As Global Poverty Rises, USAID Plans for Covid-Altered World

Ensuring that water, sanitation, and hygiene are threaded throughout the agency’s programs is key, observers say.

Women queue for water in New Delhi. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Those who were at the cusp of a better life are confronting an extraordinary reversal of fortune.

Until this year, extreme poverty had been steadily falling across the globe since at least the 1980s. At the same time, hundreds of millions of people had gained access to proper water and sanitation services.

The spread of the new coronavirus has upended those trajectories. The World Bank estimates that an additional 88 million to 115 million people will enter extreme poverty in 2020 because of the pandemic. It’s the first time in two decades that progress has reversed. The bank reckons that as many as 150 million people could be affected through 2021 if the virus is not tamed.

Those estimates are alarming to international development experts. The U.S. Agency for International Development expects “significant backsliding” for a host of indicators, from nutrition and food security to health and childhood education. For advocates of water, sanitation, and hygiene, there is fear that an increase in poverty will undo recent gains in access to those life-changing services as well.

“The reality of this is you don’t have 150 million people drop into extreme poverty within a year without significant global consequences,” Liz Marcey, director of policy and advocacy for WaterAid America, told Circle of Blue.

Marcey compared Covid-19 to HIV/AIDS, meaning that the disease and its consequences need to be incorporated into international aid work for the foreseeable future.

International development agencies like USAID are beginning to grapple with that conundrum. How do they adapt their poverty-reducing mission to a world beset by upheaval?

‘The Existential Requirement’

USAID gave a sneak peak of its plans in late October, when the agency released a “snapshot” of a strategy it’s calling Over the Horizon.

The seven-page document outlines three overarching goals: build stable, resilient civic and governmental systems in countries that have been shaken by the virus; respond to increases in poverty and declines in other indicators of wellbeing; and strengthen healthcare delivery.

Water — but not sanitation or hygiene — is mentioned under the second objective: responding to poverty. But Jim Barnhart was adamant that water, sanitation, and hygiene will be fully accounted for in the strategy’s implementation. Barnhart is the assistant to the administrator in the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security, which oversees the agency’s water work.

“I see WASH as the fundamental, the existential requirement for any place in which we work,” Barnhart told Circle of Blue, using the acronym for water, sanitation, and hygiene.

USAID and the State Department have already contributed $1.6 billion in emergency funding in response to the pandemic, providing items like ventilators, protective gear, and handwashing stations, as well as hygiene education. The Over the Horizon strategy takes a longer view, looking months and years ahead, Barnhart said.

There are many questions about how the plan’s aims will be converted into actions, Marcey said. She wonders how the plan will be integrated into existing country-level frameworks. She worries that the scale of problems unleashed by the pandemic could be an overwhelming force. Instead of strategic focus, the plan could unravel into a piecemeal approach.

But until the agency releases more details, Marcey and other observers can only speculate based on the “very bare bones” seven-page outline, which does not include priority countries. “We don’t know,” Marcey said about the plan’s implementation. “We just don’t know yet.”

Marcey noted that USAID, when it restructured last year, established the internal mechanism for coordination, setting up a WASH leadership council with high-ranking agency officials. But then the pandemic hit and the emergency response took priority.

Danielle Heiberg, advocacy adviser for Global Water 2020, which encourages U.S. government investment in water, sanitation, and hygiene, said that water ought to bridge programs. “We hope that WASH isn’t pigeonholed in that one objective, but that it does start to come out in these other objectives,” told Circle of Blue.

Chris Holmes was USAID’s global water coordinator from 2011 to 2017. Now an adviser with Boston Consulting Group, Holmes said that the agency has the leadership and expertise to carry out the task.

Most essential for water, sanitation, and hygiene will be ensuring that it is threaded throughout the agency’s mission areas and incorporated into health and education programs, he said.

A handwashing station in Mali. Photo courtesy of WaterAid/Guilhem Alandry

“What’s impressive about the report is they’re trying to identify as many possible considerations, see how they link so they relate to the objective of preventing the spread of Covid and dealing with the harm the spread has caused,” Holmes told Circle of Blue.

That harm can be measured at both the household and community level.

For households, the shuttering of businesses and government-imposed lockdowns have curtailed their income. This leads to difficult choices, Marcey said. Between food and water. Between food and soap. WaterAid launched hygiene campaigns to encourage people to prioritize soap when shopping. But Marcey acknowledges that even when that messaging is successful, it adds financial strain.

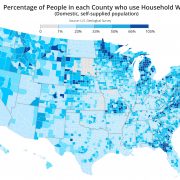

Barnhart said that USAID did phone surveys in five African countries to evaluate the strain. The agency found the trajectories revealed by the surveys “extremely alarming.” As many as 300 million people may already be facing difficulties in water access, he said.

“As income drops, households and businesses are struggling to afford water that is essential to everyday life and they’re missing payments,” Barnhart said.

Those individual struggles add up. At the community level, water utilities are financially stressed because fewer customers are paying their bills. The government of Kenya ordered utilities to continue water service and provide water for free to informal settlements, even though revenue was declining and operating costs increased. A trade group for Kenyan water providers estimated that revenue collection dropped to 30 percent between March and July.

Barnhart said that the crisis has created openings for reform. In conversations with colleagues in Jordan, where he served for five years as the mission director, Barnhart sensed an opportunity for legal, regulatory, and operational changes that would better position utilities for the future.

“Now is the time to make those changes because there was an openness at the highest political level that the pandemic was pushing us into reforms and streamlining inefficiencies that in normal days was a much harder slog,” Barnhart said.

USAID is shepherding that process in Nigeria, where the agency is working with local governments and banks to establish digital payment systems for water utilities. It’s more convenient for a generation used to transferring money on its phones, plus customers can make payments even in lockdown. A project in Niger State saw immediate returns as payment rates that had dropped in March began to rebound, according to a USAID spokesperson.

Others see opportunity in this crisis, too.

Marcey said that the pandemic is a reminder that healthcare cannot be separated from water, sanitation, and hygiene. That WASH not only prevents disease, but is also a foundation for economic recovery.

“My hope is that USAID takes this opportunity to expand its concept of global health security to include WASH and WASH infrastructure,” Marcey said. “That to me is one of the biggest lessons.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!