India’s Water, Food, Energy Conundrum: Conclusions From a Two-Year Reporting Project [Part 1 of 2]

For two years, the Wilson Center and Circle of Blue have explored the contest for food, water, and energy in India and the troubling ways it plays out across the country.

By Michael Kugelman

Asia Program at the Wilson Center

We chronicled the Pyrrhic agricultural victories in the breadbasket state of Punjab, where farmers are provided free water and energy that yield huge grain surpluses. This subsidy, though, also drains groundwater reserves with over a million powerful electricity-devouring water pumps.

We described India’s coal paradox. India is a nation rich in supplies of indigenous coal but unable to develop them efficiently. One big challenge is finding sufficient water to keep coal-fired power plants humming. In the coal-belt region of Chhattisgarh, many farmers worry new plants will divert precious river water. Meanwhile, as we chronicled in the short film Broken Landscape, local communities in the coal-rich state of Meghalaya complain that rat-hole coal mining has befouled the environment. A recent government ban on the practice has pitted powerful mine owners and their wage laborers against locals faced with coal-infested rivers and wells.

And we illustrated the climate-related threats to dams in India’s Himalayan states. We directly observed how a June 2013 flood wrecked new and existing hydropower projects in Uttarakhand, with major implications for India’s efforts to increase supplies of electricity, efforts meant in part to compensate for energy- and water-wasting agriculture in Punjab.

These examples highlight the challenges India faces in securing adequate supplies of food and energy in a century of rapidly changing environmental and economic conditions. Within each sector – food, water, and energy – can be found many more challenges, from insufficient food storage facilities and contaminated drinking water, to huge losses in energy transmission and distribution. Just as significant is India’s struggle to develop state and national strategies to address these challenges.

In the fall of 2014, we interviewed a number of India’s top natural resource policy experts to help us identify the most fundamental natural resource governance-related challenges; why they have arisen; and how they can be resolved. In essence, how can India’s natural resource management be more efficient and effective so as to mitigate growing food-water-energy choke points?

The various dimensions of India’s natural resource conundrum can be broadly grouped into three categories.

Supply Crunches

India is not a resource-scarce nation. Our “Choke Point: India” reporting found that India’s reserves of water, fertile land, and indigenous energy are ample. Yet supply cannot keep up with prodigious demand. India’s ravenous resource appetite can be attributed to rapid population growth, a growing economy, and vast agricultural needs. Water is a particular concern. “We are moving from a water-stressed to water-scarce situation,” warns Joydeep Gupta of The Third Pole Project.

Girija Bharat of The Energy and Resources Institute says the gap between water supply and demand is expected to be 50 percent by 2030. “We have sufficient water for our current needs, not future needs,” says Arunabha Ghosh of the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water.

Weather-related factors are a major long-term threat to supply. South Asia is unique because almost all of its freshwater replenishment comes during just four months of the year. Unlike Europe, which receives moderate yet year-round rainfall, South Asia receives only 100 days of annual high intensity rainfall during the monsoon season. Storing water is a major challenge – especially because India’s rapid urbanization is leading to the neglect and deterioration of aquifers, ponds, and wells. “When it comes to water,” Bharat says, “there are not adequate storage structures for it.”

Inefficiency

Our interviewees spoke repeatedly of the tremendous waste and loss of water and energy. Agriculture was singled out as India’s most resource-inefficient sector, due to the massive energy subsidies given to farmers to allow their electric pumps to access groundwater year-round. Pumps operate even when land isn’t being farmed. “Providing free power to farmers is one of the worst things politicians could have done to this country,” laments Gupta. In effect, says Ajay Mathur of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency, “there are no incentives for efficient use of energy.” The result? Four Indian states – including Punjab – have extracted 100 percent of their groundwater resources.

Another problem is significant losses during water transfers. According to Bharat, the public utility that supplies water to New Delhi loses around 50 percent of its treated water due to poorly maintained transmission lines.

The experts with whom we spoke believe water in India should be priced according to a volumetric tariff, which would provide public utilities with more revenue to upgrade infrastructure and lead to lower transmission losses and better efficiency. Other voices in India, however, argue that water is a basic need and that public authorities should not charge for it. Efficiency can be improved through other policy changes, they contend, from more use of drip irrigation (which uses less water than more traditional flood irrigation) to an emphasis on conservation measures such as rainwater harvesting. Either way, the challenge with water and energy, in the words of Ashok Khosla of Development Alternatives, is “to find the balance between improved efficiency and equitable distribution.”

The critical importance of natural resource availability – and of securing access to existing resources – cannot be overstated. Despite valiant efforts over four decades, India is not close to supplying enough energy to meet demand. Securing electricity for the 300 million or so people who don’t have it can help reduce poverty, strengthen health, allow for more hours to study or work, enhance cooking and food storage facilities, and improve agricultural and manufacturing techniques that can in turn drive productivity and wages upward.

Energy transmission losses are also huge. A quarter of the limited power that India generates is lost in an unwieldy and aging transmission grid, and 10 percent more is stolen. The result in almost every corner of the country is brownouts and blackouts. Businesses and residential consumers turn to diesel generators, which are steadily draining the national treasury by requiring ever-higher levels of diesel fuel imports. The noisy and polluting diesel generator is such a ubiquitous part of India’s national fabric that Bollywood uses it as a plot line.

Bureaucratic and Institutional Dysfunction

In India, natural resource policy responsibilities are held by multiple government departments and agencies. Generation, transmission, and distribution of energy are often carried out independently of one another, with no one government agency or institution accountable for the failure to provide reliable, affordable, and quality energy. Most if not all states in India have their own energy transmission agencies, which are networked into one of five regional grids. Encouragingly, these regional networks are being brought together into one national grid.

India’s new government, headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has proposed changes, such as consolidating some energy responsibilities into a Ministry for Power, Coal, and New and Renewable Energy. There is little precedent for such consolidation, however. Resistance from the energy sector bureaucracy could be strong, particularly from managers who stand to lose influence.

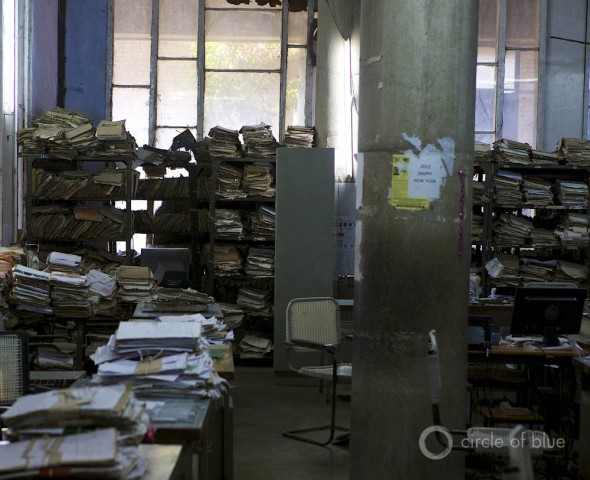

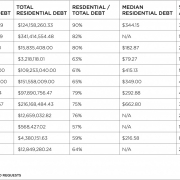

Additionally, many of India’s public sector entities which hold natural resource-related portfolios suffer from financial deficiencies. Experts with whom we spoke singled out the poor fiscal health of state electricity boards. These cash-strapped institutions, we were told, are now regarded as unviable and unprofitable, with major accumulated losses and liabilities. This has led to an inability to invest in better infrastructure, resulting in erratic power supply to consumers and high transmission and distribution losses. A striking example is in Tamil Nadu. In this southern and relatively prosperous state, the state electricity board is burdened by nearly $8 billion in debt that will require 100 percent financing from 17 banks to pay off. To be sure, these state struggles could complicate India’s efforts to establish a national grid.

Holding Development Back

These three challenges – supply crunches, inefficiencies, and sectoral dysfunction – are powerful forces restraining India’s development. Consider India’s 2012 power blackouts, which affected at least 600 million people and were blamed in part on a water-scarce monsoon season. Poor rainfall led to the excessive use of electric groundwater pumps for irrigation and reduced power production for hydroelectric power plants and conventional power plants. The blackouts cost hundreds of millions of dollars, adding to the financial miseries of the energy sector.

The severity of these challenges varies geographically, with agricultural and industrial usage patterns a key determinant. In heavily agricultural areas, inefficiencies are high – which is predictable given the consistently poor marks the agricultural sector gets for water and energy efficiency. In fact, in our conversations with experts, industry was described as quite efficient relative to agriculture.

Large industries pay a higher tariff for water and energy. So those resources are used relatively judiciously. Industry has also adopted more useful reforms than agriculture, we were told, and is easier to regulate than the more politically charged agricultural sector, which involves 700 million of India’s nearly 1.3 billion people.

More broadly, urban areas face different types of challenges than do rural areas. In Indian cities, says Varad Pande of Dalberg Global Development Advisors and New York University, a chief focus is on how to build infrastructure at an affordable cost. In the countryside, there is more of an emphasis on how to enhance access to natural resources.

Why Does This Happen?

A simple objective has traditionally driven natural resource policy in India: Produce as much as possible for as many as possible. This policy amounts to treating finite resources as if they are infinite. It is a model that helps explain the yield-boosting yet chemically intensive and water-inefficient industrial agricultural practices of the 1960s, the construction of large dams, and the large-scale importation of hydrocarbons from abroad. It is politically expedient, delivering the proverbial “goods” to politically significant constituencies, such as farmers.

But it is a 20th century construct – at home alongside mega projects, rapid growth, and rising productivity – that does not fit the resource-constrained, climate-changed, population-exploding conditions of the 21st century.

Incentives to produce plentifully in India mean there is little policy emphasis on the smart governance of natural resources. These include, above all, the importance of using existing resources judiciously. “My principle advocacy,” says Ramaswamy Iyer of the Center for Policy Research, “is that the trouble lies not in supply, but demand. We need to restrain demand.”

Iyer speaks in reference to water, but the same can be said about energy. The country’s prevailing supply-side focus deemphasizes other resource governance issues such as pricing, along with infrastructure repair and maintenance. The model taxes supplies, leads to losses and inefficiency, and generally accords little attention to the institutional incoherence and dysfunction that afflicts public sector natural resource bureaucracies.

A more inclusive approach to natural resource management will be critical to ensure a sustainable growth path for India. An inclusive approach means, in essence, embracing models that more fully incorporate demand side machinery and push for greater efficiencies. Above all, such steps will entail a shift in natural resource policies, pricing, and management.

Despite how well tread it is by other developing countries, it doesn’t take much to recognize the highly problematic consequences of India’s current development path – a path characterized by resource-intensive drive for growth and large state-led infrastructure projects. It has led to unregulated urban development, urban air pollution levels that rival and at times even surpass those of Beijing, inadequate infrastructure, and rapidly depleting resources. It has also contributed to declining GDP, which has fallen from about nine percent in 2005 to five percent in 2013.

So what can be done to untangle this food, water, energy knot? Stay tuned for part two as we continue our dive into the results of “Choke Point: India.”

Michael Kugelman is the senior associate for the Asia Program at the Wilson Center. Ferzina Banaji is the communications manager for the Climate and Energy Program at the World Resources Institute.

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Aditi Sahay, a New Delhi-based consultant who conducted the majority of the expert interviews for this article, and thank those who agreed to be interviewed: Girija Bharat of The Energy and Resources Institute; Chandra Bhushan of the Center for Science and Environment; Arunabha Ghosh of the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water; Joydeep Gupta of the Third Pole Project; Ramaswamy Iyer of the Center for Policy Research; Ashok Khosla of Development Alternatives; Ajay Mathur of the Burea of Energy Efficiency; Varad Pande of Dalberg Global Development Advisors and New York University’s Center for International Cooperation; and Lydia Powell of the Observer Research Foundation.

Sources: Business Standard, Central Ground Water Board (India), International Energy Agency, The Wall Street Journal.

Video: Sean Peoples and Michael Miller/Wilson Center.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

An excellent understanding of Water scenario in india . Well right now the situation is not bad but if not taken care soon it will turn in to a great National issue .We are to bring the concept of water Harvesting ,based on water cycle . The approach should be optimize use (excluding drinking and cooking need) ,recycle /reclaim and conserve /store . It is probably a cheaper solution then optimizing Energy but it requires involvement at every level . I am operating a PPP model in one of town in India with 0.2 m people and feel that @80 to 100 lpcd is good enough for decent leaving however the biggest worry is NRW / poor payment and bad condition of distribution system . In my opinion water should not be free but should be levied at optimum and this is possible by reducing use and eliminating Loss thru leakages etc