Earth’s Major Aquifers Are in Trouble

Groundwater reserves are falling, but little is known about how much water is left.

The world is perilously ignoring the water crisis that is occurring underfoot, writes Jay Famiglietti in the journal Nature Climate Change.

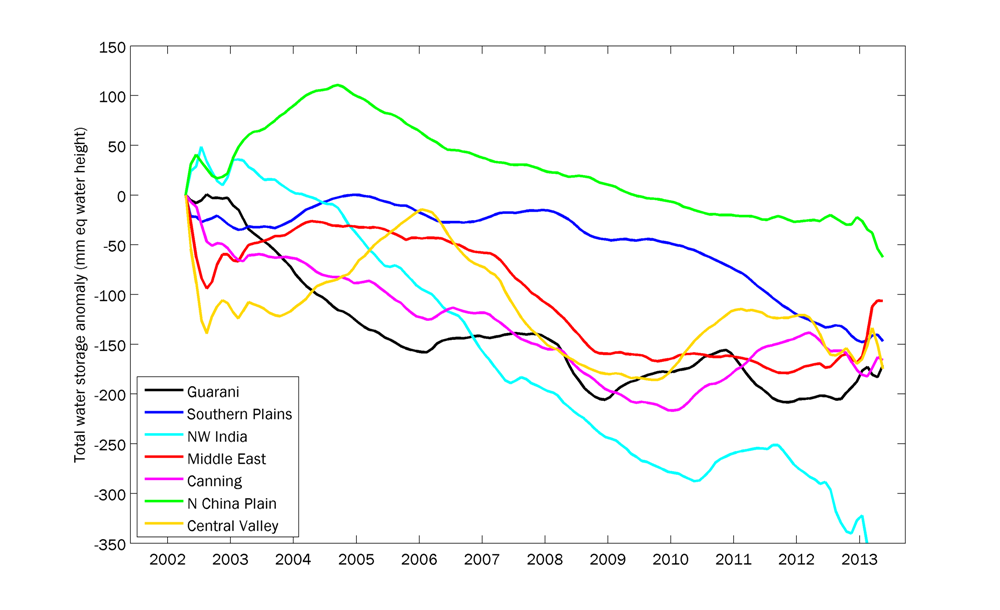

A professor of Earth System Science at the University of California, Irvine, Famiglietti has helped refine the premier tool for understanding large-scale changes in groundwater reserves. Measurements from NASA’s GRACE satellite mission, launched in 2002, have revealed unsettling trends in the world’s major aquifers: they are almost all declining.

Sound management of new demands for water requires a better understanding of the supplies available, according to Famiglietti.

“Full appreciation of the importance of groundwater to the global water supply and security is essential for managing this global crisis, and for vastly improving management of all water resources for the generations to come,” he writes in an article published on October 29.

Two billion people use aquifers as a primary drinking water source, and groundwater accounts for roughly one-third of the world’s water withdrawals. The highest rates of groundwater depletion are in the world’s largest food-growing regions: California’s Central Valley, the Ogallala Aquifer of the American Great Plains, the plains of northern China and northwest India, as well as the Tigris and Euphrates River Basin.

The consequences of ignoring groundwater are severe, Famiglietti says. Because half of the water used for irrigation comes from underground, food production is at risk if water supply and demand are not balanced.

“Vanishing groundwater will translate into major declines in agricultural productivity and energy production, with the potential for skyrocketing food prices and profound economic and political ramifications,” he claims.

Responses Are Available

To address the crisis, Famiglietti offers five steps that require immediate action:

- Acknowledge that in many arid basins, demands far exceed supply. “The myth of limitless water and the free-for-all mentality that has pervaded groundwater use must now come to an end,” he writes. To begin closing that chasm, he recommends starting with agriculture, which accounts for 80 percent of the world’s water use, about half of which is from groundwater. Farmers can be more efficient with the supplies they have by using irrigation technologies that require less water and land -management practices that prevent soil moisture from evaporating.

- Fill knowledge gaps. Though it is such an important resource, little is known about the actual volumes of water underground. Calculations often amount to back-of-the-envelope estimates. Measurement of groundwater pollution is also missing.

- Manage rivers and aquifers as one system. Because the two are connected, rampant use of groundwater causes streams to run dry. Major rivers in the American Great Plains and Southwest U.S. are sandy channels where groundwater withdrawals are the highest. Conversely, too much water pulled from streams limits the water that is available to refill aquifers.

- Measure, report, and share water data. Without measurement, attempts at management are rendered blind.

- Put groundwater on the international political agenda. Water treaties between countries that share a river basin are common, Famiglietti notes. But treaties to define and divide groundwater resources are rare. The United Nations reckons that 448 aquifers cross political boundaries – a number that continues to rise as more studies are completed.

The consequences of inaction are stark, Famiglietti asserts.

“Further declines in groundwater availability may well trigger more civil uprising and international violent conflict in the already water-stressed regions of the world, and new conflict in others,” he writes. “From North Africa to the Middle East to South Asia, regions where it is already common to drill over 2 km to reach groundwater, it is highly likely that disappearing groundwater could act as a flashpoint for conflict.”

Scientists are ringing these alarm bells with greater frequency. A year ago, the National Research Council, an arm of the most prestigious scientific body in the United States, argued that groundwater is a fraying safety net.

As reserves fall, society will find responding to droughts and shifting weather patterns all the more difficult. It is now up to the politicians and managers to heed the warnings.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!