Getting Off the Pipe

At the end of the 400-mile-long California Aqueduct lies a sea of concrete, the sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles. To get here, water from the Delta must not only travel a great distance, but must be pumped nearly 2,000 feet over the Tehachapi Mountains to arrive at the taps of Los Angeles’s roughly 20 million consumers.

In the world of water engineering, distance equals vulnerability.

Because Los Angeles’s water travels the greatest distance and elevation to arrive here, water users in the Los Angeles Basin also pay the highest rates in the State Water Project system. Many refer to the price discrepancies as a “subsidy,” and in many ways it appears that is the case. It’s not uncommon for water districts to pay five to ten times more per acre-foot than farmers in the Central Valley.

Roughly half of the water used by the city of Los Angeles comes from the State Water Project and Colorado River. But the California Aqueduct is by no means the only long-distance water conveyance system feeding Los Angeles. Another 35 percent of the city’s water comes from the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Built in 1913 at the behest of infamous water department superintendent and power broker William Mulholland, the aqueduct is among the most controversial water engineering projects of its time, prompted Chinatown, a famous 1974 movie that described how it siphoned water from Owens Lake, and decimated the picturesque Mono Lake and the Owens River Valley in the process.

Several cities in the Los Angeles metro area have recognized the region’s precarious position in the state’s water delivery system and have begun to take steps to reduce their dependency on water delivered from the SWP.

The city of Santa Monica is looking to eliminate use of water imported from the Bay Delta and Colorado River entirely by 2020. In addition to wastewater recycling and rainwater capture, Santa Monica has begun remediating groundwater sources and now meets roughly 70 percent of its demand from wells.

Other cities are looking at efficiency measures. Long Beach, for example, is paying residents $3 per square foot to eliminate lawns in favor of xeriscaped gardens. Through this and other water-saving initiatives, the city has cut its per capita water use from 167 gallons in 1980 to 110 gallons in 2010, according to the National Resources Defense Council.

Some are looking at engineering-heavy solutions. Camarillo, an hour north of downtown Los Angeles, is moving ahead with plans to build a desalination plant to remove salt and other agricultural contaminants from its aquifers. City officials say use of local groundwater will reduce the city’s water imports from roughly 50 percent today to a mere 7 percent by 2035.

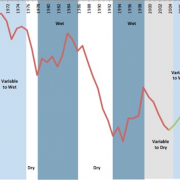

As persistent drought and population growth continue to challenge the state’s engineered water systems, more cities in the L.A. Metro Area will surely follow suit, looking for local solutions to eliminate the uncertainty and cost of being at the end of the pipe.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!