Speaking of Water – Featuring Australian Author And Science Communicator, Julian Cribb

Surf’s beach, south of Bateman’s Bay, NSW. Image courtesy of Isobel and Nicholas Davis © Dec 31, 2019.

Eileen: I’m Eileen Wray-McCann for Circle of Blue. This is Speaking of Water, a look into vital water topics that often flow beneath the surface of the daily headlines. The world economy, civilization, and maybe our survival as a species are on the line.

Julian: Thank you, Eileen.

Eileen: The Australian bushfires have compelled our attention and demanded action, but another crisis, perhaps less dramatic, has long been unfolding in your country. The big dry has been a frequent challenge. And in fact, in your latest book, Food or War, you describe freshwater scarcity as an emerging and critical systemic risk worldwide, even a potential cause for wars. And you say that of all the emerging resource scarcities it is the swiftest and deadliest. Could you talk about that?

Julian: Yes. Well in a sense, the bushfire crisis is a direct result of the scarcity of water in the landscape, because when the Australian landscape is wet and well-watered, it doesn’t burn. But we have had this horrendous drought, very sharp, severe drought and it comes not long after we had a millennium drought, which lasted 10 years. The bushfire crisis is a direct result of the scarcity of water in the landscape, because when the Australian landscape is wet and well-watered, it doesn’t burn.

Eileen: And when you describe it as swift and deadly, of all the resource scarcities, could you compare that a little bit and give us a perspective on that?

Julian: Yes. Well, climate change is building up. It’s not as bad as it’s going to get and it’s going to get far worse by the mid century. But water scarcity is occurring all the way around the world, so it’s not just in Australia, it’s not just, say, in the southwest of the United States. There is major water scarcity occurring on the Indian subcontinent. There’s major water scarcity occurring in Northern China as the Chinese aquifers there run dry. The middle East is already out of water and North Africa is very, very water scarce at the moment. There’s water scarcity in South America and Central America in Southern Africa and a Sub-Saharan Africa. It’s absolutely everywhere. We’re seeing crisis after crisis of water rising worldwide. Now, these are not well covered by the world media. You only get to hear about some of them, but basically the huge world water crisis is building up and it’s going to hit us this decade.

Eileen: Will you also talk about what we call here the choke point between, for example the farming industry and the need for water there, and the challenges that as population grows and industrialization grows, that there is a competition for water use. There’s no more water being created so there is that whole scenario.

Julian: Yes, like many people, we have reached the end of our water supplies, basically. The reasonable end. I mean we’ve been extracting water out of the landscape, out of the rivers, out of the groundwater like there is no tomorrow, and we’ve been doing that for a hundred years, as indeed has been the case with the central aquifers in the United States, as indeed has been the case in the Middle East and anywhere that is basically water-scarce. So we’ve been taking that water. We never bothered to see how much water was there before we started extracting. We just took it for granted that there was going to be enough water for whatever we wanted to do, whether it was for agriculture, whether it was for manufacturing, whether it was for cities to drink, whatever. We just assumed there was going to be plenty of water because the rain would bring more.

Julian: But that’s not the case. If you clear the landscape, you eliminate the small water cycle, which removes the water that’s cycling in the local area. So that reduces your rainfall. And of course climate change is producing this very jerky pattern of rain pool distribution in the dry latitudes. Climate change is producing this very jerky pattern of rain pool distribution in the dry latitudes.

Eileen: You mentioned that in Australia water has become a commodity, and you called it the plaything of the rich and powerful. Could you describe what has happened since water rights have essentially become negotiable?

Julian: Once we started to get into considerable water scarcity, particularly in the Murray-Darling Basin, the economists came up with the idea, as economists always do, that when something is scarce, you create a market for it, and the price that is then put on that water manages the demand. Unfortunately that idea doesn’t work, because it’s not confined to Australia. So farmers were able to sell their water entitlements, but those water entitlements could be purchased by gamblers in Wall Street or Chinese corporations. People who just want to sit on the water and wait for the value to go up so they can sell it to somebody else. In other words, the water is not doing anything useful at all anyway, but it’s being held back from the rivers in large dams, private dams and things like that. So it’s another form of the financial community destroying the basic resources which humans require to survive.

