California Lawmakers Move to Protect the State’s Collapsing Groundwater Supply

New rules seek sustainable use, but the details will be written later by local agencies.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

The worst drought in state history, a drought so deep that water supplies have never been lower, is prodding California lawmakers to tighten control of a valuable yet largely unregulated resource: its groundwater reserves.

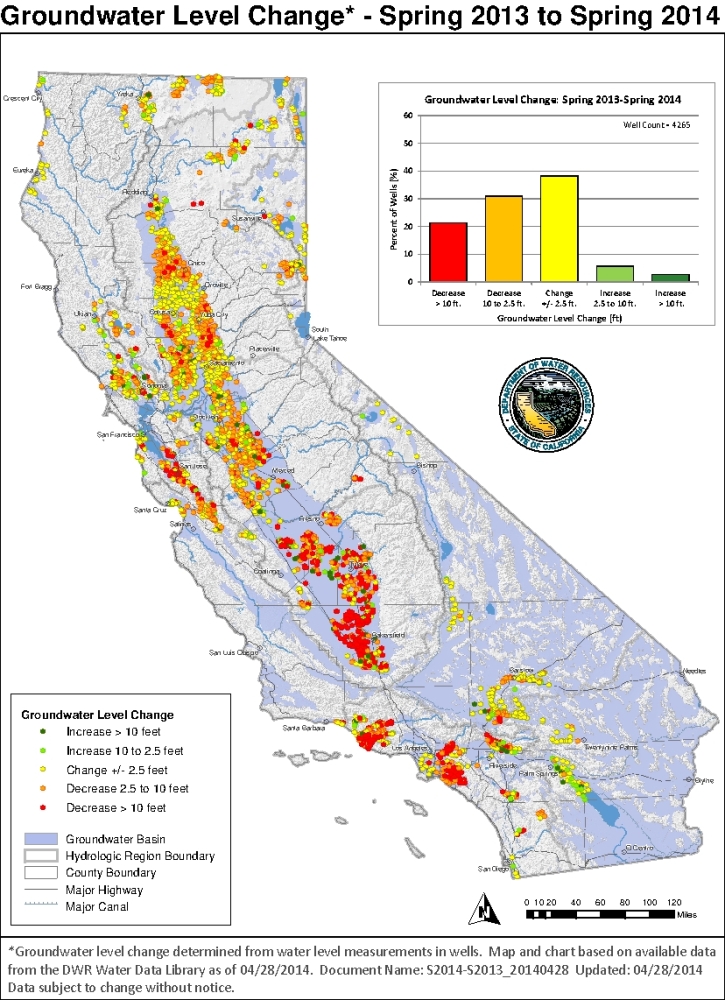

Commonplace in most other Western U.S. states, rules about who can drill a well and how much water can be pumped are rare in California, which has no comprehensive code for managing groundwater. This year, that policy gap has led to a resource free-for-all in which a record number of wells are going dry and water tables are dropping as much as two meters (six feet) per week in parts of the San Joaquin Valley, a key farming region.

The new rules, expected to pass the legislature within the next week, require local land and water agencies to develop management plans that will arrest a striking collapse of the state’s aquifers. In charge of enforcement and monitoring as well, local agencies must also consider in their plans how groundwater use affects the concentration of pollutants in water bodies, the subsurface flow of water into rivers, and the stability of the land surface, which can collapse if too much groundwater is pumped.

–Roger Dickinson,

California assemblyman

Similar bills in both legislative chambers were moved out of committee last week and will be ready for a floor vote as soon as Thursday or Friday after a second round of amendments, according to Roger Dickinson (D), sponsor of Assembly Bill 1739.

Though a milestone, legislative approval is not an end point. Lawmakers are developing a vehicle for groundwater management and putting local agencies in the driver’s seat, but the destination is not yet clearly marked. Many of the goals of groundwater reform – most notably the idea of “sustainable use” – are vaguely defined in the bills, as are the thresholds at which the state would step in to manage a basin if local performance is deemed unsatisfactory.

Dickinson told Circle of Blue that the legislation is “a template for governance” and that bureaucrats will work out the details later.

“The Department of Water Resources will develop guidelines to assist local agencies,” Dickinson said. “It is reasonable to expect that the guidelines would spell out what is meant by ‘sustainable.’ We’re not going to get that prescriptive in the bill.”

