Lake Mead Drops But Hoover Dam Powers On

New investments expand the dam’s generating range.

Power lines sweep outward from Hoover Dam, the largest hydropower facility in the U.S. Southwest. Because water levels in Lake Mead have plummeted, power customers have invested in equipment upgrades that will keep the dam operating in low-water conditions. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

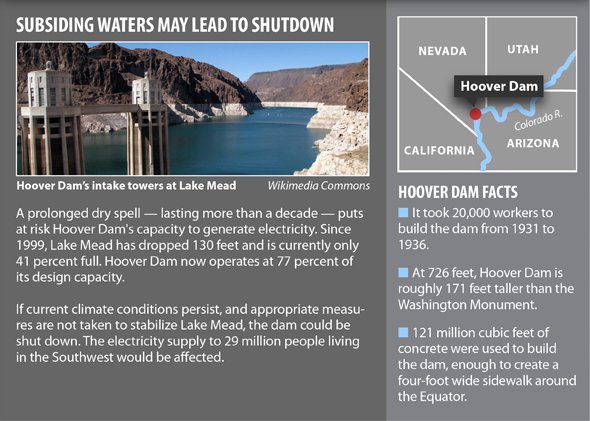

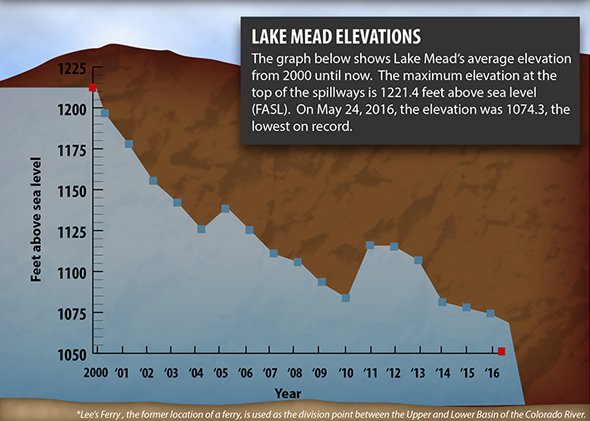

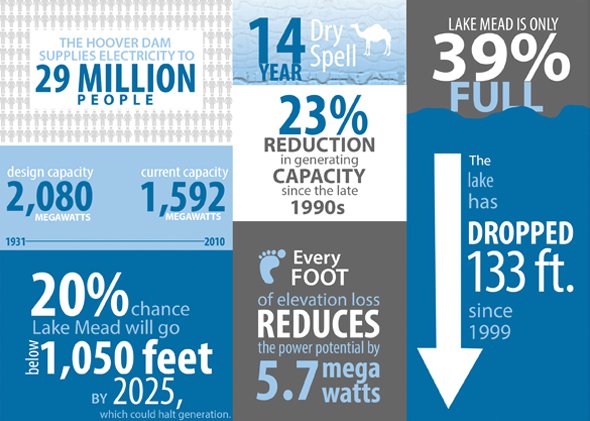

Six years ago, at the end of the summer of 2010, federal Bureau of Reclamation officials worried that Hoover Dam, the biggest hydropower enterprise in the Southwest, might soon go dark. Water levels in Lake Mead, the dam’s energy source, were falling, and Hoover was moving “into uncharted territory,” the facility manager told Circle of Blue.

Today, the story has a twist. Lake Mead is 10 feet lower, a new record set on May 18 that is re-broken every day now. Yet though water levels continue to decline, Hoover’s hydropower is in a much better spot. Thanks to investment in efficient equipment, managers are confident that they can still wring electricity from the Colorado River even as the surface elevation of Lake Mead drops below 1,050 feet, the uncharted territory that was assumed to be Hoover’s operating limit.

“As far as power goes, we can still operate below 1,050 feet,” Rose Davis, Bureau of Reclamation spokeswoman, told Circle of Blue. Dam operators are revising the lower limit to 950 feet, a boundary that will be confirmed in October once the fifth and final more-efficient turbine is installed, Davis said.

Hoover Dam’s Troubled Waters

Click the arrows to view the slides.

The investments in wide-head turbines, stainless steel wicket gates, and digital controls are emblematic of the types of practices that are necessary for the drying Colorado River Basin. In order to maximize scarce water, authorities must do more with less. Water managers in the lower basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada, keen to avoid a disastrous downward spiral for Lake Mead that would threaten supplies for tens of millions of people, are spending more than $US 11 million on farm-efficiency and other projects that will conserve water and bank the savings in Lake Mead. Dam managers and power customers are adopting the same ethic for power generation.

Spending to Save Water and Boost Power

Electricity from Hoover is some of the cheapest in the country, at 1.83 cents per kilowatt-hour. Constructions costs for the dam were paid off years ago and the energy source, the water, comes from Mother Nature free of charge.

Customers in Arizona, California, and Nevada, the destination for Hoover’s output, would like to keep the cheap power flowing. That is why they spent $US 14.9 million since 2011 on the turbines and wicket gates.

Maximum amount of power that the dam is capable of producing — is down 30 percent from when Mead was full. For every foot that Mead drops, generating capacity decreases by five to six megawatts. Money is power, the old saying goes. So is water.

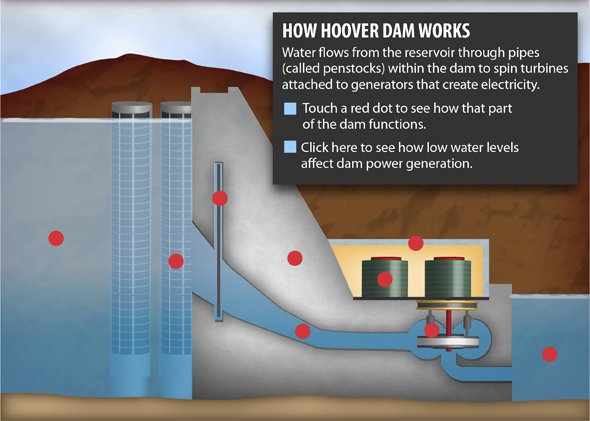

The problem with Mead’s low water level for power generation is physics. Pressure differences in the water coming into the generators produce air bubbles on the turbine blades. As the water flows across the blades, the bubbles collapse and burst, which causes vibrations that can damage the generating unit. If the vibrations worsen, the unit must be shut down.

Wide-head turbines are designed to avoid these “rough zones” and operate smoothly at low reservoir levels. Four of Hoover’s 17 turbines have been fitted with wide-head models, and a fifth will be installed by October.

The wicket gates, on the other hand, allow for more precise control of water flowing through the turbines. They also reduce water leakage so that every drop that passes through Hoover can generate as much power as possible. Digital controls, which allow for more precise positioning of the wicket gates, have been installed at Hoover as well as at Davis and Parker dams, downstream on the Colorado.

“Any efficiency in hydropower means more power for our customers,” Kara Lamb told Circle of Blue. Lamb is the spokeswoman for the Western Area Power Administration, which markets Hoover’s power.

Though Hoover will not shut down any time soon, low water levels still reduce its output.

Generating capacity — the maximum amount of power that the dam is capable of producing — is down 30 percent from when Mead was full. For every foot that Mead drops, generating capacity decreases by five to six megawatts. Money is power, the old saying goes. So is water.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton