New Jersey Sets First Binding State Limits for Perfluorinated Chemicals in Drinking Water

Regulators adopt strictest standards in the nation.

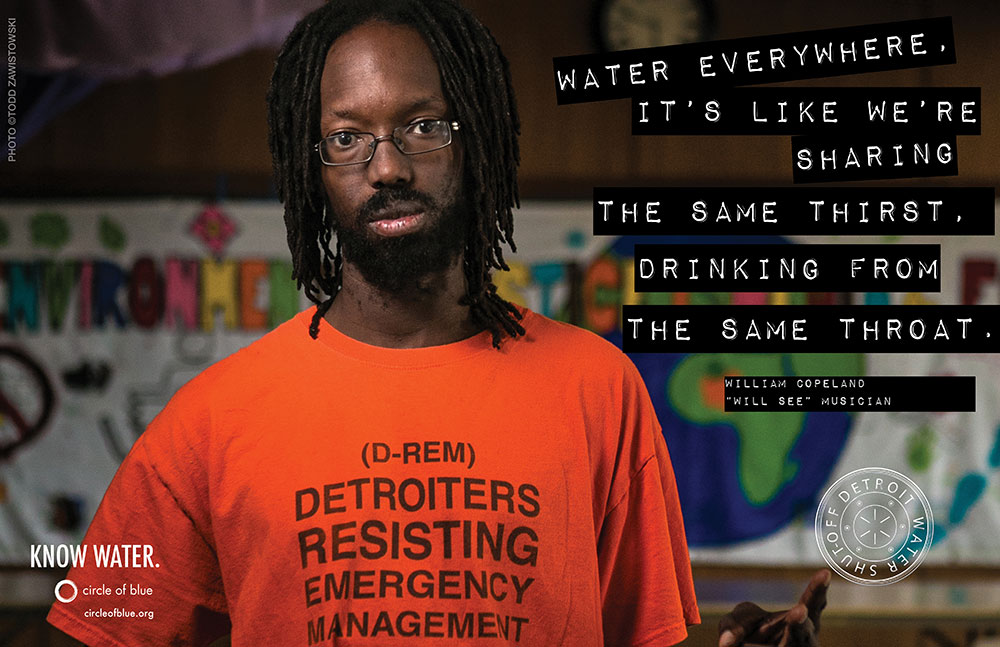

Groundwater in Salem County, New Jersey, has been contaminated by perfluorinated chemicals from industrial manufacturing facilities. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Besides lead, no contaminant in drinking water has provoked as loud a public outcry in the last two years in the United States as a class of chemicals known as perfluorinated compounds.

New Jersey regulators are taking the strongest action to date on the man-made chemicals that are used in scores of household and industrial products. The state will be the first to require utilities to test for two compounds and remove them from drinking water.

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection announced on November 1 that it accepted a recommendation from state water quality experts to set a legal limit for PFOA of 14 parts per trillion. The announcement follows a proposal in August to allow drinking water to contain no more than 13 parts per trillion of PFNA, a related perfluorinated compound used at plastics manufacturing facilities in New Jersey and found in public water systems.

Used in plastics production, firefighting foams, nonstick cookware, water-repelling clothing, food wrappers, and more, perfluorinated chemicals, of which there are dozens, are tenacious and ubiquitous in consumer products and water — and even in human bodies, where they are associated with high cholesterol, kidney cancer, liver damage, and thyroid disease.

In May 2016, the EPA strengthened its health advisory for two such chemicals, lowering the recommendation for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water from 400 parts per trillion to 70 parts per trillion combined. Because health advisories are a guideline and not a legally enforceable standard, the change set off a wave of confusion among state and local regulators. What, utility directors wondered, should they tell worried residents? Should they treat water so that PFOA and PFOS were below the new guidance, even if they were not required to?

A utility in Alabama whose water tested above the lower EPA threshold immediately told residents not to drink the water until it could bring down contaminant levels. A number of states then responded with their own advisories, often lower than the federal guideline.

“We’re being proactive and conservative because we’re aware that this is a growing national concern,” Larry Hajna, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection spokesman, told Circle of Blue.

The New Jersey rule will apply to some 582 water utilities in the state and 738 schools, churches, hospitals, and factories that operate their own drinking water systems.

Jeff Kray, an attorney at Marten Law, a firm that specializes in environmental law, has been tracking state responses to perfluorinated chemicals. At least a dozen states have taken steps since the EPA’s health advisory announcement to develop their own guidelines or to regulate these compounds in drinking water, groundwater, or at contaminated sites.

“The public is worried about what’s in the water, and water suppliers are concerned that they be able to tell people that their water is safe,” Kray told Circle of Blue.

The Pennsylvania Environmental Quality Board accepted a petition in August from Delaware Riverkeeper to investigate whether the state should set a standard for drinking water. The Washington Department of Health, meanwhile, is leading the development of a state response plan for perfluorinated compounds. Washington is on the same regulatory path as New Jersey and will likely end up with a drinking water standard, Kray said.

Regulators Draw Different Lines

New Jersey’s standards were developed by the state’s Drinking Water Quality Institute, a 15-member body established in 1984. Members are drawn from state public health officials and environmental scientists as well as independent experts appointed by the governor and Legislature.

New Jersey’s 14 parts per trillion benchmark for PFOA is lower than the EPA health advisory and lower than advisories in Minnesota (35 parts per trillion) and Vermont (20 parts per trillion). Keith Cooper, a toxicology professor at Rutgers University and a member of the Drinking Water Quality Institute, said the range of values is attributed to “subtle differences” in how risk assessments are carried out.

States might base their analysis on different academic studies or focus on different health outcomes. The Drinking Water Quality Institute based its analysis on rodent studies that assessed changes to the liver from PFOA and PFNA exposure.

States might also tolerate different levels of risk. New Jersey’s drinking water law requires that standards reduce the risk of cancer to one-in-a-million from a lifetime, or 70 years, of exposure.

“In New Jersey, we want to protect the most sensitive population over an entire lifetime,” Cooper told Circle of Blue.

Testing over the last decade showed that PFOA was present in roughly three dozen New Jersey water systems. PFNA was detected in about a dozen more, mostly in Gloucester County, where Solvay Polymers, a manufacturing facility, used the compound until 2010, and in neighboring Salem County.

Hajna, the department spokesman, said that detection does not mean that water delivered to customers has high PFNA or PFOA levels. Utilities have shut down affected wells or blended tainted water with cleaner sources to bring down concentrations. Chemours, one of the companies responsible for contamination in Salem County, has installed treatment systems at homes whose wells were affected.

New Jersey will soon consider regulating a third perfluorinated compound in drinking water. The Drinking Water Quality Institute is conducting a risk assessment for PFOS. Cooper said a recommendation for a health standard will be ready in roughly a year.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton