U.S. Water Data, Refreshed Daily

New U.S. Geological Survey tool displays where water is – and isn’t – in the Lower 48 states.

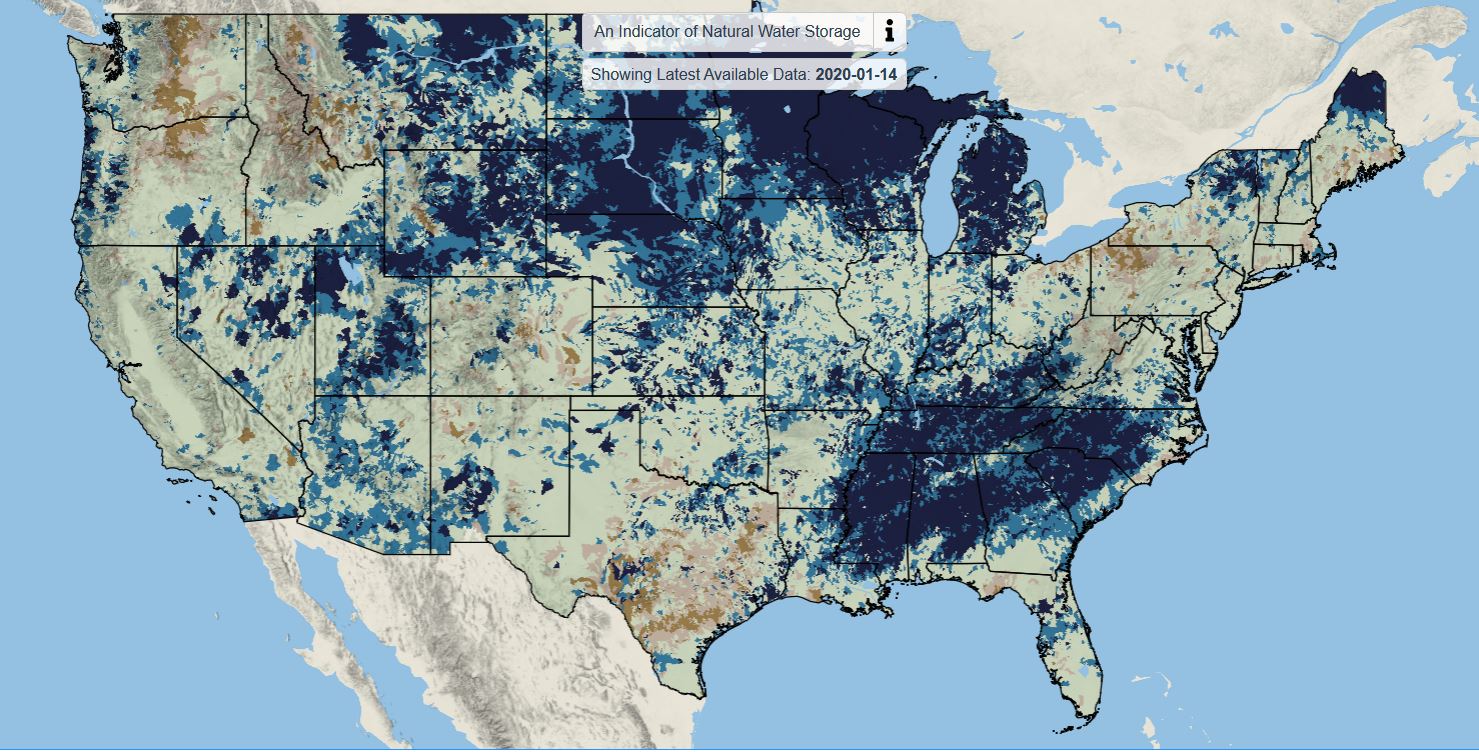

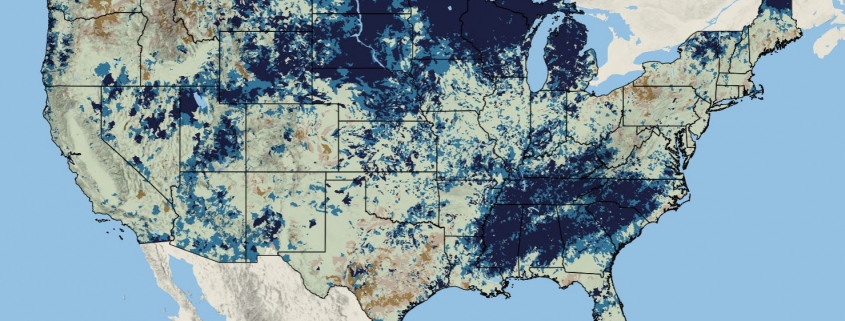

Screenshot of the U.S. Geological Survey’s water availability tool. Dark blue indicates areas where the amount of water stored in soil, shallow groundwater, and snowpack is very high compared to the long-term average. Dark brown areas have very low storage.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Where is the water?

A new mapping tool from the federal government’s top Earth sciences agency aims, with greater frequency and detail, to answer that basic question about the nation’s water resources.

Updated daily, the map displays a nearly complete picture of water storage in the Lower 48 states. It shows water currently held in snowpack, soils, and shallow groundwater compared to the long-term average. It also incorporates moisture trapped in the tree canopy and wetlands, but it does not include rivers, reservoirs, and deep groundwater.

The data that informs the tool will be helpful in a range of applications, analysts say. From forecasting droughts and floods to notifying farmers when to fertilize crops so that nutrients do not pollute rivers.

A glance at the map today shows very high saturation in the upper Missouri and Mississippi river basins. Parts of the region just experienced the wettest 12-month period on record, a stretch punctuated last year by historic flooding that inundated towns and prevented farmers from planting corn and soybeans on nearly 16 million acres. If wet conditions remain in place, the region could be on alert for another round of flooding this spring.

The tool is the first of three mapping products that the U.S. Geological Survey is rolling out in the next two years, said Mindi Dalton, the coordinator for the USGS Water Availability and Use Science Program. The tools are intended to fulfill the agency’s mission to improve understanding of the nation’s water.

Dalton told Circle of Blue she is pleased with how the water availability tool turned out. Staff are now working to deploy similar tools for daily water quality and use.

Water data analysts are also excited by the prospect of more timely information.

“This is a novel and hugely useful development,” Peter Colohan told Circle of Blue. Colohan is the executive director of the Internet of Water, a data project based at Duke University.

