On February 1, 2018, Cape Town clamped down on water usage, harder than any other city with its living standards. Officials set a target of 50 liters (13 gallons) per person per day for all domestic uses: cooking, bathing, toilet flushing, washing clothes. Residents formed long queues to fill bottles at Newlands Spring. Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

What does water panic look like in a major global city? Cape Town’s Day Zero crisis. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

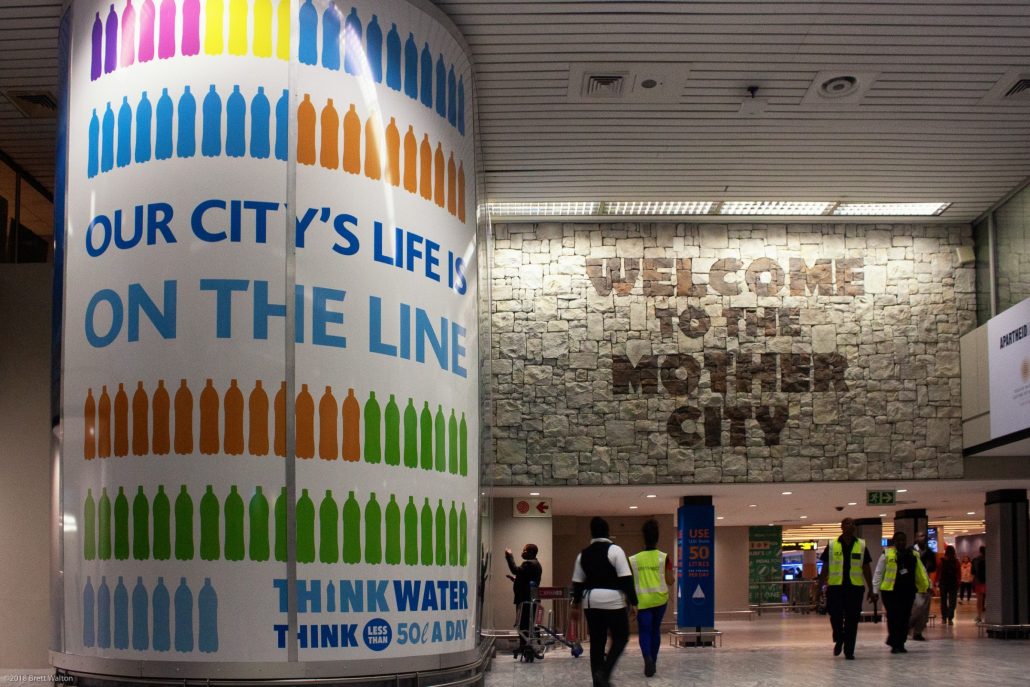

Signs warn visitors arriving at the Cape Town airport of the city’s water crisis, dubbed Day Zero, the day when water stored in the city’s six main reservoirs would drop below 13.5 percent of capacity. If that had happened, city officials warned that they would shut off water to most homes and businesses. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Severe supply restrictions instituted on agriculture and city dwellers alike, and a heroic, last-ditch conservation effort halted the swift drop in reservoir levels which more than doubled in June and July as the wet season arrived. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Many farmers like Barend Vorster, had to let go of their vines because of the drought. Farmers in the Western Cape of South Africa had already been badly affected by dry conditions which started in 2015. This year farmers in the Vredendal area were restricted to 14 percent of their normal water use. As a result, many removed vineyards or let them die. Consequently, harvests were smaller and there was less work for seasonal workers. At the end of February, the farm sector, which was allocated one-third of the water from the Western Cape system, reached its limit. With farms not drawing from the reservoirs anymore, the pace of decline slowed, further delaying Day Zero for Cape Town. Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

Cape Town’s water crisis exposed the inadequacies of institutions, laws, and leadership to recognize and respond quickly enough to severe water shortages. Local, provincial, and national authorities were aware of the water supply system’s weaknesses, and had plans to address them. After more than a decade of planning, however, they determined that they could delay the date at which they needed to invest in new water supplies. As it turns out, they waited too long. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

A day after Mayor De Lille’s Day Zero announcement, the city council revoked her responsibility to oversee the drought response owing to unrelated charges from her party of mismanagement and corruption. In the depths of the Day Zero panic, politicians started pointing fingers. While politics and mismanagement rose to the stage, the shrinking water levels in Theewaterskloof Dam, the largest in the Western Cape Water Supply System and Cape Town’s main source of water, revealed long-dead trees and dusty plains in 2018. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Hopes of a “quick win” — rapidly boosting supply from a fleet of small-scale desalination plants — proved to be illusory after consultation with World Bank experts, said Ian Neilson, the deputy mayor. Acquiring, delivering, and installing the plants would have been too expensive, too slow, and useless over the long-term because the cost per unit of water was so high. The only response the city could muster in the short term was to drive down water use. Businesses along the V&A Waterfront advertise their use of desalinated water, so as not to be dependent on the city’s supply. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Deputy Mayor Ian Neilson grounded his response to Day Zero by supplying residents and businesses with as much information as possible on dam levels, water consumption, and the progress of water infrastructure projects. “We have to keep the message up. We have to keep them on board. The only way I see that can be achieved is that we have to be open and frank and truthful.” Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

The law enforcement department stepped up its policing of water waste in January, when the water crisis reached a crescendo. Police here crack down on illegal water usage in Khayelitsha — an informal township located on the Cape Flats in the City of Cape Town. In this case car wash operators in Khayalitsha fled before law enforcement could catch and fine them for misusing municipal water. Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

The city took steps to constrict residents’ water use if they couldn’t adhere to restrictions on their own. Between October 2017 and May 2018, city workers installed more than 46,170 “water management devices” that throttled the flow of water into homes that used more than 10,500 liters a month. Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

Panic surrounding Day Zero was not evenly distributed in this economically divided city. Some 12 percent of households — those on the periphery of the city in what are called informal settlements which are largely home to poor black residents — have always had to collect water from a community well. Day Zero, however, presented a crisis for the middle and upper classes who were generally unaccustomed to such deprivation. Meanwhile, wealthier city residents who could afford to, drilled boreholes on their property to access groundwater privately. Officers from the Cape Town law enforcement department warn a homeowner in the Wynberg district that he needs proper signage on his property that his borehole is registered with the city. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

The drought touched all aspects of life in Cape Town and the surrounding region. An estimated 7,000 farm jobs were lost in the first quarter of 2018 compared to a year earlier, and the wine harvest dropped 15 percent. The tourism sector, was also pummeled with bookings down 10 to 15 percent during the summer. Because pools were drained and unwatered rugby pitches had the cushioning of a sidewalk, recreational options for Capetonians were limited. Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

Students at LEAP, a private school in the Philippi district of Cape Town, walk between buildings during a class break. Starting in February water at the school occasionally stopped flowing and the school had to cancel classes. “If there’s no water on site, school can’t run,” said Nasreen Abrams, a school leader. “It’s affected us in a big way.”Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

At a construction site in the Woodstock district of Cape Town, a building contractor had to dispose of a steady flow of groundwater that arose in the basement. Isipani Construction made the non-potable water available to the public through these taps. Eben Beaurain, who manages water logistics for Isipani, said that knowledge of the taps spread by word of mouth. “A few people came, and then more came,” Beaurain said, recalling that lines extended around the block in January and February, at the height of the crisis. People lined up until midnight, he said. Photo © Morgana Wingard/Getty Images

Cape Town’s Day Zero water crisis has been averted for this year thanks to a wet start to the rainy season. In the meantime, the city is investigating three steps to diversify its water supply: 1) Drilling for groundwater 2) Reusing waste water 3) Building desalination plants. Although a large desalination plant could produce between 120 million to 150 million liters of water a day, Christine Colvin, a freshwater specialist with WWF South Africa says, “desalination is the biggest carbon footprint of water and biggest cost of water.” Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Cape Town’s Harrowing Journey to the Brink of Water Catastrophe

Six months ago Cape Town was a city on edge. The mayor had declared that Day Zero, when officials would shut off water to most homes and businesses in order to preserve fast-shrinking reservoirs, was imminent. Police began to ticket individuals for washing taxis, watering lawns, or otherwise wasting water.

Residents responded to the panicked messages from City Hall with their own panic. They queued for hours to fill bottles at local springs. They hoarded water. They took showers while standing in buckets and rejiggered their home plumbing to reuse water from laundry machines.

By July, Cape Town looks to have evaded a water catastrophe, at least for this year. Residents are using substantially less water. Severe water supply restrictions instituted on agriculture and city dwellers alike, and a heroic, last-ditch conservation effort halted the swift drop in reservoir levels. Winter rains are now providing some relief. The amount of water stored in the reservoirs more than doubled in the last month and rivers in the Western Cape swelled in downpours. Snow graced the mountain peaks. The start of the wet season this year is more promising than any of the last three.

The near-death experience, though, is revealing for the gorgeous seaside city at the southern tip of Africa. And it offers lessons in the immense challenges fast-growing and drought-prone cities all over the world face in making adequate supplies of water available in the era of intensifying hydrological disruption. Other big cities also contend with severe water shortages, some that prompt civic violence. They include Beijing and São Paulo; Chennai, New Delhi, and Bangalore in India; Karachi, Amman, and Mexico City.

The Western Cape drought and the subsequent receding of Cape Town’s reservoirs exposed individuals and businesses to months of hardship and anguish. It laid bare the inadequacies of institutions, laws, and leadership to recognize and respond quickly enough to severe water shortage. The drought magnified the city’s racial and economic divides, which are legacies of apartheid.

It also unveiled the precarious risk calculations that local and national authorities charged with safeguarding Cape Town from just such an emergency had to make. Those authorities and their agencies have been aware for years of vulnerabilities in the Western Cape water system. They even drew up careful plans to address weaknesses. Yet after more than a decade of planning, and regular meetings to discuss drought-related risks, they determined that they could keep delaying the date at which they needed to invest in new water supplies. As it turns out, they waited too long. Severe drought took hold and the Cape Town region slid to the brink of catastrophe.

Read the full story at Circle of Blue.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton