systems.

In a rigidly partisan American political environment, infrastructure spending is perhaps one arena of cooperation. Rejecting all other Trump initiatives, Democrats are nonetheless encouraged by the president’s seeming willingness to champion public works.

They do differ, however, on the source of funding. For Democrats, public money is a far greater slice of the pie. Four days after Trump’s inauguration, Senators Patrick Leahy and Bernie Sanders, a Democrat and an Independent from Vermont, and Senator Charles Schumer, a Democrat from New York, published their own blueprint for rebuilding U.S. infrastructure. The $US 1 trillion plan includes $US 110 billion in grants and low-interest loans for drinking water and sewers but also endorses an expansion of the WIFIA program.

The exact ratio of public to private funding in a federal infrastructure package will be worked out in the coming months. President Trump will send his budget proposal to Congress on March 16 and flesh out his infrastructure plan later this spring. Hughes cautions that when determining a role for the private sector, elected and utility leaders should not assume that setting loose herds of private capital will automatically result in success.

“The idea that water utilities need capital and the private sector has capital and we just need to connect the two is a dangerous oversimplification,” Hughes told Circle of Blue. P3 deals are sophisticated financial and technical arrangements that, if well-designed, can result in public benefits, but they aren’t a silver bullet solution. In other words, Hughes said, the relationship between private capital and public infrastructure is not like putting a plant in water. “It’s not just pour here and watch it grow,” Hughes said.

What Does Grow?

The concept for the UNC Environmental Finance Center’s study — an autopsy of whether promised financial results were actually delivered — piqued Hughes’ interest. Many assessments of P3s, he thought, were inadequate. Proponents such as the National Council for Public-Private Partnerships produced cheerleading reports that highlighted mostly successes. On the other side, Food and Water Watch, which campaigns for public water, and similar groups view with suspicion the private sector’s advance into municipal assets.

The study, funded by the EPA, sheds light on how well partnerships have performed by examining an aspect of P3s that is often used as a selling point: that they are better for a utility’s bottom line.

Researchers drew lessons from eight case studies in the United States and one in Canada. They discovered exaggerated promises and unforeseen pitfalls as well as projects that were successfully implemented.

“We found much more nuanced outcomes than we had been led to believe from a general review,” said Hughes, the center’s director.

The study examined a variety of partnerships designed to execute midsized water utility projects, those in the $US 75 million to $US 200 million range:

- Concession agreements in which a private entity managed the entire water system or a particular facility

- Design-build-operate arrangements in which a private group built and operated a new treatment plant but the public agency retained ownership

- Service purchase agreements in which a private entity built a desalination plant or water recycling facility and sold water to a public utility

- Partnerships between two local governments

Hughes stressed that the cases studied were not privatization deals. None of the utilities sold existing assets. In all cases, ownership of the system remained in public hands.

A number of lessons emerged from this collection. One, private capital is not cheap. Equity partners expect a return on investment of between 10 and 20 percent, a far higher interest rate than the roughly two percent that a public utility would pay through the state revolving fund, a federal loan program for water infrastructure, or the five percent from a tax-exempt municipal bond.

In none of the nine examples was private equity the exclusive financing source. Most used a mix of municipal bonds, bank loans, and government loans that brought the blended interest rate significantly lower than if private equity were the only source of capital.

Private entities expect a higher rate because they take on the risk associated with construction delays, permitting challenges, or simply trying something new — an alternate energy source perhaps or a facility design that might cost more to build but will reduce long-term operating costs.

Hughes said that policymakers and public officials should not confuse two related but separate concepts: capital and revenue. What might appear for U.S. water systems to be a capital problem — lack of upfront money — is actually an issue of revenue: an inability to pay back what was borrowed. “For many systems the problem is not a lack of capital but the ability to raise revenue sufficient to compensate capital providers,” Hughes explained.

Water rates are often controlled by elected officials who often are unwilling to approve higher expenditures, especially in a poor city where affordability is already a concern. Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy at the Center for American Progress, made the same point about capital and revenue at a U.S. House committee hearing on March 9. “For many cities and water utilities, access to affordable credit is not the binding constraint. Instead, there is a shortage of local revenue to support new project debt,” he said.

No Free Lunch

The second conclusion from the UNC study is that you pay for what you get. Many P3 deals resulted in significant rate increases, but the increase was linked to better customer service, repairs to leaky pipes, and new facilities. The UNC researchers found no evidence that improved service and new investment in a P3 deal can happen while reducing rates at the same time.

Rialto, California, for instance, anticipated a 115 percent rate increase over four years after signing a 30-year concession agreement in 2012. But the city also was able to pay down debt, repair the wastewater system, and store money in reserve funds.

Third, deals are frequently about more than infrastructure. Several of the cities in the study used a P3 deal to put out fiscal fires in other municipal departments. Allentown, Pennsylvania, for one, executed the equivalent of a home mortgage in its concession agreement with the county government. The city converted some of the equity value in its water system into a $US 211 million lump sum payment. In return, the Lehigh County Authority operated the water and sewer system and collected customer payments based on a rate schedule established in the contract. Allentown used the cash to pay down pension obligations.

In a separate case, Bayonne, New Jersey, entered into an agreement in 2012 with United Water, a water services company, and KKR, a private equity firm, to operate and maintain the city system for 40 years. Bayonne used more than 80 percent of its $US 150 million upfront lease payment to pay off water utility debt that had accumulated because of inadequate revenue. Bayonne also used $US 18.5 million from the deal to cover general operating expenses in the city budget and to slow the increase in local property taxes. In both examples, the study notes, P3s provided community benefits beyond the water system, largely by patching budget holes. These benefits flowed to certain community members — pensioners and property owners — but the cost was shifted to water customer bills.

The utilities in the study also used P3 contracts to lock in performance expectations and hold the private entity responsible for actions that public officials were unwilling to do. This was the case in Bayonne, which hadn’t raised rates in the six years before its P3 deal despite increasing water utility debt and declining water sales. The private partners agreed to spend $US 2.5 million per year, adjusted for inflation, over the 40-year contract on capital improvements and $US 500,000 per year on maintenance.

What the partnership does is remove the need for political will for the maintenance of the system.” — Tim Boyle, executive director Bayonne Municipal Utilities Authority

“What the partnership does is remove the need for political will for the maintenance of the system,” Tim Boyle, executive director of Bayonne Municipal Utilities Authority told Wharton Business School researchers. “It’s hard to imagine politicians committing an equal amount of money to maintaining our water supply.”

Hughes said the contract was a way of guaranteeing investments that local officials might not make. “It’s a way of protecting themselves against themselves,” he remarked. Like giving the car keys to a sober friend before going to the bar.

Fourth, P3s are buffeted by the same declines in water demand that are destabilizing water utility finances in general. None of the private partners in the nine case studies was willing to take on the risk of losing revenue because of reduced demand. If water use projections are off, and utilities frequently overestimate demand, then revenue will fall short. If that happens, rate increases beyond what was sold to the public become necessary.

This happened in Phoenix, where water demand in 2010 was 16 percent lower than had been forecasted a decade earlier. The 40 million gallons of water Phoenix had contracted to buy each day from the Lake Pleasant Water Treatment Plant was nearly superfluous. The plant, built using a P3 model, was approved when water demand expectations had been much higher. In the end, Phoenix water managers were able to renegotiate the contract to 25 million gallons per day, a savings to the city of $US 1.1 million per year.

Declining demand also plagued Bayonne, where a four percent rate increase in 2015 was followed by a 13 percent jump in 2016. The reasons, according to the study, were complex. New water meters mandated by the contract were more accurate and allowed for earlier detection of leaks, thus less water was lost. The utility authority, meanwhile, did not put any of its concession money into a rate stabilization fund that would be tapped when revenue was short.

Above all, said Hughes, well-designed P3s offer a number of benefits for utilities and communities. They can transfer the risk of construction delays and overruns to private entities and provide short-term financial flexibility. The deals can also result in facilities that employ new technologies that are costlier up front but deliver long-term savings from lower operating expenses. But P3s are not a cure all. Revenue expectations ought to be moderated by keeping an eye on the persistent decline in urban water demand. Writing a fair contract that ensures the right investments are made is not easy and borrowing costs are higher if using private capital, Hughes emphasized.

“I think there is a role for private capital, particularly for larger projects, but it’s not going to be the missing source of capital for many systems,” he said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton