California, Texas, and the Southwestern U.S. Face a Critical Year for Water Supplies: 2014 Preview, Part I

After a dry 2013, reservoirs are near record lows for the start of a calendar year, setting the table for widespread water restrictions, reduced agricultural and energy production, and political bickering in 2014.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Like a human pulse, reservoirs are the most obvious indicator of a water-supply system’s health. At the beginning of 2014, three major U.S. regions are suffering, and the consequences touch all limbs of the body politic.

A topic attracting fervent debate in a normal year, water will crown the list of public policy concerns in the Western United States in 2014. Farmers will worry about having enough moisture to plant a crop. Farmworkers will be laid off. Hydropower generation will drop and force utilities to buy electricity on the market, a more expensive option. The recreation economy — which depends on reservoirs and rivers for boating, swimming, and rafting — will sag. In the summer, wildfires may rage. And arguments about how best to use a dwindling resource will reverberate from Austin to Sacramento.

Reservoirs in the nation’s two most populous states and in a watershed that supplies 40 million people with drinking water face unprecedented circumstances. Water reserves in parts of California, Texas, and the Colorado River Basin are at record lows for the start of a calendar year.

- In California a third consecutive dry year has prompted Governor Jerry Brown (D) to declare a drought emergency. Snow is scarce, at just 15 percent of normal as of February 5. Severe water cuts for farmers in the Central Valley, an agricultural kingpin, are expected. Fires are already burning in the southern hills – this during January, typically the rainy season. At least 17 communities are at risk of water shortages in the next 60 to 100 days. At the same time, the state is mulling two plans that would pump tens of billions of dollars into water projects: $US 25 billion for a pair of tunnels through the politically fraught and environmentally fragile Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and a multibillion-dollar water infrastructure bond for the November ballot that is still being negotiated.

- In Texas, voters approved their own water bond last November – a $US 2 billion outlay. Now comes the haggling over which projects will see the money. State legislation set aside 20 percent of the funds for conservation, but supply-side solutions are sure to dominate discussions, especially with reservoirs and aquifers so low. Parts of central Texas, including the cities of Austin and San Antonio, face water restrictions.

- Along the Colorado River, the driest 14-year period in the historical record — which dates to 1908 — has set the stage for a first-ever declaration of water shortage for users in Arizona and Nevada. A shortage will not happen in 2014, but the amount of precipitation this year will determine whether water restrictions come sooner or later. Las Vegas, one of the Southwest cities that is most vulnerable to a shortage, will scramble to finish an emergency water connection in Lake Mead, its principal supply source.

Worse, long-term weather forecasts do not promise a reversal of fortune. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reckons that dry conditions will hang over these regions through the spring. Read below for a detailed analysis of each region’s problems and potential solutions.

California: Little Water in the Hills

California broke a record in 2013. A wall of high pressure – dubbed the “ridiculously resilient ridge” by weather watchers – blocked moisture from the Gulf of Alaska from reaching the Golden State, which experienced its driest year since recordkeeping began in 1895. Analysis of tree-ring data indicates that 2013 was one of the driest years since Magellan sailed the Pacific. The current drought, now in its third year, coincides with a potential turning point in a longstanding debate about how to overhaul the state’s far-reaching water supply network.

Two canal systems – one operated by the state, the other operated by the federal government – move water from the mountains of the north to the farms and cities in the south. The keystone reservoirs for each system are 36 percent full. Water allocations will certainly be cut.

In its initial assessment, open to revision if the winter is wet, the federal Bureau of Reclamation reported that it will deliver just 5 percent of the supplies that have been requested by those who have contracts with the federal Central Valley Project. The blow would fall hardest on farmers, who are already lobbying for state and federal drought aid and a suspension of environmental rules that protect river flows. Municipal use, too, will be affected. Cities in the Sacramento region ordered mandatory water cuts starting in December, unusual for the wet season.

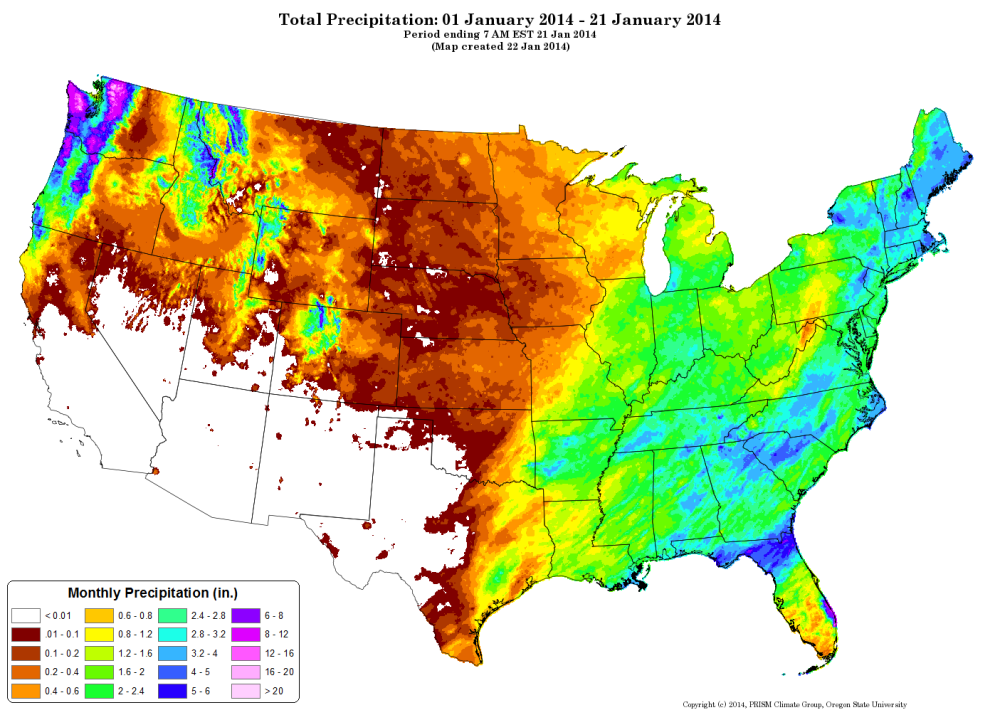

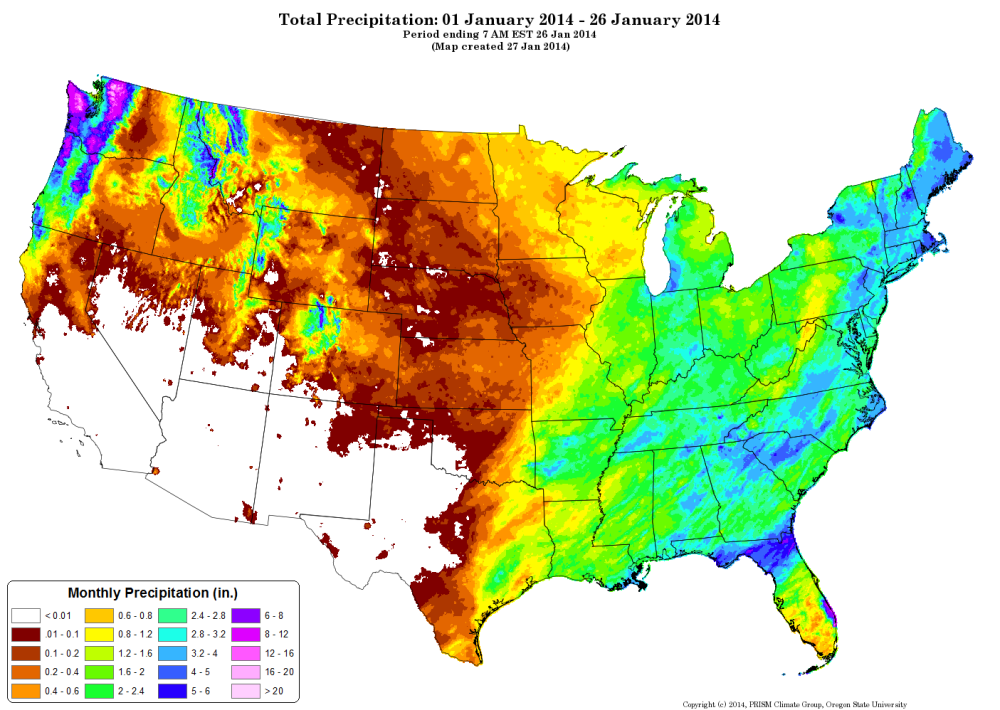

Almost no precipitation fell in January. Snowpack in the Sierra Nevada is just 15 percent of normal, meaning that depleted reservoirs are not likely to get a boost from runoff during the spring melt.

“It will be an eventful year.”

–Jay Lund, director

Center for Watershed Science, UC Davis

In response, both the governor and the state Department of Water Resources have set up drought-management teams. State officials are hoping to facilitate transfers of water between willing buyers and sellers to move water where it creates the most economic value.

Besides transfers, groundwater is another way to cope with scarce precipitation. Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Science at the University of California, Davis, told Circle of Blue that the state usually endures one or two dry years by drawing down reservoirs. Once the reservoirs are depleted – as is now the case – farmers and cities pump water from aquifers.

But even that strategy has limits – limits that California may be reaching. Satellite data released this week shows that groundwater reserves in key watersheds on a steady decline. In November, the U.S. Geological Survey published a report showing that rampant groundwater use in the Central Valley is causing the land to sink, thereby threatening the structural safety of a major canal. An investigation last year by The Desert Sun newspaper found water levels declining in 62 percent of 3,394 wells in central and southern California. Calls for stricter state regulations regarding groundwater will get louder in 2014.

These physical changes to the state’s water resources are taking place at the same time that state officials are stumping for a $US 25 billion tunnel system to route water through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. In theory, the apparatus would increase the amount of water that is available both to Central Valley farmers and to the Delta ecosystem, where endangered fish species live. The price tag — equal to the total economic output of Jamaica — has caused many in the debt-soaked Golden State to blanch, even without counting the cost of borrowing money. Adding interest, the total bill could double at a minimum, reports the San Jose Mercury News.

Politicians are also negotiating a bond measure for water infrastructure, planned for the November ballot. Twice delayed because of fears about its cost, the measure will likely be cut in half from the original $US 11 billion proposal.

Add in local debates about flood control, designation, and quality of drinking water, and Californians will have no shortage of water issues to discuss.

“It will be an eventful year,” Lund said.

Texas: Wet, But Still Dry

Last fall, deluge after deluge swamped central Texas, bringing temporary relief to a region that was approaching its worst drought on record. The rains, however, largely fell where the reservoirs are not. At the start of 2014, the region’s water supplies are in a perilous condition.

Home to 840,000 people, Austin gets its drinking water from the Lower Colorado River Authority, which operates six reservoirs upstream of the Texas capital. The two largest reservoirs are less than 38 percent full. If they drop below 30 percent, a new drought of record will be declared, a move that would reduce the amount of water that cities and industries are guaranteed. That possibility has pushed local governments to look for alternative supplies, most notably to groundwater districts which are signing off on new permits to pump more water from their aquifers.

LCRA also provides water for rice farmers along the Texas Gulf Coast. It seems likely, though, that the farmers will receive no water at all for the third consecutive year.

In San Antonio, just 128 kilometers (80 miles) from Austin, the water source is completely different, but the scenario is similar. The country’s seventh-largest city got 82 percent of its water last year from the Edwards Aquifer, the most important groundwater source in central Texas. The aquifer feeds the region’s rivers, sustains several endangered beetle, fish, and salamander species, and provides drinking water to millions of people. And like the LCRA reservoirs, the Edwards Aquifer is also nearing historic lows.

“Usually, winter is a recovery period for the aquifer. [Winter drought restrictions] just never happen here.”

— Anne Hayden, spokeswoman

San Antonio Water System

Six weeks ago, the authority that manages the aquifer moved to ‘stage three’ of its drought plan, an action never before taken in the month of December. Since then, conditions have improved slightly, but water users are still required to cut withdrawals by 30 percent. Given the region’s recent dryness, the restrictions were not a total surprise — but they are unusual.

“Usually, winter is a recovery period for the aquifer,” Anne Hayden, spokeswoman for the San Antonio Water System, told Circle of Blue. “[Winter drought restrictions] just never happen here.”

San Antonio, to its benefit, has alternatives: recycled wastewater, surface reservoirs, and surplus water that is stored underground during the wet years. Hayden said that the restrictions may be more difficult for smaller communities who might not have such a diverse water-supply portfolio.

Rather, some of those small communities might want to dip into a pot of state money that is earmarked for water projects. In November, voters passed Proposition 6, a ballot amendment establishing a $US 2 billion water fund. The state’s 16 water-planning regions will spend the first half of 2014 making a wish list and ranking the projects for which they want funding.

Due in June, those lists will be sent to the Texas Water Development Board, the agency that is responsible for doling out the low-interest loans. The TWDB will craft its own scorecard for evaluating the projects, which will be submitted by region. State law sets at least a dozen criteria that the TWDB must consider, criteria such as an equitable spread between regions, cities, and towns. In other words, not all the money will go to Dallas or Houston. In fact, by law, at least $US 1 in five must be spent on water conservation, and $US 1 in 10 must go to rural areas.

The state’s scorecard is due by March 2015, when the fund is eligible to begin handing out loans. But Merry Klonower, TWDB spokeswoman, told Circle of Blue that “the board’s intention is to finish earlier than that.”

Colorado River: An Icon Under Pressure

The most evocative river in the Western United States is always the center of attention for the seven states that fall within its watershed. But with a first-ever water shortage on the horizon, water use and supply will face more scrutiny in 2014 than ever before.

The amount of water that is stored in the reservoirs of the Colorado River is the lowest since 1963, the year when Lake Powell — the last large reservoir built in the Basin — began filling. Total storage in the Basin today is just 49 percent of capacity, down 6 percentage points in a year.

This winter, the cognoscenti will keep one eye on the river’s Rocky Mountain headwaters. If the snowpack is paltry, a shortage declaration could come in 2016. Coping strategies such as pumping more groundwater and fallowing farmland mean that, in the short term, a shortage will be more a psychological threshold than a physical constraint.

“We’re looking at the hydrology and seeing the drought continuing and river levels continuing to drop.”

–Scott Huntely, spokesman

Southern Nevada Water Authority

The other eye will be trained on Las Vegas, where engineers are hurriedly building two emergency tunnels that will keep water flowing to Las Vegas, even if Lake Mead, the source of 90 percent of the city’s water, drops below the two existing water intakes. One tunnel is the so-called “third straw” – a third water intake, being drilled through bedrock into the deepest depths of the lake. Under construction since 2009 and often delayed because of technical challenges, the $US 817 million intake is scheduled for a completion date of spring 2015.

“We’re looking at the hydrology and seeing the drought continuing and river levels continuing to drop,” Scott Huntley, Southern Nevada Water Authority spokesman, told Circle of Blue.

Last year, engineers began building a smaller connector tunnel, designed to buy time until the third intake is ready. The $US 12 million project, scheduled to be completed this April, is a bit of a tangle: the first intake is being connected to the third, which will allow Las Vegas to use the second intake’s pumps to operate the first intake. The upshot is that the first intake, which provides half the city’s water, will be operable when Lake Mead’s surface elevation is 320 meters (1,050 feet). At current rates of depletion, however, the first intake would be sucking air within two to three years.

Las Vegas will also lose its most powerful voice for water. Pat Mulroy, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and a major player in Colorado River negotiations, will retire in early February. John Entsminger, a deputy general manager, has been appointed her successor.

Even if most of the talk in the Basin will be about shortage, snowpack, and restrictions, a small ecosystem revival is about to take place. Formerly a bird watcher’s delight, the Colorado River Delta — where the river meets the Gulf of California — is nearly dormant today. Little water has flowed through the marshes since 1998, but that could change in 2014.

In November 2012, Mexico and the United States signed Minute 319, an agreement that includes a provision to seed the Colorado River Delta’s restoration. Soon, the United States will release a one-time tidal wave of water called a “pulse flow” through the delta. Rose Davis, spokeswoman for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado River office, told Circle of Blue that a draft plan is due by January 31. If the plan is approved, U.S. and Mexican officials hope to begin the high-volume water release in late March, Davis said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Brett,

I agree that the Southwest is going to have a hard time with water this year. Since we are starting at record lows at the beginning of the year it will be important to start saving water early this year, and really it should be done year round. Here is a 5 yr old boy saving water with new technology. http://www.waterselect.com/how-it-works.html

Great synopsis, as always. These next few years should see many debates with regard to the Western States exporting crops that are water intensive. I was surprised to learn that 50% of the rice grown in the Sacramento area is exported to Japan. This crop requires an estimated 2.1 MAF/year.

http://calrice.org/pdf/Sustainability+Report.pdf

This recent drought will have a lot of people rethinking these crop strategies.

Informative article, Mr. Belford, thank you. The heavy rain throughout Northern California and the two+ feet of snow in the Sierra this month (February 2014) broke the record drought and we’re all hoping for more wet storms to follow. When California Governor Jerry Brown declared a drought emergency, I expected counties and cities to respond quickly with mandatory water conservation dictates, as in past years. So far, nothing anywhere in the state, which continues to surprise me. We need permanent, mandatory water conservation rules and penalties.

Brett,

Maybe work is already being contemplated, but this seems like an excellent time to fire up some earth moving machinery and reduce the accumulated siltation of our reservoirs. That would increase storage capacity on the cheap – we might even be able to dig a little deeper in some areas.

Carlo

Thanks for a better understanding of why the last year we had, a wet one by usual standards, hasn’t re-charged the aquifers. I have lived in Texas 20+ years and the pattern i have noticed is two dry years for every wet year. Un til this last year the wet years would generally save us for a time but he cumulative effect of the tendency towards really dry years has reached the point we would need a second wet year, which does not seem to happen often.