Mismanagement of Abundance: Constellation of Coal Mines Across India Not Enough to Prevent Blackouts

Despite the push for renewable energy alternatives to address water and climate concerns, India plans to keep coal as its primary source of electricity. But corruption, bureaucracy, slow environmental reviews, and inefficient transmission lines are hampering domestic production and causing unstable power supply.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

BILASPUR, Chhattisgarh, India — If there is a region where India’s resource-driven economic ambition has the potential to succeed, it is here in Chhattisgarh, a water- and energy-rich eastern state comprised of coal-dusted cities and a constellation of open-pit and underground mines that spread across the countryside like black stars.

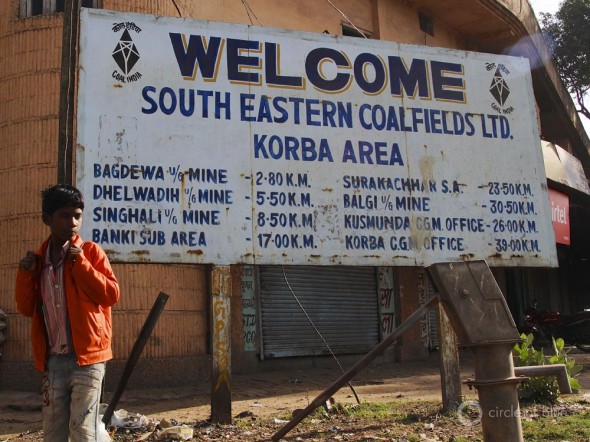

Here in Bilaspur, the region’s industrial governance is decided, by and large, from within a warren of glassed-in offices at the corporate headquarters of Southeastern Coalfields Ltd., the largest subsidiary of Coal India, the world’s largest coal company.

One of the most spaciuous offices on the second floor belongs to Sinha Subrata Shekhar, the 51-year-old general manager of corporate services who is one of the company’s highest ranking executives. Candidly, Shekhar describes the cross-cutting challenges — corruption, labor strife, political infighting, bureaucracy, slow environmental reviews — that are hampering India’s coal industry, limiting electricity production, and weakening its economic growth.

“In India,” Shekhar shrugs, “we have paradoxes.”

No doubt about that. The agriculture sector consumes 19 percent of the nation’s electricity, and 65 percent of that power is fueled by coal. One of every five metric tons of the coal that India produced in 2012 came from Chhattisgarh. But domestic coal production is not keeping up with rising demand for electricity. Despite that India is the second-largest coal importer behind China, much of the nation still suffers from irregular power supply and periodic blackouts.

Southeastern Coalfields and its 62 mines in Chhattisgarh are links in a chain of risk that stretches well beyond here, since national food production and city-wide blackouts so closely hinge on the coal coming out of this region. Most abundant in Chhattisgarh and the neighboring eastern states of Jharkhand and Odisha, India’s coal belt cinches the nation round the middle, tapering off in its westward stretch to both the south and north, as if giving way for the major grain-producing states of Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh.

By no means, however, is the escalating contest for water between food and energy solely a matter of resource scarcity. In many ways, in fact, India’s mounting confrontation between the three vital inputs is a product of abundance and mismanagement.

“The resources are available,” Shebonti Ray Dadwal told Circle of Blue. She is a research fellow and energy security expert at the Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis in New Delhi. “We are pushing very hard to improve India. We have problems. Lots of problems. But this country can succeed.”

Yet from the perspective of farmers, urban residents, and other industries, the jury is still out on whether such optimism is rational.

A Big River, But Enough Water?

In Tilda, just 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Bilaspur, a new water-transport pipeline and a nearby coal-fired power station are useful cases in point.

On the way to Tilda, a farming town surrounded by rice paddies and wheat fields, the two-lane highway skirts a construction site where lengths of steel pipe — each as long as a fence and as wide as a truck tire — lie at the bottom of a deep trench. Further along the highway, no more than 10 kilometers (six miles), the towering steel superstructure of a giant 1,370-megawatt coal-fired power plant, also under construction, emerges from the afternoon haze.

When the pipeline is completed next year, it will draw water from the Mahanadi River, according to the state environmental compliance report that was prepared by GMR, an infrastructure development company that is the owner of the new generating station and which is named for its founder, Grandhi Mallikarjuna Rao. Annually, 32 million cubic meters (8.45 billion gallons) of water will make the 40-kilometer (25-mile) trip from the river — Chhattisgarh’s primary source of surface fresh water — to produce steam and to cool generators at the GMR power plant, which also is expected to be completed in 2014.

The Mahanadi River, long and wide, runs north and then east 885 kilometers (550 miles) through central Chhattisgarh and neighboring Odisha to the Bay of Bengal. The river drains a 66,000-square-kilometer (25,000-square-mile) region that includes northern Chhattisgarh, rich in coal reserves and home to more than a dozen huge new coal-fired, water-consuming power plants.

According to the Chhattisgarh Electricity Board, 73 percent of the state’s existing electrical production already relies on the Mahanadi. Along with the GMR plant, some 58,000 megawatts of new generating capacity is planned in Chhattisgarh, according to the state power agency. Almost all of that electricity — equivalent to 58 big generating stations —will be produced with coal, and 80 percent of these new plants will draw water for steam and cooling from the Mahanadi.

In the view of state and national government leaders, as well as many business executives, this apparently useful collaboration between a new water-transport pipeline and a new coal-fired power plant in Tilda reflects Chhattisgarh’s determination to raise more of its 25.5 million residents from mud-hut poverty to the middle class.

But many say the project is an industrial over-reach and a decided risk to the well-being of others who use the Mahanadi. In December 2012, representatives of 32 communities, farm groups, and non-profit organizations from Chhattisgarh and Odisha held a two-day conference, Building a People’s Agenda for Management of River Mahanadi, on the tightening contest for the Mahanadi’s water.

“The river is a common resource of people. They should get priority in its water,” Gautam Bandhopadhya told reporters during the December conference, according to local news reports. Bandhopadhya leads Nadi Ghadi Morcha, a Raipur-based environmental group that co-sponsored the meeting.

Some 40 million people — most of them farmers — in both Chhattisgarh and Odisha depend on the river according to Water Initiatives Odisha, the event’s other co-sponsor.

“There should be joint movement from both the states to fight rapid industrialization and its impacts on the Mahanadi,” said Prafulla Samantara, an environmental leader who attended the meeting, according to local press accounts.

Still, along with the power generation that is planned for Chhattishgarh, Odisha wants to build 75,000 megawatts of new generating capacity — or 75 big power plants — of its own over the next few decades. And like the 58,000 megawatts in Chhattisgarh, 80 percent of these new plants will also be fueled by coal and will rely on Mahanadi water, according to Water Initiatives Odisha.

Abundance and Mismanagement

When it comes to India’s water-food-energy nexus, the problem is not that water reserves are low. India’s annual renewable water reserves total 1,608 billion cubic meters (425 trillion gallons) a year, ranking it ninth in water supply among the world’s nations, according to the CIA World Factbook. Ample rainfall and snowmelt enabled the nation’s farms, cities, industries, and power sector to last year use 694 billion cubic meters (183 trillion gallons) of fresh water annually — 15 percent more than what is used each year in China and 22 percent more than in the United States — according to India’s National Institute of Hydrology.

Nor are India’s coal mines barren. With 67 billion metric tons of proven reserves still to be mined, the nation has the world’s fifth-largest coal storehouse, according to figures from the World Energy Council. Last year, India mined 540 million metric tons of coal, ranking it third in production behind China and the United States, according to the World Coal Association, the industry’s London-based trade group.

India’s newest Five-Year Plan calls for coal mining production to climb almost 80 percent by 2017. In other words, India is counting on its coal reserves to fuel most of its electrical power plants for the foreseeable future.

But like so many other facets of its planning, India’s capacity to mine that much coal is in question. Consider that from 2006 to 2012, coal production grew from 431 million metric tons to 540 million metric tons, an average annual increase of 18.1 million metric tons. The new Five-Year Plan calls for production to increase an average of 90 million metric tons annually, a rate of increase matched in recent decades only by China — and never by India.

Furthermore, even though India’s coal-fired capacity is currently growing by nearly 20,000 megawatts annually, much of the nation still suffers from widespread blackouts. The reason: consumption of electricity is growing nearly 7 percent annually, according to the International Energy Agency, while the domestic coal supply — even with growing imports — is increasing by less than 4 percent annually.

During 2011-2012, national demand for coal reached 652 million metric tons, 70 percent of which was used in coal-fired generation, according to India’s Ministry of Coal. But since India only mined 540 million metric tons, the nation had to import 112 million metric tons — nearly equivalent to what it pulled out of Chhattisgarh’s mines that year. India, as a result, is the world’s second-largest coal importer, behind China.

But it still was not enough.

A 2012 Planning Commission report found that, of the 48,894 megawatts of new coal-fired generating capacity that India developed from 2007 to 2012, “25,000 megawatts of coal-based capacity is being sub-optimally utilized, because of inadequate availability of coal.”

Translation: according to the Planning Commission, half of the country’s newest coal-fired plants are idle, in whole or part, because they cannot secure adequate supplies of coal to fuel them. At the end of September 2012, 35 coal-fired power plants had seven days — or less — of fuel in supply, according to India’s Ministry of Power. Last summer, half the nation went dark for days in July, an event that attracted global attention but was shrugged at by Indians who are accustomed to frequent and lengthy power outages.

So Many Cross-cutting Issues

A torrent of unresolved issues account for the coal shortages, explained Shekhar of Southeastern Coalfields:

- Bureaucratic torpor: Proposals to expand any mines involve a long agency-by-agency, office-by-office process of securing permits from India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests, as well as from state-level agencies. Each of the provisions in each application, Shekhar said, must be reviewed and signed by state and federal offices going up the chain of command. “They must go up all these levels and then come back down through the same levels,” he said. “It takes years and years.”

- Rampant corruption: The lobby of the Southeastern Coalfields building displays a big white sign with blue lettering that describes another impediment. “Do not pay bribes,” it warns. “If you are a victim of corruption in this office, you can complain to the head of the department.” Bribery, theft of equipment and coal, illegal trade in permits, and organized crime gangs are endemic. For example, the national government is currently investigating the mishandling of coal leases and permits in one of Coal India’s other subsidiaries, and authorities are investigating thefts of coal by criminal gangs throughout the mining region.

- Frequent strikes: In February 2013, workers shut down Southeastern Coal’s massive open-pit mine in Gevra — which is the largest mine of its kind in Asia and the second-largest in the world — that is responsible for almost 30 million metric tons of production annually, according to company production records.

- Insufficient transportation: India’s rail system is not large enough to efficiently transport coal from the coalfields in the east to power plants in the west and north, where a sizeable portion of the country’s coal-fired generators operate.

Water Waste and Climate Change

India’s drying climate and inefficient water use policies also are factors. The annual mean rainfall nationally has dropped 8.9 percent over the last 50 years, according to the India Meteorological Department, and droughts have become more frequent and punishing.

For instance, a 2004 winter drought dropped the generating capacity of three coal-fired power plants in Delhi by 80 percent, according to the Delhi Pollution Control Board. During a 10-year period from 1995 to 2005, the Rayalaseema coal-fired plant operated sporadically due to water shortages. And in 2009, a drought in Chhattisgarh and Odisha lowered water levels in the Hirakud Reservoir so dramatically that the generating capacity of the Burla hydropower plant dropped from 307 megawatts to just 17 megawatts.

Such trends test the limits of India’s water supply and electrical generating capacity. In central and eastern India, as utilities are building coal-fired generation, communities become more restive about the quantities of water needed to operate the plants — and there are legitimate reasons for them to be worried.

Though 543 billion cubic meters (143 trillion gallons), or almost 80 percent of India’s water use, was for agriculture in 2010 and just 14 billion cubic meters (3.7 trillion gallons), or 2 percent, was for the power sector — mostly coal, but also a little nuclear, natural gas, and biomass — water use in the coal-fired power sector alone is forecasted to nearly double to 25 billion cubic meters (6.6 trillion gallons) annually by 2025, and it will double again to 50 billion cubic meters (13.2 trillion gallons) by 2050, according to India’s latest Five-Year Plan.

This represents the largest forecasted increase in water use for any sector in India.

Once again, at the root of the big jump in water use is India’s newest Five-Year Plan, which calls for adding more than 69,000 megawatts of new coal-fired generating capacity by 2017, as well as for coal demand to reach 980 million metric tons annually by the same time. Moreover, imports, which account for less than 20 percent of the coal supply today, could climb to more than 200 million metric tons annually, or 22.4 percent of the projected supply, according to India’s Planning Commission.

But what if India is unable to increase production as the Five-Year Plan proposes?

Back in Tilda, GMR has already alerted Chhattisgarh’s electrical supply authorities of how it plans to deal with the anticipated shortage of coal: in environmental compliance filings with the state, the company said that it would import its fuel supply from South Africa when the plant — and the associated water pipeline — come online in 2014.

Map by Jinah Park, undergraduate student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. Photos by J. Carl Ganter and Aubrey Ann Parker, Circle of Blue’s director and news editor, respectively. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact, jcganter@circleofblue.org, and circleofblue.org/contact.

Choke Point: India is produced in collaboration with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and its China Environment Forum, with support from Skoll Global Threats Fund. The Wilson Center’s Asia Program, which provided research and technical assistance, produces substantial work on natural resource issues in India, including articles and commentaries on energy, water, and the links between natural resource constraints and stability.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

India’s population growth and attempts to develop sufficient power, and water infrastructure, under the guise of a democracy, is fascinating. When the country experienced a massive power outage at the end of July 2012, everyone blamed everything (policy, politics, planning, power managers) but no one looked overhead and saw the spaghetti of power lines that illegally tap power from the grid, as a problem:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/01/world/asia/power-outages-hit-600-million-in-india.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

One of the commentator to the NYT article rightfully pointed out:

“For those predicting a similar outcome here in the US regarding its power grid, you need to calm down.

Unlike the US, the Indian electricity market is highly regulated with below cost pricing being provided to residential consumers. Thus, this subsidized pricing scheme has Indian utility companies constantly short on needed cash to help maintain their infrastructures. Also, despite highly subsidized pricing, electricity theft in India is rampant causing a poorly maintained power grid to become even more dysfunctional.

Therefore, to all you Chicken Littles, while the sky may be falling in India, it does not necessarily mean it will also occur here.”

Thank you for this article. I appreciate living in the US more, every day.