Environmental factors are the most devastating risks to business and society and the most likely, report says.

In the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, women transplant rice in a field that is irrigated with industrial wastewater pumped from a nearby canal. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

- Global risks are intensifying but the collective will to tackle them appears to be lacking

- Drought, water scarcity, climate change, extreme weather are among the biggest risks to society and industry

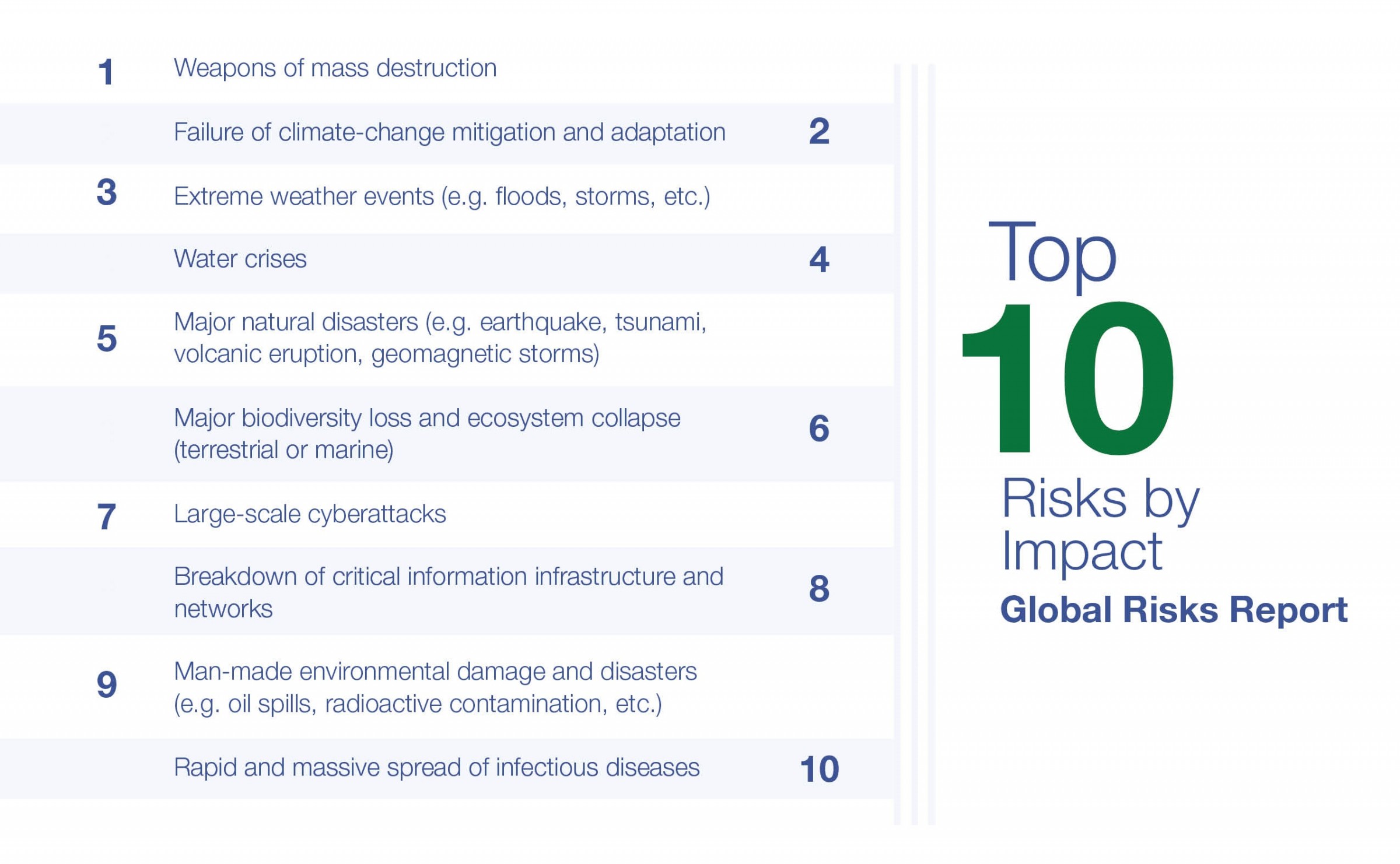

- Water crises were a top-five most damaging risk for the eighth consecutive year

- Groundwater depletion, drought, population growth, poor management, and inadequate infrastructure development are all factors of risk of water shortages for major cities

In India, Pakistan, Guatemala, and other countries where drought rakes deep and social safety nets are thin, farmers are fleeing the desperation of failed harvests to move to cities or join caravans across national borders.

In northern Europe last year, drought dropped the level of the Rhine River, a key transport artery, to record-low levels. Barges had to be halted and shipments of diesel fuel upstream were pinched.

And just this week, Pacific Gas and Electric, California’s largest power utility, said it will file for bankruptcy as it faces billions of dollars in claims for the role its power lines allegedly played in sparking recent wildfires including the Camp Fire, a hellish conflagration in November 2018 in the Sierra Nevada foothills that killed 86 people and destroyed the town of Paradise.

Global risks are intensifying but the collective will to tackle them appears to be lacking.”

Drought, water scarcity, climate change, extreme weather — these and other environmental factors are among the biggest risks to society and industry, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report, an annual survey of nearly 1,000 leaders in business, government, academia, and international organizations.

The fourteenth edition of the report comes amid warnings that the planet’s convulsions are strengthening — and that leaders may not be backing their expressions of concern with appropriate action.

A United Nations climate change report published in October noted that earlier projections of the pace of warming and environmental change were too conservative. The UN also reported last year that carbon emissions rose in 2017 and countries are neither on track to avoid two degrees Celsius of warming, nor to meet the Sustainable Development Goals for water and sanitation. Those goals envision safe and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all by 2030.

“Global risks are intensifying but the collective will to tackle them appears to be lacking,” the report states. “Instead, divisions are hardening.”

The World Economic Forum asked its members and professional networks to rate 30 global risks based on two attributes: the likelihood that they will occur within the next decade and the damage they will cause. These risks include economic variables such as inflation or high national debt, geopolitical variables like war and terrorist attacks, and “societal” risks such as food crises, migration, and disease outbreaks.

For the third consecutive year, weapons of mass destruction ranked as the most damaging risk, but also the least likely.

Each of the five environmental risks listed in the survey — extreme weather, failure to respond to climate change, biodiversity loss/ecosystem degradation, natural disasters, and manmade environmental disasters such as an oil spill — is rated as both highly likely and highly damaging. Water crises, categorized as a societal risk because of their far-reaching consequences, also rated as highly likely and highly damaging. It is the eighth consecutive year that water crises were a top-five most damaging risk.

“The results are quite consistent for the last few years,” Eugenie Molyneux, chief risk officer at Zurich Insurance Group, told Circle of Blue. “Environmental risks are near the top of the survey for their impact.”

Climate change, as the world is coming to realize, is only partly about polar bears and glaciers. It’s also about human health and business viability and not having the highway turn into taffy from extreme heat. It’s about being able to work outside and not die from heat stroke.

The report threads these connections. Special sections examine more deeply how risks intersect and interact. A section on sea level rise links the increasing demand for water in megacities like Jakarta with accelerated inundation. Indonesia’s capital, a coastal city of more than 10 million people, pumps more groundwater than is sustainable. As it does, the land sinks, magnifying the risk from rising seas and storm surges.

The report warns that leaders are not prepared for migrations away from coastal areas.

“More people will be crammed into shrinking tracts of habitable urban space, and more are likely to move to other cities, either domestically or in other countries,” the report states. “These movements have the potential to cause spillover risks — for example, they could result in heightened strain on food and water supplies and in increased societal, economic, and even security pressures.”

Another section ponders “future shocks” — meaning rapid and destabilizing changes. These scenarios, often the domain of science fiction writers, are speculative but nonetheless plausible outcomes given the trajectory of politics, technology, and environmental change.

Molyneux, who advised on the topics that went into the report, said that the future shocks sections provide “food for thought” for leaders to think creatively about potential risks.

One scenario sketched in the report is weather wars. Seeding clouds with particles to induce rainfall has occurred for decades. But today the stakes are higher. Better scientific knowledge can pinpoint the upstream source of weather and rainfall. Might one government accuse a neighbor of “stealing” its rain?

Another scenario, influenced by the crisis last year in Cape Town, is water shortages in major cities. Groundwater depletion, drought, population growth, poor management, and inadequate infrastructure development are all factors.

Many companies are taking action to prepare for environmental shocks, but their focus is often narrow, Molyneux explained. “They are thinking about adaptation strategies, but not mitigation. And they are thinking about direct risks but not interconnected risks,” she said. A direct risk might be damage to a production facility from flooding, whereas an interconnected risk would be sufficient water supply for the community in which they operate.

“The issues are often broader than the actions one company would take,” Molyneux said.

The people who filled out the survey that underpins the risks report are demographically similar to the cohort from previous years.

Less than a quarter of the 916 respondents who shared biographical information are under age 40. Nearly three-quarters are men and nearly two-thirds of respondents are from Europe or North America, both figures being comparable to last year. A third of respondents work in business. Fewer business executives answered the survey this year, whereas the number of government leaders who participated increased.

Why the World Economic Forum just named water among the world’s global risks. Learn more here:

India, the country that pumps more groundwater than any other has reached a water supply and food safety reckoning that threatens to upend political and economic stability, and long-term public health. Learn more.

Furious and fearful, residents are asking a simple but urgent question: what’s in my water? But PFAS are the tip of the spear for threats to groundwater in Michigan and nationally. Learn more.

In increasingly dry conditions, cities from Australia and the Middle East to the American Southwest are pursuing groundwater, either as an integral piece of their future water supply or as an emergency stopgap measure. Learn more.

Analysis demonstrates that fresh groundwater, in eastern states as well as those west of the Mississippi, is shallower than previously thought and thus less abundant. Learn more.

Jakarta — home to more than 10 million people and the capital of Indonesia, the largest economy in Southeast Asia — is sinking at an increasing rate. Learn more.

Drilling, fracking, and extracting crude oil and natural gas from shale requires prodigious volumes of water in the world-class energy fields in New Mexico, Texas, and five other Great Plains states that now supply almost 70 percent of the country’s 10.1 million-barrel-a-day production, the most ever. Learn more.

Panic. Residents in South Africa’s second largest city repeatedly used that word to describe the weeks after January 18 when Mayor Patricia De Lille proclaimed that the day the city would run out of water, what was called “Day Zero,” was fast approaching. The declaration hit like a blast wave. Learn more.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton