Perspective: How Does the Coronavirus Crisis Compare to the Global Groundwater Crisis?

Global efforts on the scale of those to curb the devastation of SARS-CoV-2 are few and far between. These months could provide a template for reducing future environmental damage.

Well drillers for Hydro Resources drill a well near Sublette, Kansas. Photo © Brian Lehmann for Circle of Blue

Xander Huggins, Tom Gleeson, Jay Famiglietti

Special to Circle of Blue

Amid the fear and uncertainty caused by the coronavirus pandemic, leaders are pointing out similarities with another global crisis. UN Secretary-General António Guterres and others have started to use the coronavirus pandemic as a warning for the ongoing and looming tragedies of climate change.

While such commentary reflects a position of privilege at a time when many people are most concerned with their health, their families, and their financial security in a shuttered economy, the coronavirus-climate change analogy is both tangibly poignant and deeply alarming. Yet another global crisis, however, is being left out of this discussion despite being linked to climate change and posing similarly global challenges. Groundwater, typically out of sight and thus out of mind, is being neglected — again.

To bring groundwater to the forefront, we highlight similarities and differences between the coronavirus pandemic and the global groundwater crisis.

Similarities

First, neither crisis should come as a surprise. Warning calls have long been sounded on both fronts. The most recent report from the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, which assesses readiness for global health emergencies, warned last September that “the world is not prepared for a fast-moving, virulent pathogen pandemic.” Bill Gates, meanwhile, decried pandemic blind spots in at least five interviews or public lectures in the last decade.

For groundwater, documentaries like Pumped Dry: The Global Crisis of Vanishing Groundwater have attempted to raise public awareness of the crisis, while articles on groundwater depletion and its consequences are abundant in scientific literature. To list just two:

- A 2014 commentary published in the journal Nature Climate Change warned that “groundwater is being pumped at far greater rates than it can be naturally replenished, so that many of the largest aquifers on most continents are being mined, their precious contents never to be returned.”

- And a 2019 study published in the journal Nature found that “by 2050, environmental flow limits will be reached for approximately 42 to 79 percent of the watersheds in which there is groundwater pumping worldwide.”

Decision makers cannot claim ignorance of either crisis — both infectious disease and water crises are found on the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report Top 10 risks by impact over the next decade.

A second similarity between the two crises are the links between local hotspots and global impacts.

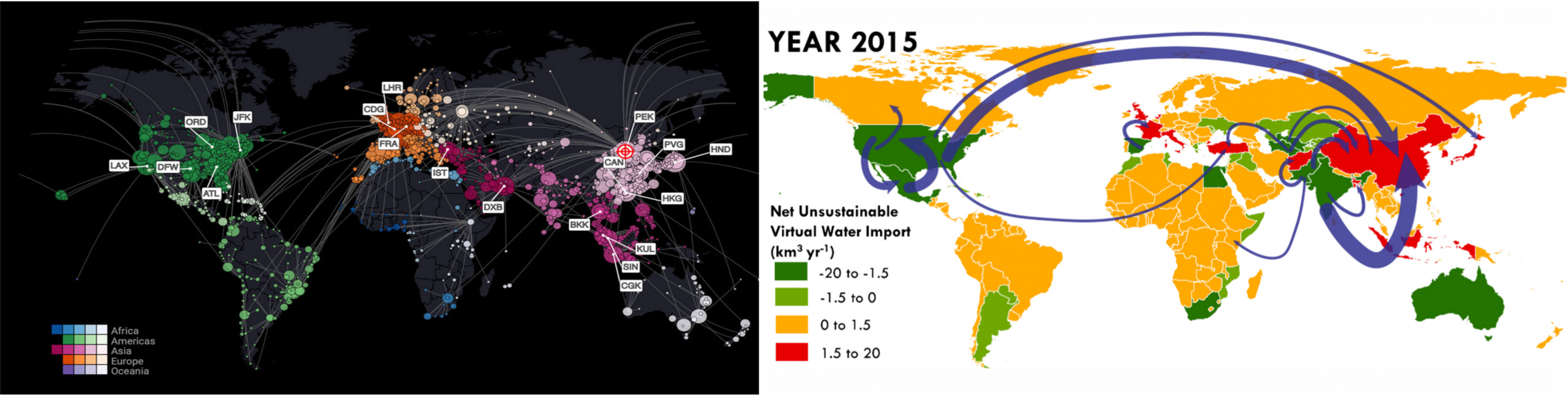

By now, you’ve probably seen some iteration of this coronavirus time lapse. The map shows virus hotspots initially in China that moved to Iran and Italy and now to nearly every country. Driven by human mobility, a local outbreak became a global pandemic. While the groundwater crisis is not contagious, countries are connected by the implications of unsustainable groundwater use. How does this work?

In this case, agricultural trade networks act as the vectors of transmission. Groundwater depletion in an agriculturally productive region manifests into food insecurity elsewhere when water levels drop below what is needed to sustain crop production and exports decline. This works in the opposite direction too, where food demand in one region can drive groundwater depletion in another.

On the left, tracking the probable transmission routes of the coronavirus, from a study led by the Robert Koch Institute. On the right, unsustainable irrigation water consumption embedded in agricultural trade, from a study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters in 2019.

Another critical similarity between the two crises is that they worsen existing inequalities. The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board warned that “the poor suffer the most” in disease outbreaks, while United Nations University research indicates that the pandemic could push half a billion people into poverty. Such precise predictions do not exist for the global groundwater crisis, but groundwater access has been associated with poverty alleviation in rural communities. Groundwater depletion may return households in these regions to poverty, especially poor families whose limited financial and technical resources limit their ability to adapt to falling water tables.

Responding to both crises will require prudent intervention. Already in the coronavirus response we can see that certain countries and regions reduced their fatality and transmission rates with proactive management and consistent messaging.

Differences

There are fundamental differences, of course, between the coronavirus and groundwater crises.

A dramatic difference is recovery time. While the end of the coronavirus pandemic is uncertain and social life may be altered for the foreseeable future in any circumstance, the dissipation of the outbreak will depend on two developments: achieving herd immunity or developing a vaccine. A conservative guess might place this return to quasi-normal life at more than one year away. In contrast, most of the world’s major aquifers recover much more slowly after decreases in pumping with response times that range from several decades to hundreds of thousands of years. Other negative side effects of unsustainable pumping can be permanent. If groundwater depletion causes land subsidence, the compacted land cannot continue to hold water. The storage capacity is lost forever.

Environmentally, the pandemic and the groundwater crisis have starkly different consequences. “Nature is taking a breath while the rest of us are holding ours” is how the Atlantic characterized the few environmental benefits of the global shutdown. Conversely, groundwater depletion contributes to global sea-level rise, diminishes river flows, and can result in the salinization of coastal aquifers. The coronavirus is a global human tragedy whose environmental benefits are but a small benefit, while the groundwater crisis harms society and the environment altogether.

Further, each crisis develops at vastly different rates. When left unchecked, the coronavirus is characterized by exponential growth in infection counts. Groundwater depletion, however, is relatively linear. The exponential growth of the pandemic has garnered the world’s attention — the term “flatten the curve” is almost synonymous with the pandemic itself. Humans are innately bad at understanding exponential growth, and thus the exponential characteristic of the virus has likely contributed to both the hysteria and notoriety surrounding the pandemic. So what does this mean for the groundwater crisis?

While pandemics have clear criteria classifying their phases, no strict criteria exist for the global groundwater crisis. If linear depletion trends are easier for the general public to understand, will we make better, less hysterical decisions for groundwater? Or will our comfort level with linear trends translate to general apathy? The linear rates of depletion in the world’s major aquifers pose a further uncertainty: whether global awareness and proactive intervention is possible for incremental environmental degradation. If societies are uncomfortable with the prospect of continued physical distancing to combat the coronavirus, this is a somber warning for the viability of steadfast collective action to address more persistent crises such as global groundwater depletion.

The graph on the left, from Our World in Data, shows the exponential growth in total coronavirus deaths. The graph on the right shows the generally linear trend in groundwater depletion for major aquifer systems, as noted in a study published in the journal Nature Climate Change in 2014.

Lessons

The existing social pushback to coronavirus response measures reaffirms the need for better groundwater crisis communication. If an immediate and exceptionally high level of personal risk isn’t enough to build consensus for the coronavirus, there’s little reason to believe such a consensus will take shape for confronting the global groundwater crisis.

Yet there is movement. A good place to start is the Global Groundwater Statement, a call to action on groundwater sustainability with three concise action items. To date the statement has over 1,300 signatories from over 100 countries. However, signing a statement is far from enough.

We should take heart in one clear lesson from the coronavirus: that we can slow the rate of change when we all work together. Global efforts on the scale of those to curb the devastation of SARS-CoV-2 are few and far between, and these months could provide a template for reducing future environmental damage.

Such collective action, were it to develop, could prove to be one of the few silver linings of the virus. A priority should be building solutions that gain similarly widespread public participation yet for the explicit purpose of addressing the groundwater crisis.

Perhaps the most unsettling difference is that while there seem to be favorable odds for a coronavirus vaccine, collective action to address global groundwater depletion is not guaranteed.

Xander Huggins is a Ph.D. student at the University of Victoria and the Global Institute for Water Security

Tom Gleeson is an associate professor in the department of civil engineering at the University of Victoria

Jay Famiglietti is the executive director of the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!