Big Investment Updates Great Lakes Shipping

New technology and ships make maritime commerce more efficient, adaptable, and environmentally friendly.

Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

The Algoma Equinox slid into the water for the first time at a shipyard in Nantong, China, on December 24, 2012. The 225-meter (740-foot) freighter was destined for the Great Lakes, an early participant in the mid-continent shipping industry’s biggest upgrade in half a century.

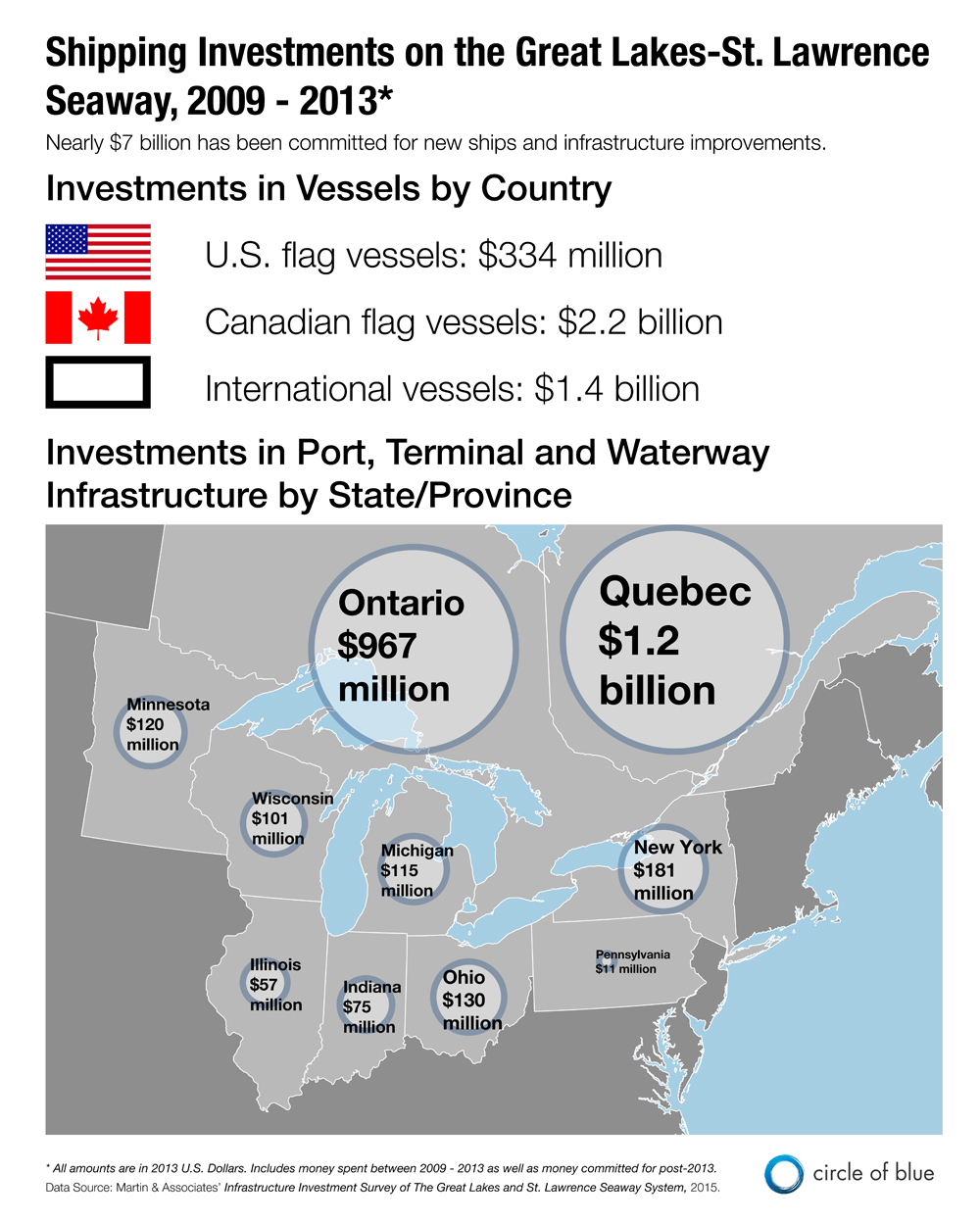

Over the past five years, private companies and governments in the Great Lakes region have committed $US 7 billion to build new ships, improve port infrastructure, and update locks and breakwaters along the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway, according to an industry survey released this year by the Chamber of Marine Commerce in Ottawa.