Eileen: Does the environment have any entitlement to water? Does the river itself have any entitlement to its water?

Julian: Yes. At that time, the Murray-Darling Basin Commission was setting aside 30% of the flow or thereabouts to be given to the environment. In other words, to keep the red gum forests and things like that, watered periodically. It’s not nearly enough, but they were at least trying to keep the landscape alive, and the Australian landscape is driven by water. So that was the purpose, but unfortunately now water supplies are so tight in this climate-driven drought that the farmers don’t have enough, so they want all that environmental water given back to them. They’re angry, they want the whole agreement torn up. I mean basically everyone’s at one another’s throats over this and the situation is just getting worse and worse.

Eileen: What role is the government playing in this?

Julian: Very little. They don’t actually care. In fact, the government has been responsible for some disgraceful selling of public water assets. Individual politicians have been making tens of millions of dollars flogging off our water. It’s a total scandal this large scale corruption taking place in the political machine.

Eileen: What about people? Are there any initiatives for conserving water or dealing with this problem if the government is turning a blind eye to this?

Julian: They can’t turn a blind eye because there are towns in Australia now which depend on water trucks carting drinking water into the town because all of their rivers and dams are dry. So there are whole country towns now that they need to import water to slake their thirst. So governments can’t ignore that, but they are doing as little as possible and they are feathering the nests of the very rich. So water is still being sold to very rich owners, and these people are not interested in Australia or in a secure food supply or in people in country towns having enough to drink and wash themselves. It’s just an absolute scandal. There are towns in Australia now which depend on water trucks carting drinking water into the town because all of their rivers and dams are dry.

Eileen: There’s also something about initiatives in the cities. Could you talk about what people are doing in urban areas?

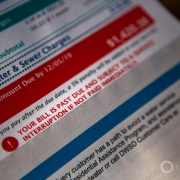

Julian: In a drought in Australia, when the dams run low, the local authorities enforce water restrictions, and those water restrictions normally are things like you can’t water your lawn, or you can’t wash your car in the street, et cetera, et cetera. And you get charged a lot more money for your household water if you exceed a certain limit. So they ration water that way and that has been quite a successful program over many years. Australians do respond to that when they know there’s a scarcity, and they know the dams are running very, very low. Then they do buckle down and save water, but most of the time they’re pretty relaxed about it I have to say, and meanwhile in the background and over the large landscape, there is just gross mismanagement and corruption of water administration.

Eileen: Could you talk a little bit about ideas that people have to reuse water and to cope with the limited supplies that are available now?

Julian: We’ve had a few attempts to reuse water in Australia, but unfortunately it’s not been terribly successful because people frankly don’t like the idea of drinking their own piss, even though of course they’re drinking water that’s been through animals for thousands of millions of years. So there’s this strange debate that goes on. So at the moment, our big cities are pouring their waste water into the ocean where we can never use it again. So all the waste water that goes down the sewage pipelines and the drains and the storm water outlets and things like that, ends up in the Pacific or the Indian Ocean or something like that. It’s a complete waste. It could very easily be retrieved and reused. And of course, water scientists have been saying this for decades. We have the filtration systems to cleanse it to drinking water standards. There’s no technical problem about recycling your water. It’s just that governments, which are driven by stupid voters, don’t want to do it.

Julian: I think it’s got to come because frankly these big cities will run out of water otherwise, so they’re going to have to recycle their water. That said, there’s a lot of good work going on. One of the best developments in Australia has been the steady growth in aquifer recharge, where we actually harvest storm water and things like that from across the landscape or across the city, and we inject it into the underground aquifer.

Julian: Now this makes a lot of sense because unlike a surface dam, there’s no evaporation. In Australia, we get water evaporation rates of one to two meters per year. So you need an awful lot of rain to overcome just the evaporation. So if you can inject your water into an aquifer, you’re creating an underground dam and that water can then be saved. And there are a number of areas, like the city of Adelaide and the Bowen Basin in Queensland, where water is injected into the aquifer and then brought up again water crops or to water city parks and things like that.

Eileen: Sounds like some very good ideas.

Julian: There is a lot of good thinking, clever thinking about water use, and Australian farmers, I may say, are very, very water efficient. They’re probably the most water efficient rice farmers in the world in terms of tons of rice for a mega liter of water. There’s quite a lot of technology used and good thinking used, but the overall management of the system is corrupted by politics.

Eileen: You talked earlier too about how foreign companies are buying water rights. Could you explain a little bit about how that works and what that means?

Julian: We all know that China does not have enough water and soil to feed itself in the long run. We all know that China does not have enough water and soil to feed itself in the long run.

Julian: So there’s a worldwide movement by these water poor countries of the world. There’s the people in the Middle East, and China, and East Asia. They’re buying up the water rich assets in South America, in Australasia and so forth. Water has become a global commodity like gold or iron ore or something. And I think that’s a very dangerous thing, because it’s become thus a gambler’s play thing. It’s no longer something that creates life and sustenance for the human species. It’s become just another roulette chip or another chip on the gambler’s table.

Eileen: So if you have areas that are essentially relying on tankers of trucked-in water that comes from presumably other water sources that are not under stress now, what happens when Australia has sold water rights outside the country, and its own citizens don’t have enough water?

Julian: Well, the current governments of Australia are the ones who’ve sold the water. Now they are under heavy criticism from these rural communities that don’t have enough water, from the farming industries that haven’t got enough water. But they didn’t know what they were doing when they sold the water off. They thought they were just making money for themselves and maybe for general revenue, but to be honest with you, they had no idea what they were doing and they’ve just unleashed the whirlwind. So it’s an unsolved problem at the moment.

Eileen: So there’s no guarantee that there’s water behind that money. It may not be there?

Julian: Well, in some cases that is true, actually. The water doesn’t in fact exist. There was $80 million worth of water that was sold that simply didn’t exist. So there was a lot of shonky things that have gone on in the background here. It’s a pretty good example of how not to run a water economy, but then I have to say the same sorts of corruption are endemic in a great many other countries around the world. I read fairly horrendous things about the early days of water extraction in California for example, all the people fighting over water resources there.

Julian: So as Peter Gleick at the Pacific Institute has pointed out, the level of conflict over water resources is rising year by year and even month by month around the world. The intensity of the conflicts, the bitterness of them, the danger of them is growing and growing. And if you look at, for example, the Indian subcontinent, there you have India and Pakistan at daggers drawn over the waters of the Indus. There is not enough Indus to feed both India and Pakistan. Not enough Indus water any longer because the glaciers in the Hindu Kush and the Himalaya that feed into the Indus River are melting.

Julian: And so the water tower that feeds those giant rivers on the Indian Plains is dwindling. It’s like a dam that’s emptying. There’s a very real risk that India and Pakistan could come to blows over water, which is of course over food, because they won’t have enough to grow food for their people. And of course they are both equipped with nuclear weapons. They have 250 nuclear warheads between them and they would only need to let off about 50 or 100 of those to actually destroy the global food harvest in a nuclear winter. So if they did have a nuclear confrontation over water or indeed any cause, then it would affect every single country on earth.

Eileen: Wow. I’m sure you’ve been following the story of our California wildfires, in particular the town of Paradise that is turned into a hell actually, burned to the ground. Not only did everything burn the action of the wildfire has destroyed the whole infrastructure for water and polluted, essentially, the aquifer in that area. Any concerns about what the wildfires are going to mean for water in Australia? hen you clear a landscape with an enormous fire, what happens is the soil and the ash both wash down into the rivers, and the rivers become totally polluted, the oxygen is stripped away, and the fish die. The whole ecology of the river is just basically destroyed for a period of time.

Julian: Oh yes. Really serious concerns. I’m familiar with the Paradise area. I used to go steelhead fishing up that way once upon a time. But yes, the same sorts of things happen. When you clear a landscape with an enormous fire, what happens is the soil and the ash both wash down into the rivers, and the rivers become totally polluted, the oxygen is stripped away, and the fish die. The whole ecology of the river is just basically destroyed for a period of time.

Julian: Now here in Australia, about three months ago, we had massive fish kills in the Darling River and inland rivers just because the rivers dried out completely. But now we are seeing in the other rivers that have still got water in them, massive fish kills again. The cause of all this ash and sediment that is washing into the rivers, following the bushfires. People in the big cities, a water scientists are warning, that’s the drinking water supply could become toxic as a result of all of the chemicals that wash into the dams that supply the drinking water to the cities. So there’s a real concern here about the health and safety of drinking water, but also the entire ecology of the aquatic system. [pullquoteIin Australia, about three months ago, we had massive fish kills in the Darling River and inland rivers just because the rivers dried out completely.[/pullquote]

Eileen: What are people saying about this?

Julian: We’ve got koalas being incinerated in the forests. We’ve got endangered species being extinguished in these giant fires. There is so much tragedy around, human lives are being lost almost every single day. You probably heard about the crash of the tanker aircraft that was trying to put out a bushfire. These kinds of tragedies… people are just overwhelmed to be honest with you.

Julian: What we are doing is we are seeing the start of the Anthropocene, that era where human action changes the entire planet. And this is the world that everybody is hitting into, because there are wildfires in Canada, Siberia, Indonesia, everywhere. This problem of soil and ash going into the water supply is multiplying around the world. In the Amazon, you name it. This is a universal problem and it’s all being driven by this gradual, gradual rise in the temperature of the earth’s surface.

Eileen: People think of water as separate from climate. Would you speak to that?

Julian: Water is of course a part of climate, and the heavy rainstorms and the floods that we’re seeing in Jakarta and Southeast Asia now, they are the product of global warming, because what is happening is that there is more increased evaporation, so you get heavier dumps of rain in the tropics. In the dry bands around the world, on the two Tropic lines, that’s where you’re getting the rivers are emptying, and rivers are emptying everywhere. Lakes are disappearing all over the world. Hubei Province in China used to be known as the province of a thousand lakes. They’ve got less than a hundred lakes left. Just everywhere you look, lakes and rivers are disappearing in those arid bands around the planet, and in the tropics they’re getting inundated with these massive dumps of rain caused by the increased cycling of evaporation and so on. So really we have destabilized the entire aquatic system for the planet, and that’s starting to have very big effects, and it’s going to affect human civilization in a profound way.

Eileen: So what do we do about this? What do people do about this?

Julian: Our biggest impact on the planet as human beings is our jawbone. It is the most deadly implement. It dislodges 75 billion tons of top soil every year. Every single meal that you eat, every single meal that each of us eats, consumes 10 kilograms of topsoil, 800 liters of water, a liter and a half of diesel fuel, a third of a gram of pesticide, three and a half kilos of carbon dioxide. That’s what’s in every single meal, every single day, for every single person. So 24 billion meals every day, the resources of the earth are stretched to the absolute limit. And water is the most critical resource because we cannot do without it. Our biggest impact on the planet as human beings is our jawbone. It is the most deadly implement. It dislodges 75 billion tons of top soil every year. Every single meal that you eat, every single meal that each of us eats, consumes 10 kilograms of topsoil, 800 liters of water, a liter and a half of diesel fuel, a third of a gram of pesticide, three and a half kilos of carbon dioxide.

Julian: Now, what can we do about that? Well, the answer is we have to grow food using far less water. At the moment, three quarters of the world’s water is used to grow food on irrigation of crops and pastures. We have to get away from that system. We have to grow food using the recycled water from our cities, in our cities, and that’s becoming possible with hydroponics and aquaponics and techniques like that. So if we recycle our water and we do it through greenhouses where there is no evaporative loss, then you can have a closed loop water system where you lose no water in the process of producing food.

Julian: So we can have a renewable food supply provided that food supply does not require a lot of topsoil and does not require very much water. Urban food production can produce the same amount of food with one tenth of the amount of water we currently use for the agricultural system. If you produce far more food in the deep oceans, in aquaculture, aquaculture efficient and water plants, then again you don’t need any water because the ocean supplies all the water that you need.

Julian: So there are ways to produce a viable human food supply without taxing water to its absolute limits. But at the moment we’re being a little bit slow in getting onto those new techniques. I’m expecting there to be a revolution in renewable food just as there has been, or is already, a revolution in renewable energy.

Eileen: You also mentioned fossil fuels was another major contributor that individuals can make choices about.

Julian: The world has to get off fossil fuels, full stop. Within 20 or 30 years we must be using zero fossil fuels. That’s what the science is telling us. Otherwise we are going to face these vastly disruptive food systems, and that is going to lead to mass migration of hundreds of millions of people. And that is going to lead to war, large scale war. So if we want to avoid that particular pathway, we have to ditch fossil fuels. But there’s lots of ways that we can supply energy that don’t involve fossil fuels. We already know we can produce electricity from sunlight, from wind, from tide, from ocean currents, from all sorts of things. We can produce all the oil we ever need for transport out of fresh algae. That’s liquid solar energy, you just use algae to produce oil, which you then put into your car and drive away, basically, if it’s a diesel. The world has to get off fossil fuels, full stop. Within 20 or 30 years we must be using zero fossil fuels.

Julian: So there are lots and lots of solutions. We just have to get onto those solutions a lot faster. We need to make the transition from a fossil economy to a renewable economy much more quickly. That only happens when consumers start to realize that they are the ones responsible for the transition. Now, many consumers are realizing that they can put solar arrays on their roof and they can generate the electricity they need for their home from sunlight.

Julian: Just as they’re realizing that, they’ve got to look for other ways of eliminating fossil fuels from their lives. Whether it’s fossil fuels in the form of fuel for their vehicle or whether it’s fossil fuels in the form of plastics, in the form of their T-shirt, their textiles that they wear, the pharmaceuticals that they take when they’re ill, we have to replace all of those fossil sources with clean, fresh energy that does not pollute the planet with carbon dioxide. This is quite doable, but it requires very high levels of awareness in the community so that when you go into a shop, you buy the product that is sustainable and you send the profits to the sustainable, the rewards go to the sustainable company, not to the unsustainable company that is wrecking your grandchildren’s future.

Eileen: These challenges seem huge. What’s the bigger picture to keep in mind?

Julian: Well, I’ve written four books on the existential threat facing the human race to get people to understand what we’re actually looking at, and I’ve gone to the best scientific institutions and scientists in the world to get that information, and explain it to people in plain language. So my book Surviving the 21st Century and Food or War and things like that, they’re all looking at the threats that our kids and grandkids are now facing.

Julian: Basically, those threats are all capable of being solved. All capable of being solved, but they can’t be solved one by one. They must be solved by integrated action that makes none of them worse. For example, you can’t solve the world problem of food just by throwing more fossil fuels at the food problem, because if you do that, you’ll wreck the climate that we need to grow food in. So the solutions have to be cross cutting and they have to make none of these existential threats or catastrophic risks worse.

Julian: I detail the solutions to all of these problems in my book, Surviving the 21st Century. Not only the things that governments have got to do, but also what every single one of us can do in our own lives. At the end of the day, it is our behavior as consumers, the things that we buy, that determines the behavior of corporations, and corporations in turn determine the behavior of governments.

