Perspective | Do Two Failed Dams Foretell a Dire Future?

It is possible that more dams will fail.

This aerial view from February 15, 2017, shows the damaged flood control spillway at Oroville Dam, in northern California. The California Department of Water Resources, which owns the dam, has since repaired the spillway, which failed in 2017. Photo Dale Kolke / California Department of Water Resources

Upmanu Lall and Paulina Concha Larrauri

Two more dams down, a few thousand more to go.

The failure of Edenville and Sanford dams last week after heavy rains was a narrow escape for Michigan. Luckily, no one died, but 10,000 people were evacuated. The massive flooding from the failed dams got close to a Superfund site and the Dow Chemical Complex. Fortunately, no toxics were mobilized. The disaster brought a Presidential emergency declaration, but once again there is little discussion of a growing hazard that we are ignoring — our aging and failing infrastructure.

It is possible that more dams will fail. The question to ask is what the state governments in the region are doing to deal with potential floods and dam breaks.”

The Detroit News reported in November 2019 that 19 dams in Michigan were rated as both high hazard and in unsatisfactory condition. The Edenville dam was rated as unsatisfactory and the Sanford dam was rated as fair. High hazard means that the dam’s failure could kill people downstream. Unsatisfactory and fair are comments on the dam’s structural quality.

The 2008 financial market crash was called a “black swan” event — an extreme catastrophic event that was not anticipated. We hope that when a catastrophic dam failure occurs in the United States it will not be called a black swan, since there is already strong evidence that the combination of aging and poorly maintained infrastructure and climate extremes could be very deadly.

Climate change is increasing the frequency of extreme rainfall events, hence the risk for filling and overtopping dams, which is the predominant mechanism of dam failure. However, using climate change as a bogeyman for aging infrastructure failure is an unfortunate trend since it takes attention away from an urgent and potentially fixable problem.

The federal government’s fourth National Climate Assessment, published in 2018, noted the risks.

“Aging and deteriorating dams and levees also represent an increasing hazard when exposed to extreme or, in some cases, even moderate rainfall,” the report stated. “Several recent heavy rainfall events have led to dam, levee, or critical infrastructure failures, including the Oroville emergency spillway in California in 2017, Missouri River levees in 2017, 50 dams in South Carolina in October 2015 and 25 more dams in the state in 2016, and New Orleans levees in 2005 and 2015. The national exposure to this risk has not yet been fully assessed.”

More recent failures heighten the concern: Spencer dam in Nebraska in 2019, the two Michigan dams, and a close call last week near Roanoke, Virginia. Dam failures are relatively rare, and despite their potentially catastrophic impacts, they seem not to get the attention that they deserve.

The near catastrophe at Oroville Dam in 2017 is a case in point. The failure of the dam’s spillways during a wet winter led to an evacuation of 180,000 people downstream. The wet conditions were anomalous, but not extreme. The flow over the emergency spillway, used that year for the first time in the dam’s history, was merely 5 percent of the design discharge. Known structural problems with the dam’s primary spillway were ignored for over a decade. The projected maintenance costs were in the millions of dollars, and maintenance was deferred. The final repair bill was over $1 billion and was passed on to the federal government.

Who needs to act, and what needs to be done to address this massive problem?

There is the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, with state dam safety offices as members. The Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Bureau of Reclamation each have a national dam safety program. Despite the ongoing efforts of these groups, and existing legislation and policies for the inspection and re-certification of dams, we lack a cohesive strategy to fix the problem.

The Edenville Dam lost its federal hydropower certification in 2018, yet it was still operating when it broke. Boyce Hydro, its owner alleges that the failure is due to the State of Michigan requiring it to keep water levels high for environmental reasons. This is disputed.

The majority of the 90,000-plus dams in the United States are older their design life, which could be as little as 50 or 60 years. Their condition is a concern, and this is the silent hazard that needs to be addressed. The National Inventory of Dams, a database run by the Army Corps of Engineers, lists approximately 25,000 dams that are listed as high or significant hazard. Some 10,000 are high-hazard dams that could kill people. This is a national concern — every state has such dams.

Flooding from dam failure can be much more catastrophic than what may be expected from an extreme rainfall event, if the flooding causes further damage downstream. The Michigan dam failures are one example of this cascading dam failure. The failure of the unsatisfactory Edenville dam led to the failure of the downstream Sanford dam that was rated fair.

The dam failures in Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, in 1972, provide another example. Three dams failed in sequence, mobilizing a large amount of coal mining waste, rendering 4,000 people downstream homeless and killing 125.

Our recent report on the risk from dam failures in the United States highlights that much critical infrastructure — other dams, electricity generating plants, highways, bridges, water treatment and wastewater treatment plants — lies below dams and would be incapacitated in the event of dam failure leading to significant and potentially chronic economic impacts.

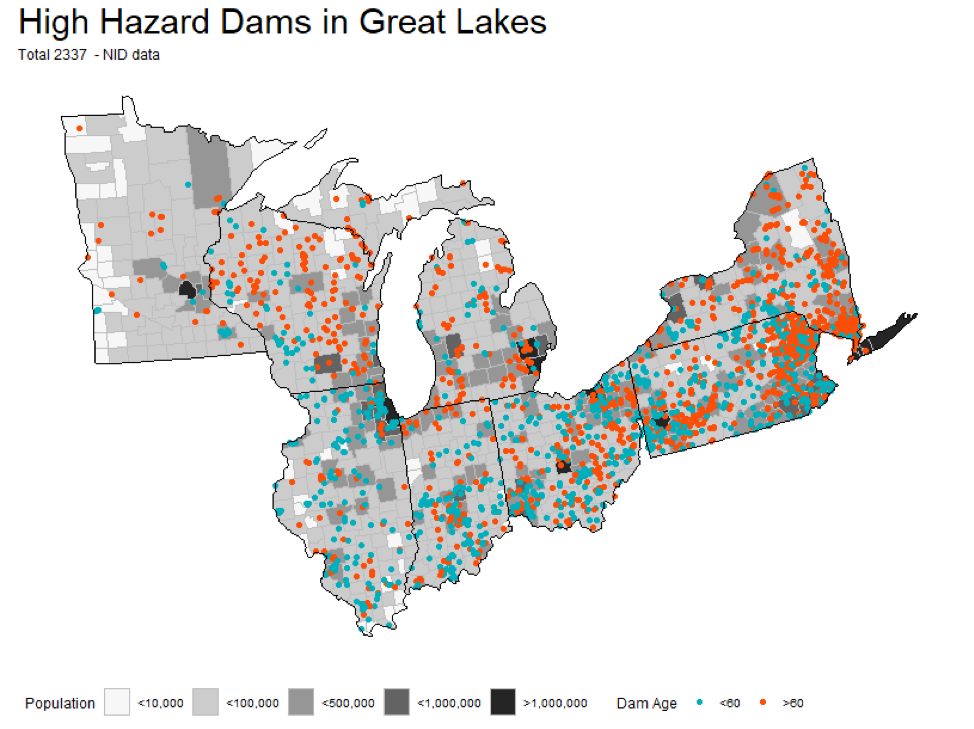

High hazard dams in the Great Lakes region, by age and with county populations shown. Source: Columbia Water Center

There continues to be no comprehensive evaluation of these risks or a prioritized list of dams for remedial action. Does it make sense to keep doing Presidential disaster declarations each time a dam fails, or is it better to prioritize which ones to fix or remove before disaster strikes? Our report provides an approach that could be used to do this “rapidly” but has not yet been applied nationally due to financial and time constraints.

Michigan, the location of the most recent dam failure, is in the Great Lakes region. There is a profusion of high-hazard dams older than 60 years in counties with high population. These areas are also likely to have valuable assets such as thermoelectric power plants, waste facilities, and drinking-water intakes located along rivers.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan characterized the Midland dam failure as a 500-year event, or something that would have a one-in-500 chance of occurring in any given year. If we consider dams older than 60 years in counties with a population larger than 500,000, we have 317 high hazard dams, and the chance of one or more dams experiencing a 500 or 1000 year event in a year would be 47 percent and 27 percent respectively — pretty high, actually. While not all would lead to a failure it is something to think about.

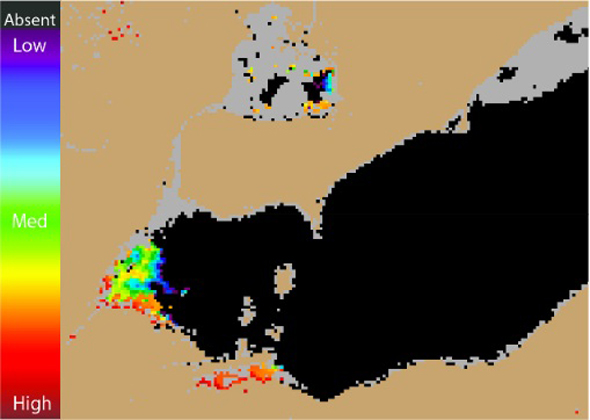

Climate shifts are yet another factor to consider. Extreme rainfall events are happening much more frequently than in the last 100 years. Water levels in the Great Lakes are at record highs. In this wet cycle, it is possible that more dams will fail. The question to ask is what the state governments in the region are doing to deal with potential floods and dam breaks.

The New York Times and the Associated Press have published information on the inspection frequency and condition of dams using Freedom of Information Act processes for at least a decade. The National Inventory of Dams provides information on some basic statistics of the dams, but selected information is no longer made available in the interest of “national security”. A hazard and prioritization analysis, such as the one we prototyped, could be done quite rapidly given data and resources, to at least screen and identify the subset of dams that needs urgent attention and investment by the federal government to avoid a future disaster declaration and the associated cash outlays.

Yet, we do not see any of the agencies responsible pursuing such a strategy and/or informing the public of the collective risk the nation faces. In the age of big data, it is imperative that this be done as the first step in a process that eventually fixes the dams or removes them, with stakeholder input.

Upmanu Lall is the director of the Columbia Water Center. Paulina Concha Larrauri is a researcher at the Columbia Water Center.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!