The Need for Action

Though state agencies will have until June 2016 to develop the definitions, the need for action is urgent.

The drought, now in its third year, represents the largest-ever reduction in water availability for California’s farmers, according to researchers at the University of California, Davis. Agriculture accounts for roughly 80 percent of the state’s water use, most of which is coming from the ground.

“We’re in danger of depleting our groundwater to such an extent that we could find ourselves in a disastrous situation in the future with respect to groundwater availability,” Dickinson told Circle of Blue. Nearly all the state’s groundwater basins are at historic lows, some more than 30 meters (100 feet) below previous records.

With a pitiful trickle of water coming through the canals, farmers are turning en masse to groundwater to make up the deficit. A few dozen basins, most in southern California, are regulated through a court process known as adjudication. A handful of others levy fees on the volume of water pumped, an economic brake on overuse. But in many farming regions, where water use is highest, groundwater is essentially a public good that any farmer with a deep enough well is free to tap.

The prodigious collective gulp the farmers are taking from the aquifers is causing harm beyond the field. Shallow residential wells are drying up while the land surface is shrinking, causing common infrastructure – such as canals – to buckle. Pollutants such as arsenic and nitrates are becoming more concentrated, leading to poorer quality water. Moreover, the cost of pumping that water is rising, adding at least $US 454 million to farm expenses this year, by one estimate.

All of which has led to widespread recognition that the tradition of unfettered access to the aquifers must be tossed out. Commissioned by two groups focused on groundwater reform, public opinion polling last month found that 78 percent of respondents supported the basic framework that has been proposed in the state capitol.

“Current groundwater practices cannot continue. They have to be addressed,” said Dave Smith, general manager of Booth Ranches, an orange grower based in eastern Fresno County. Referring to the act of pumping out more water than soaks into the ground, Smith continued, “Groundwater regulations have to happen because we’re overdrafting. We can’t let everyone stick a straw in and hope that it will work out.”

Developing A Framework

The legislation will force the soft hand of local agencies. It requires the 127 groundwater basins with the highest water use and largest populations to take control of their resource. (The 23 basins adjudicated basins are exempted from the process.)

A $US 7.5 billion water spending package, signed by Governor Jerry Brown (D) last week, offers $US 100 million to help basins develop groundwater-management plans. If approved by voters in November, the money would be available beginning next year.

Local land and water officials will have until 2017 to form a management agency. By 2020, the agency must submit a plan for addressing a host of groundwater issues: monitoring water levels and water quality, preventing the inland push of saltwater in coastal areas, and collecting data. The plans will explain how overdraft will be halted and will plot the areas where water most easily filters into the aquifer, in order to guide land-use decisions. A basin will have two decades to meet the objectives in its plan, and all basins would be eligible for potential funds from Brown’s package.

Cobbling together a new management agency will require unprecedented cooperation between California’s fragmented legal jurisdictions. Counties and cities – usually in charge of building permits and land use – must collaborate with water utilities, canal managers, and irrigators.

“The act is going to require all entities to come together and form a single plan,” David Orth, general manager of the Kings River Conservation District, told Circle of Blue. Orth represented the Association of California Water Agencies, a trade group for water providers, in negotiations over the groundwater bill.

Obstructions

Forming a big-tent coalition presents its own challenges, one of which is currently on display in San Luis Obispo County on the central coast. Attempts to set up an agency there to manage a declining aquifer have stalled as large landowners and small landowners cannot agree on how to distribute voting shares.

The mix of voices that will guide a new agency is also a concern for the Community Water Center, a nonprofit in the San Joaquin Valley that helps poor and minority communities get clean drinking water.

“We’re cautious about how the groundwater-management law might be implemented,” said Maria Herrera, community advocacy director, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “We want to safeguard seats so that any agency is not an entity, driven by irrigation districts and the counties – the drought proves that those hardest hit are the individuals.”

Questions about equity take other forms as well.

Smith, general manager of Booth Ranches, wonders how seniority might be handled. Would the newest wells face a different set of rules and restrictions?

“I didn’t overdraft by myself,” he mused. “But if I’ve got 30 years of history and my neighbor has six months, how is that addressed? The mechanics of the law – how do you actually do it? It’s very complex.”

The legislation provides little direction. It sets minimum standards but delegates the substance to local leaders. Once the law is passed, those communities where a management plan is required will have plenty to discuss.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!