Julian: So if we buy food or products that are unsustainable, we will mine and destroy the planet. If we buy products that are sustainable, we will reward the corporations that practice sustainability and the farmers who practice sustainability and regeneration. That’s the key to it. Each one of us needs to be responsible. We are no longer a clutter of nations on a big planet. We are now one people on a single diminishing planet and we have to stand together. We have to be one another’s friends and allies in solving these problems. We cannot afford to be one another’s enemies. If we do that, we will just take down the world. if we buy food or products that are unsustainable, we will mine and destroy the planet. If we buy products that are sustainable, we will reward the corporations that practice sustainability and the farmers who practice sustainability and regeneration.

Julian: So we have to solve this problem by a worldwide effort of human understanding. Now, I believe that humans are quite capable of understanding this. None of the solutions are impossible to implement. None of them require new technology that doesn’t exist, to be invented. They are all capable of being solved with the tools we have today. What we lack is the willpower to do it, the understanding of the threat, and the institutions that are prepared to do it. At the moment, the gravest danger is that our major institutions, ie our federal governments, are actually opposing the solving of these problems.

Eileen: You mentioned too that this is an exciting time in our history as a species because of how we were able to communicate. What’s the prognosis for that?

Julian: A million years ago we existed in very small family groups and they gradually grew into tribes and things like that. At that point we lost contact with one another, but since the advent of the internet and social media, for the first time it has become possible for humans to have a conversation around the entire planet. More than half of humanity is already on the internet. By 2030 the whole of humanity is going to be on the internet. So it is going to be possible for us to share the same information about the problems we face and the same information about the solutions to those problems.

Julian: Now the internet is full of wonderful stuff. You can look at any science that’s been published by Harvard or the University of California or Oxford or Cambridge. So you can have access to the very best in human knowledge, and you can have it at the speed of light, more or less. That’s the wonderful thing in the internet.

Julian: The flip side is it’s full of rubbish. It’s full of malignancy, and untruths, and people making things up, and just amusing themselves really, not knowing the damage they’re doing. Now the answer to that, there’s only one answer. When you go into the market as a consumer, you have to be able to tell the difference between a good apple and a bad apple. You have to discern what is good from what is bad. When you are a consumer of the internet, you also have to be able to tell what is good from what is bad, what is deceiving and misleading from what is truthful and well attested, well validated, peer reviewed, et cetera, et cetera.

Julian: So it’s a case of people learning to use the internet properly and understanding that when they misunderstand what they’re seeing on the internet, they are actually damaging their own chances of survival and they’re damaging their own grandkids. That message has to spread pretty quickly. But fortunately, social media and the internet operate at the speed of light and for the first time in the whole of human history, people are now exchanging thoughts and ideas and solutions to these mega risks at light speed, and they’re exchanging them across countries, across linguistic barriers, across social barriers. For the first time the human race is starting to speak together.

Julian: This is a very important time in human evolution. We are learning to think as a species. Now, all right, it’s only in the embryo stages, but we can only solve the 10 great catastrophic risks to our future by acting together, by understanding those risks first and then understanding what the solutions to them are.

Julian: But if we do that, and if we share that knowledge, like the farmers who are sharing the knowledge of regenerative agriculture on social media right now at this moment, there will be hundreds if not thousands of farmers sharing their experiences with regenerative farming. So this is a wonderful example of the spread of the new sustainable knowledges that’s going on right now.

Julian: We can fix these problems hopefully before too many of us die. No species in the whole of earth history has ever had a population boom like ours and not had a population crash. So the only question really is, is our crash going to be a managed one or is it just going to happen as a result of our resources running out, or a big nuclear war, or something? So that is the choice before us, and we can choose to go towards the path of wisdom and sustainability and renewal in our environment, or we can choose the path of conflict, misunderstanding and war. We can fix these problems hopefully before too many of us die. No species in the whole of earth history has ever had a population boom like ours and not had a population crash.

Eileen: We have the ability to see our world, whether it’s our planet or our ecosystem, in such minute detail in order to actually see what’s going on and communicate that around the world. I think that in some ways it gives us the advantage of the sense that for example, our indigenous cultures have always had about their environmental world.

Julian: Every indigenous culture, it was a life or death affair if you did not understand your environment. If you failed to understand it, you would probably die of starvation. So they always had to know what was going on and they had very good systems for storing that knowledge and passing it on to future generations. We’ve been a bit too clever for ourselves. We keep on inventing a lot of technical things that look like solutions for a time. I mean coal looked like a wonderful solution in the 19th century, but it’s turned out to be an absolute killer. Coal and oil between them kill 9 million people a year. So these things that looked like great ideas 100 or 200 years ago, we’re discovering that they’ve got downsides, and we have to either remedy those downsides or we have to change the way we actually do whatever it is we’re doing. Whether it’s transport or whether it’s producing food or whether it’s using water, whatever.

Julian: That’s progress basically. It’s a very exciting time in that sense. But it is a race against time. If we do not succeed in solving these problems, really by the mid century, the human species is going to be an awful lot of trouble. We’re not going to be able to feed 10 billion people on a hot world that is deficient in water and soil and all the other basics we need for life. So there is a crunch point coming and we’re going to see more and more of these warning signs like the Australian Bush fires, or the Californian fires, springing up around us and telling us you’ve gone too far. You are overusing your planet, you’ve got to pull back. You’ve got to do it a different way. So we’re hearing the warnings now. Intelligent people are sharing those warnings. Greta Thunberg, for example, is an example of the inspired youth who is leading us to a safer place.

Julian: Women worldwide are at the forefront of this movement. It is men who make the wars, it is men who mine the earth, it is men who cut down the forests or empty the oceans. It’s not women. Women would prefer to do things in a more conservative way, and they think about their children and their grandchildren and what they will need to survive. And for that reason, women have taken a universal decision to reduce their fertility worldwide. They have halved their fertility in the last 40 years. They did not ask men for permission to do it. So women are the natural leaders of our planet when it comes to a sustainable human future. We have to listen to women. We have to put them into positions of influence and power because I’m afraid if it’s left to men, men will just throw more technology, and more bombs, and more wars, and things like that at the problem. That’s their natural reaction. That’s the natural instinct of males over the eons. We need a far more peaceful, rational, and balanced solution to the problems that humanity is facing today. Women worldwide are at the forefront of this movement.

Eileen: You have a granddaughter, yes?

Julian: I’ve got two granddaughters and a grandson. Yeah.

Eileen: Do you talk to them about what the world is facing? What do you say to them?

Julian: My grandchildren are aged between naught and three years old, so I’m not talking to them about these issues just yet, but their parents are aware of all these issues because I’ve been writing about them for decades. They’re living the dream in some ways, they’re changing their entire lifestyle to get rid of fossil fuels, get rid of chemicals out of their homes, to live a sustainable, low energy life and so forth. I’m very, very proud of the efforts that they’re making as human individuals to do this. Candidly, the future of everybody’s grandchild is at stake. If we do not fix these problem, we are sacrificing those grandchildren, and that’s what motivates me. That’s why I get up and get out of bed in the morning. I’m trying to save my grandkids. I’m trying to save a green, sustainable, water-rich planet for my grandchildren.

Eileen: Thank you, Julian. I look forward to talking to you again soon on many topics.

Julian: Thank you very much, Eileen.

Eileen: That was Julian Cribb, Australian science communicator, whose most recent books are Food or War and Surviving the 21st Century Humanities Ten Great Challenges and How We Can Overcome Them. I’m Eileen Wray-McCann for Speaking of Water, from Circle of Blue for Water Speaks. Thanks so much for listening in.

Eileen Wray-McCann is a writer, director and narrator who co-founded Circle of Blue. During her 13 years at Interlochen Public Radio, a National Public Radio affiliate in Northern Michigan, Eileen produced and hosted regional and national programming. She’s won Telly Awards for her scriptwriting and documentary work, and her work with Circle of Blue follows many years of independent multimedia journalistic projects and a life-long love of the Great Lakes. She holds a BA and MA radio and television from the University of Detroit. Eileen is currently moonlighting as an audio archivist and enjoys traveling through time via sound.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!