“In our world, we’re thrilled with every new data set because there are so many questions and unanswered questions,” Colohan said.

Integrated Data

The USGS tool answers the question of quantity. It ranks natural water storage from very high (exceeding 90 percent of past observations) to very low (in the bottom 10 percent of observations).

But besides storage, there are other considerations.

When she took her current coordinator job, in 2018, Dalton sought to integrate water assessments for quantity, quality, and use that had been operating somewhat independently. Each factor influences the other: heavily polluted water has more limited value.

“There are any number of uses for water,” Dalton explained. “Water used in mining is of a different quality than water used for public supply. If you’re just running a model for quantity and not taking into consideration the quality and use, then you can’t really say how much water is available.”

It’s this integration of data that excites Colohan, who previously worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. When researchers can combine and manipulate multiple data sets, it opens the door to new products and services.

Those services translate raw data into information, said Amir AghaKouchak, a researcher at the University of California, Irvine, who studies water resources modeling.

And information — like what is presented on the map — is what is most useful for farmers, developers, city managers, water utilities, and others. With the mapping tools, “USGS is moving more toward this direction,” he told Circle of Blue

Potential applications for a daily water storage assessment are numerous, Colohan said. Nutrients from farm fields are a substantial water pollution challenge. Fertilizers applied to saturated fields can be more easily washed away by rain. The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture designed an online tool that tells farmers when to spread manure to minimize runoff. Combining water storage data with weather forecasts can indicate whether nutrients are likely to remain on the field.

Those sorts of applications are possible only when the data is open. The numbers underlying the USGS mapping tool are publicly available, but not easily accessible, Dalton said.

Future updates of the map will include a search function, Dalton said. Users will be able to click on an area of interest and download the data for that watershed.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!