Israel’s Mediterranean Desalination Plants Shift Regional Water Balance

Desalination could remake the region’s politics and ecology. It hasn’t yet.

A half century ago, Israel built canals to move water from the Jordan River to the coasts. Today, coastal desalination plants send fresh water inland. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

TEL AVIV, Israel — The water that flows into Sorek desalination plant is drawn from near the Mediterranean Sea floor. Pumped inland, the water is cleansed, step by step, of salts and impurities. The transmutation does not take long. Forty minutes after entering the facility, the stuff of sailboats and sunbathers is now drinkable.

Sorek is the newest of five Israeli coastal desalination plants. A national mission in the last decade to develop the fleet, plus many more years of investment in wastewater recycling facilities, have turned Israel into as much a water producer as a water consumer. Nearly half of the country’s water supply is now manufactured, either by desalting the Mediterranean or purifying urban sewage.

Engineers, academics, and environmental campaigners see Israel’s water technology, including its advances in farm water use, in near Utopian terms: as a way to break free from a harsh geography, as a path to peace, and as an opportunity to rectify a history of environmental harm and political strife that stems from reliance on the Jordan River and mountain aquifers. In effect, rather than serving as the source of more conflict, deploying technology to increase the supply of fresh water in the Middle East could serve as a hopeful tool to achieve peace and to adapt to a drying climate.

But while the rapid construction of desalination plants, water recycling facilities, and other innovations strengthened Israel’s water security and garnered international acclaim, the grand vision of the optimists is impeded by the myriad ecological, economic, and political realities of the present. And the stresses of that present swirl around the region’s vital sources of surface and groundwater — principally the Jordan River, which forms the boundary between Israel and its neighbors.

Simply stated, the ecological and political condition of the Jordan River basin is dreadful. Regional tension, ever present between Israelis and Palestinians, surfaced again in recent months as West Bank villages accused Israeli authorities of cutting water supplies during Ramadan, the holy month of fasting. Israel asserts that Palestinians refuse to cooperate on repairing leaky pipes.

The ecological damage in the region is also severe. The Dead Sea, at the end of the Jordan River, is drying. Water levels are dropping by 1 meter (3 feet) per year because of water diverted upstream. The country’s rivers and springs, some of which tumble through deep chasms to feed the Dead Sea, are polluted and depleted. At times the Jordan resembles a drainage canal, soiled and fetid.

Outside the Jordan Basin is Gaza, which also is a disaster. Groundwater, the main source of public supply for 1.8 million Palestinians in Gaza, is so saturated with nitrates and bacteria from sewage and with chlorides from encroaching seawater that it is nearly undrinkable.

So much in the Middle East is a matter of perception. With water it is no different. The technological optimists speak of water abundance resulting from the country’s desalination facilities, sewage recycling, and commitment to efficiency that cuts waste from leaky pipes. Water authorities reject that notion.

“I disagree completely,” said Uri Schor, spokesman for the Israel Water Authority, when asked about water abundance. “We have the capacity to produce water, but we do not have more water than we need. We don’t have enough water for the people who live here. It doesn’t matter how you divide it. People need more than the natural resource.”

But share it they must, the Israelis, Jordanians, and Palestinians. Even the Syrians, who draw water from the Yarmouk, a Jordan tributary.

The sides are basically bound together, said Aaron Wolf, an Oregon State University professor who is often involved in Jordan Basin negotiations. He compared the region’s water network to the human circulatory system. “There are pipes going everywhere,” Wolf said in an interview with Circle of Blue. “You couldn’t make unilateral systems just as you couldn’t isolate the veins in the left arm from the rest of the body.”

Water As Source of Peace

Diplomacy has shown itself to be incapable of bridging the political gulfs that are open between Israel and its neighbors. Water, say engineers and specialists, could prove more effective. Israeli water technologists argue that because the region’s water distribution system is so tightly woven, desalination and wastewater recycling open the possibility of trades.

Farm fields spread across the lower Jordan River Valley. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

It’s all about supply. More water produced on the coast allows for less water to be drawn from the Jordan. That also means more water to replenish the Dead Sea, and more water allocated to Palestinians.

Uri Ginott, government relations manager for EcoPeace Middle East, the region’s leading environmental organization, compares the Jordan River Basin to Europe after World War II. There, a common coal and steel market between former combatants forged economic bonds that nurtured political union. Here, water could play the same role, he argues.

“Desalination is turning the water issue from a zero-sum game to a win-win,” Ginott told Circle of Blue. “Every drop doesn’t have to come at the expense of another.”

Aaron Wolf, the Oregon State professor, says that desalinating water from the Mediterranean relieves pressure in the basin’s highly integrated water network. “Desalination means a lot less stress on the mountain aquifer shared between Israel and Palestine,” Wolf told Circle of Blue. “It frees more of the groundwater to be managed by Palestinians. It allows for some increase in instream flows for the lower Jordan River and the Dead Sea. It means less stress throughout the system.”

Some trades are already being discussed. A controversial plan to halt the decline of the Dead Sea calls for exchanges of water between Israel and Jordan via a desalination plant on the Red Sea coast. The salty brine that is left over from the process will be piped into the Dead Sea.

Sunrise over the Dead Sea is veiled by haze. What to do about the shrinking sea is a top water policy question in the Jordan River Basin. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Rivers are in the conversation, too. In 2012, Uzi Landau, then Israel’s water and energy minister, announced a national river restoration plan, arguing that because desalination had lifted Israel out of water crisis, officials now needed to return water to rivers. “We have no other country,” Landau said, describing rivers as the hardening arteries of Israeli’s water economy.

Green groups, while praising success stories such as the rejuvenation of the Yarkon River, which flows through Tel Aviv, say that the national river plan is more talk than action. The Dead Sea continues to wither as it awaits an emergency infusion of Red Sea brine. Relations with the Palestinians are lukewarm and then frightfully cold. Achieving peace and ecological balance from the technological wonders will require a defter political touch.

Desalination Nation

The Jordan River is lively on a hazy Shabbat morning in early April. The Jewish day of rest draws a crowd to a stretch of water where the holy river exits Lake Kinneret, in northern Israel. Pilgrims dip their heads into eddies at Yardenit, a baptism site with a parking lot scaled for bus tours. At Rob Roy, a riverside sports outfitter, families in orange life jackets rent canoes and zig zag in the slack current. On the banks, young couples strum guitars while a group of teenagers, their voices flitting between English and Hebrew, leap into the water.

Water was a priority for Israeli authorities from the beginning, and, like the holiday revelers, it was to the Jordan River that they turned.

“The only way to establish this nation was if we provided enough water for everyone,” says Noam Weisbrod, director of the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research. Israel’s rainfall patterns resemble California: wetter in the north and in the Judean Mountains, and dry in the south, where the Negev desert accounts for 60 percent of the country’s land mass. Wetter, but not soaked. The northern end of Lake Kinneret and Ramallah, in the West Bank, receive 67 centimeters (26 inches) of rain per year, about as much as eastern Nebraska. These amounts will surely diminish in the future. Climate models show a drying trend in the eastern Mediterranean.

A teenager balances on a slack line stretching across the Jordan River, near Lake Kinneret. Though monumental in history and politics, the Jordan is not a large river. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Almost immediately after independence in 1948, David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister, called for a canal that would redistribute the Jordan. A national water plan drawn up two years later intended to swallow the river — not all but a sizeable portion — punch wells into aquifers, and deliver water to the urban coast and the lonesome desert. The National Water Carrier, the largest infrastructure project in the country’s history — and its most important, according to Weisbrod — opened in 1964.

The canal angled westward to Tel Aviv then south to the arid Negev, and it turned Lake Kinneret, also called the Sea of Galilee, into a matter of national security. During drought, lake levels were a nightly fixture on news broadcasts, just as stock prices are featured in the United States. If the lake dropped too close to predetermined “red lines” — or even below, as happened in 2009 — withdrawals would be restricted.

Even before the drought, Israeli officials decided a new source was needed. Engineers in the Negev had experimented decades earlier with techniques to purify salt water. One of them was Sidney Loeb, the inventor of reverse osmosis, a desalination technology that uses pressurized chambers to produce fresh water. Materials in the chamber called “membranes” trap salts but allow water molecules to pass through. In 1968, Loeb installed a reverse osmosis unit at Kibbutz Yotvata, a farm community in the Negev. The unit produced 200 cubic meters of fresh water a day from brackish aquifers and was the second reverse osmosis facility in the world.

Loeb’s first fruits blossomed into an industry. Today, five big desalination plants line Israel’s Mediterranean coast. Ashkelon, the first, opened in 2005. Sorek, the most recent, opened in 2013 and is the world’s largest seawater reverse osmosis facility. Combined, the five plants produce roughly 550 million cubic meters per year (145.3 billon gallons), accounting for one-quarter of total water use — more than double what is drawn from Lake Kinneret.

To the engineers, the Mediterranean facilities are a triumph.

Desalination helps Israel “to be independent from climate and rainfall,” Boris Liberman, chief technology officer at IDE Technologies, which built Sorek, told Circle of Blue. Liberman recalled the days when the Sea of Galilee levels were a daily conversation. “Now, it’s out of the news,” he said.

To others, the membrane technology that powers the plants is an instrument of peace. Uri Ginott of EcoPeace Middle East talked about water as the currency of cooperation in the region. Edo Bar-Zeev, who does membrane research at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, says that collaboration between Israeli companies and water-scarce regions can be a “path for peace.” Uri Schor, the Israel Water Authority spokesman, called the country’s technical know-how a “bridge for peace.”

The Jordan River downstream of Lake Kinneret resembles a drainage ditch. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

The view is not shared by all. Groups working in the West Bank say that Palestinians have not reaped the benefits of Israel’s desalination plants. They would prefer more control over the water beneath their territory. The Oslo II agreement signed in 1995 gave Israel rights to 80 percent of the groundwater beneath the West Bank.

“There is no direct change in relations related to the building of desalination plants,” Abdelrahman Tamimi, director of the Palestinian Hydrology Group, a research organization, told Circle of Blue. Instead of discussing equitable access to water, the Israelis would prefer selling desalinated water to the West Bank, he said. “They want the Palestinians to be a customer rather than a citizen in our own country.”

The political stalemate is seen in other ways. The Joint Water Committee, which is supposed to coordinate water projects between Israel and Palestine has not meet in five years. Both sides blame the other for the impasse.

Misery by the Sea

One weak spot in Israel’s desalination plan is Gaza, the coastal enclave that is home to 1.8 million people.

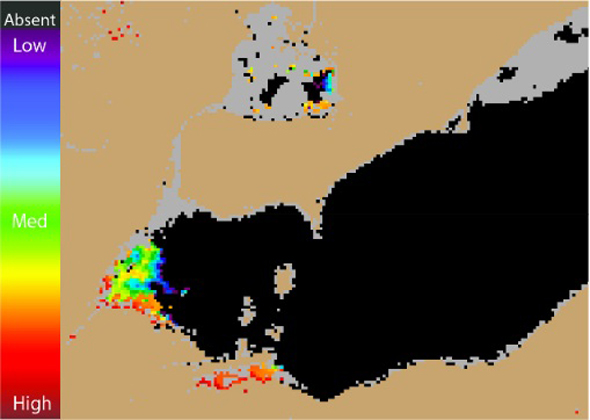

Gaza dumps up to 90 million liters (23.8 million gallons) of untreated or partially treated sewage into the Mediterranean every day because of insufficient electricity, inadequate facilities, and poor management. An Israeli blockade prevents or impedes the import of pumps, disinfecting chemicals, and other building materials, for fear that Hamas, the party that controls Gaza, will use them to wage war against Israel. The split in Palestinian leadership between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority (PA), which controls the West Bank, causes self-inflected wounds. In April and May, Gaza’s only power station shut down because it could not afford fuel due to a disagreement with the PA over tax payments, according to the United Nations. The four wastewater plants in the territory could not treat sewage.

Without treatment, the sewage pollutes the coastal aquifer, the primary water source for Gaza. It also travels across borders. Israel’s Ashkelon desalination facility is 6 kilometers (4 miles) from Gaza. Ashkelon shut down for four days in February due to pollution in the Mediterranean.

Desalination could be a water supply option for Gaza. The territory has the coastline and the need. What is does not have, according to Tamimi, is reliable power, the ability to pay, or the capacity to manage the project. “Municipalities are not even able to collect rubbish,” he said.

Even so, a European Union-funded desalination plant is under construction in southern Gaza that will supply 75,000 people in the governorates of Rafah and Khan Younis.