Made in response to an aging fleet, more stringent environmental regulations, and an increasingly global economy, the investment is shaping the course of Great Lakes shipping for the next 30 to 40 years. At the same time, advancements in technology are providing ship captains and navigators with an increasingly accurate view of shipping channels, allowing them to navigate the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River system with more precision. In combination, the developments mean more cargo can be moved with less fuel, fewer emissions, and in shallower water.

It is the largest infusion of money into Great Lakes shipping since the construction of the modern St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s, according to Stephen Brooks, president of the Chamber of Marine Commerce. The Seaway project cost a total of $US 470 million—equivalent to about $US 4.6 billion today. Most of it was financed by Canada. Together with the Welland Canal that circumnavigates Niagara Falls, and the Soo Locks that enable passage between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, the navigation system allows ships to travel 3,700-kilometers (2,300 miles) from Duluth, Minnesota, to the Atlantic Ocean at Sept-Iles, Quebec. Every year, vessels transiting the system carry about 164 million metric tons of cargo including bulk shipments of iron ore, road salt, corn, and wheat, as well as specialized products like wine, furniture, and clothing from all over the world.

“[The investment] really is quite unprecedented,” Brooks told Circle of Blue. “And I think it’s important to keep that perspective, that this is something we may not see again in many of our lives, this level of investment.”

New Ships Bolster Aging Fleet

The vast majority of the money being spent—nearly $US 4 billion—is funding new ships. For years, the industry in Canada was hamstringed by a 25 percent import duty on ships purchased abroad, according to Brooks. When that was lifted in 2010, companies began investing heavily in their fleets.

“Up until 2009, the fleet of Canadian ships in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence region had reached an average age of 35 years, which is quite old for these ships. Old certainly in terms of their technology. Old in terms of efficiency. And old in terms of their ability to comply with increasingly stringent environmental regulations,” Brooks said. “The industry was at quite a critical crossroads. In order to continue and be sustainable, and to provide the valuable services that these ships provide for both North American industry and people around the world, they had to figure out a way to get new ships.”

The St. Catharines, Ontario-based Algoma Central Corporation, the largest ship owner and operator on the Great Lakes, has announced 9 new ships since 2009. Three are already operating on the lakes, while the others are expected to be in service by 2018.

“The older ships were much more expensive to maintain to high Canadian standards,” Wayne Smith, senior vice president of commercial for Algoma, told Circle of Blue. “We made the decision back in 2009, 2010 that we had to renew our fleet. We spent a couple years really trying to develop what we thought would be the best, or optimal, design for the future, next generation of Great Lakes vessels.”

The company’s new Equinox Class ships are generally larger than their old carriers, with most reaching 225.5 meters (740 feet) in length and 23.8 meters (78 feet) in beam, the maximum dimensions for a ship to fit through the St. Lawrence Seaway. They have integrated exhaust scrubber systems that remove 97 percent of sulfur oxide and 75 percent of particulate matter emissions, resulting in an overall 40 percent reduction in air emissions compared to the older ships. In addition, larger propellers turned by slower engines as well as smoother hull coatings improve the ships’ fuel efficiency, said Smith.

“The new designs are a lot more efficient in terms of fuel, the emissions are scrubbed, and they’re carrying more,” he said.

“It’s been challenging since the recession in 2008 and 2009 for businesses to recover to pre-recession levels, and we’re still working with all of our customers to try to get to those levels,” Smith added. “The new ships are essentially viable and finance themselves because of improved efficiency.”

Carrying More, Even in Shallow Water

Even as ships traveling the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River get bigger, new technology is allowing them to carry more through the shallowest parts of the Seaway. In 2012, Canadian and U.S.-flagged ships began using a tool called the Draft Information System (DIS), which gives captains and pilots a precise view of the surrounding channel and allows them to navigate more safely.

The more cargo a ship carries, the lower it sits in the water. The distance a ship’s hull extends below the water’s surface is called its draft, and when a ship travels faster, its draft increases. When it travels slower, its draft decreases. That means that a large ship carrying lots of cargo needs to slow down to cross through shallow areas. But without a good idea of where shallow areas are located in relation to the ship or how the ship’s draft changes at different speeds, navigators must carry less to give themselves a wider margin of error.

In the St. Lawrence Seaway, most ships are required to travel with a draft of 8.07 meters (26 feet and 6 inches) or less. DIS, however, provides navigators with detailed, color-coded hydrographic maps of the Seaway that track the ship’s location and speed and show which areas to avoid and which areas are safe. As a result, ships equipped with DIS can travel with a maximum draft of 8.15 meters (26 feet and 9 inches)—a difference that allows the biggest ships on the Seaway to carry an extra 400 metric tons of cargo.

“Those tons can be transported without any meaningful increase in fuel consumption,” Andrew Bogora, communications and public relations officer for the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation, told Circle of Blue. “That not only gives substantial benefits to the ship operator, but in terms of fuel efficiency it can reduce emissions. So your carbon footprint per ton of cargo keeps dropping as you become more efficient.”

Even in the rare cases when water levels drop to the point where Seaway managers have to reduce the permissible draft, ships with DIS will be able to travel with 7.6 more centimeters (3 inches) of draft than those without it, Bogora said. Currently 30 ships in the domestic fleet have the technology.

“Rather than presenting the water, the riverbed, as flat as a dance floor, we are now actually using the full water column,” Daniel Dagenais, vice president of operations at the Port of Montreal, told Circle of Blue. “So what we are trying to do is integrate that. Before, even though people knew intuitively that a river was not like a dance floor, they couldn’t have the information because it was constantly changing because of sedimentation, because of ebb and flow, tide movements in the bottom of the St. Lawrence River.”

“Before, it was kind of a lobotomized process because there was just so much margin on top, above—no one really cared,” he added. “But as the resource is getting scarcer and scarcer, then we need to better manage this resource—the water.”

Seaway Ports Adapt Too

Ports along the Seaway are also investing in facility improvements and benefiting from technological advances. The Port of Montreal, for example, is now using a system that allows it to inspect the river and underwater portions of its facilities, such as berth walls, in two days; the process took years in the past. In 2014, it spent $US 20.5 million upgrading and expanding its container handling areas and ship berths and announced a $US 59 million project to restore a historic pier and passenger terminal for cruise ships.

“For us, we are a facilitator for the movement of goods, and we always need to keep an eye out on marine access—draft, width, winter navigation and the pilotage cost, and all of that,” Dagenais said. “But we also have to keep an eye out on the shore side as well because connectivity is king in this particular business.”

The port’s business is growing. A record 30.4 million metric tons of cargo passed through its facilities in 2014, as well as more than 71,000 cruise passengers. One of its biggest challenges, according to Dagenais, is visibility in an increasingly global market shaped by shifting economic centers. In 2000, nearly 80 percent of the port’s overseas trade was with northern Europe. By 2013, Europe’s share dropped to 44 percent.

“Some of the challenges we have faced have been there for a long time, but as the emerging markets are coming along, then it’s no longer the countries that actually colonized this continent that we are dealing with—it’s people who don’t know Montreal at all or don’t know the geography of the land,” Dagenais said. “So you know what, there’s more education to be done. So that’s why we actually have technology here to manage the river, but also people in Hong Kong, we have people in Europe, people traveling all over the Middle East, to make sure that they are made aware that Montreal is a possible market for them to ship their goods.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!