The plant is being developed in three phases, each of which will cost $US 11 million. The first phase is expected to be completed by October, and the second some three years later. Solar panels will provide 12 percent of peak electricity and on-site generators will hedge against power outages, according to Catherine Weibel of UNICEF, a project partner.

The plant’s output — 6,000 cubic meters per day (1.6 million gallons) for phase one, or roughly one percent of Sorek’s capacity — is miniscule compared to the giants up the coast. But it could be the beginning of something larger.

The EU is discussing with the Palestinian Water Authority the development of a central desalination plant for Gaza, according to Inas Abu Shirbi of the EU Office for the West Bank and Gaza. An environmental review of a facility with a capacity of 55,000 cubic meters per day began this spring. A reliable supply of desalinated water will help replenish the badly damaged coastal aquifer, Weibel said.

Nature Comes Last

Highway 90, the only north-south route on the west side of the Jordan Valley, skirts the shore of the Dead Sea. Near Ein Gedi, a resort town and farm community, the road turns sharply inland over new pavement. It cannot continue on a straight path because of a hole in the ground. The two-kilometer bypass, which opened in July 2015, sidesteps a sinkhole along the main road.

The Dead Sea, shrinking because of upstream water withdrawals, has split into two basins. The canal in the foreground moves water from the northern basin to the south. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Sinkholes are a result of the shrinking Dead Sea, which is exposing salt caverns as it recedes. Fresh water percolates into the caverns, dissolving them. There are more than 5,000 sinkholes in the area, according to Yossi Yechieli, a researcher at the Israeli Geological Survey. Local newspapers report that power lines, bungalows, even hikers have fallen in the cavities.

Water levels in the Dead Sea have dropped 35 meters (115 feet) since the National Water Carrier opened, and are falling roughly 1 meter (3 feet) per year today. Yechieli said that to bring the sea back to its condition of 50 years ago, the upstream countries would have to stop pumping from the river and its tributaries altogether. “That is something Israel will not do,” he told Circle of Blue. “Jordan needs water too and will not stop pumping. Neither will Syria.” An EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East study in 2010 found that 98 percent of the historic flow of the lower Jordan River was diverted for domestic and agriculture use.

Instead of halting diversions, Israel and Jordan want to bring in reinforcements. Their $US 1 billion proposal, debated and studied for years, is a water and energy package: a desalination plant on the Red Sea coast, a pipeline to transport the brine to the Dead Sea, and hydropower stations to generate electricity from the 400-meter (1,312-foot) drop into the basin, the lowest spot on land.

The Red-Dead canal is an experiment with an uncertain outcome, Yechieli said. What the basin authorities are left with is a management decision: how much water to allocate to the sea. “Policy makers have to decide if it’s worth it,” he said.

Wolf of Oregon State University said restoring the sea is worth it for a number of reasons. The sinkholes damage roads and bridges. The receding shore is increasingly distant from the resorts and spas. And springs are at risk of drying up.

There are spiritual reasons too, he says. Not just for the Dead Sea, but for the entire lower Jordan. “This is a historic stretch of river that is holy to people of three faiths,” Wolf said. “People come to experience it as a river, not as a saline trickle.”

The Yarkon River, a restoration focus in recent years, flows through Tel Aviv. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Despite the slow pace of restoration, there is progress. The Israel Water Authority is putting 9 million cubic meters (2.4 billion gallons) per year back into the lower Jordan. “Until a few years ago people said it was not possible [to do this],” explained Ginott of EcoPeace. “The water authority needs to be commended for it.” Still, he said, that amount of water will not create the habitat to revive the river ecosystem. More water will be needed.

Other restoration projects draw praise. In Tel Aviv, the Yarkon River flows with treated wastewater, an urban renewal that recalls San Antonio’s famed Riverwalk, which also uses water that came from household drains. In the early morning, rowers ply the Yarkon on boats stored at the Daniel Rowing Centre. Joggers pass by on the banks.

“The Yarkon is a big success as an urban park,” Orit Skutelsky of the Society for the Protection of Nature told Circle of Blue. “It’s changed the climate of the city. In a dry country with limited water resources, that’s a success.”

Travel funding for this story came in part from the Murray Fromson Media Mission, sponsored by American Associates, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton