Water-Related Risks Strand $Billions in Energy, Mining, Power Projects

Droughts, floods, and civic opposition cause huge losses.

A stranded asset in the making. The Kusile coal-fired power plant in South Africa is years overdue, billions over budget, and may not have sufficient supplies of water when it is completed in the early 2020s. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

In early November 2002, six years before Lehman Brothers melted down and the American economy came much too close to collapsing, John Cassidy wrote a prophetic article in the New Yorker magazine on ominous trends in U.S. home mortgage financing. Cassidy, one of the top U.S. financial journalists, reported that softening housing prices, easy lending practices, and wage earners taking on more debt than they could possibly afford “could also mark the beginning of something much more serious.”

More than a decade later economists and financial analysts are again identifying powerful signals of economic distress, this time in the energy, mining, power-producing, and farm industries.

Converging economic, ecological, technological, and political trends are causing the turmoil. A good deal of the distress is linked to the Earth’s shifting hydrological conditions caused by climate change.

Economists and financial analysts are again identifying powerful signals of economic distress, this time in the energy, mining, power-producing, and farm industries.

Concerns about rising carbon levels in the atmosphere, and competition from natural gas suppliers and renewable energy, dampen demand for coal. Global prices for coal, oil, and minerals have tumbled to near-record lows in constant dollars. Coal-fired power plants are being cancelled across Asia. The largest coal companies in the United States are in bankruptcy.

Almost $US 400 billion in planned development in Canada’s oil sands region, where water volumes in the Athabasca River are in doubt, have been cancelled, according to an analysis by Wood MacKenzie, a research firm.

Droughts are wrecking grain harvests in Africa and Asia, and drastically reducing hydropower production in South America and Africa. Powerful local opposition campaigns are shutting down construction sites for new dams in Panama and India. Hard rock mineral mines are closing on five continents, many because of civic rebellions fueled by fears of disruptions to local water supplies.

Stranded in the Ground

Taken in aggregate the various signals, like channel buoys frantically bobbing in tempestuous seas, cause bankers and economists to express conflicting views about the severity of the market turmoil and whether the global financial system is sound. For the time being, much of the analysis on the financial losses focuses on the plunge in oil and coal prices, and the potential that a huge portion of the global reserves of oil, gas, and coal will be “stranded’ in the ground to curb climate change.

Robert Kaplan, the president of the Dallas Federal Reserve, said earlier this month that banks will suffer losses on energy loans following the collapse in global oil prices, but they will not pose a broad risk to the economy.

“We watch this issue very carefully and we watch related areas of commercial real estate exposure. There will be losses,” Kaplan said in an interview on CNBC. “I don’t think this will be a systemic issue.”

Concerns about rising carbon levels in the atmosphere, and competition from natural gas suppliers and renewable energy, dampen demand for coal. Global prices have tumbled to near-record lows in constant dollars. Here, coal awaits export in Richards Bay, South Africa. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

But Mark Harrington, an oil industry consultant, asserted on CNBC in January that defaults on debts in the fossil fuel sector could exceed losses sustained in the 2007-2008 market crash.

“Oil and gas companies borrowed heavily when oil prices were soaring above $70 a barrel,” he wrote on CNBC. “But in the past 24 months, they’ve seen their values and cash flows erode ferociously as oil prices plunge—and that’s made it hard for some to pay back that debt. This could lead to a massive credit crunch like the one we saw in 2008. With our economy just getting back on its feet from the global 2008 financial crisis, timing could not be worse.”

The difficulty in gaining a firm understanding of the global risk to world financial markets is due, in no small part, to the sharply accelerating pace of environmental and social change. For much of human history ecological transformation took centuries, and seminal social change took generations. In the 21st century the shift in hydrological cycles is occurring over a decade, and social changes – like the global rebellion over mega industrial projects – develop in just a few years. Global markets respond in weeks in some cases, and overnight in others.

“The economic impact of environmental risks is incredibly large already and is now accelerating. Uncertain physical climate change impacts and volatile societal responses to such impacts will almost certainly increase losses across all sectors of the global economy,” said Ben Caldecott, director of the Sustainable Finance Programme at the University of Oxford, in an email message. “Given that these impacts are large, growing, and systemic, they can have implications for financial stability. We don’t know whether this might happen and from which part of the financial system.”

Schedule Accelerates

The quickened 21st century timetable is undermining methodical planning and construction schedules, and wreaking havoc with investment strategies based on years of firm returns.

Both facets of development sustained the world’s energy, agriculture, mining, and power sectors for nearly all of the 20th century. The 21st century, though, introduced deeper droughts, heavier floods, and more capable rural opposition campaigns. It also delivered an investment community that can move billions between accounts at the speed of light. Like a swarm of bees attacking an intruder, the new conditions are overwhelming an industrial system that takes 10 years to build power plants expected to operate for 50, or develop big farms expected to last a century.

For much of human history ecological transformation took centuries, and seminal social change took generations.

Investors and financial managers scramble to figure out a strategy for keeping afloat. A study by HSBC, a large British bank, found an immense threat to global financial stability from stranding unburned fossil fuels. It joined similar research by Citibank, Standard & Poors, Bloomberg, the Bank of England, Oxford University, and the London School of Economics. The total potential loss in revenues from keeping fuels in the ground would be $US 2 trillion to $US 3 trillion, they concluded.

Water Safety is Huge Risk

No study, though, has yet been conducted on the market consequences or the financial risks caused by droughts, floods, and civic opposition campaigns that are producing actual losses around the world — depleted grain sales, power plant closures and cancellations, reduced equipment sales, and cancelled energy and mining projects. The closest analysis, published last year by the Prudential Regulation Authority, a unit of the Bank of England, found that big losses worldwide caused by what the authors called “natural hazard events” nearly tripled between 1985 and 2015, from 350 to 950 annually. And 480 of those events were related to hydrological disturbances – droughts, floods, and civic campaigns that feared the loss of water supplies or pollution.

That lesson is not lost on major business organizations, the World Economic Forum among them, or the small and growing number of financial investment firms that now classify water security at the top of the list of financial risks to business.

Terra Alpha Investments, a year-old financial firm in Middleburg, Virginia, published a study in March that urged its clients to weigh engagement with water supply, water quality, and water conservation as a telling measure of a company’s capacity to prosper in the 21st century. According to the study, Navigating Rough Waters, companies that did not completely understand their water needs, or embrace plans for quickly adapting to water stresses, were bound not to succeed.

Coal-fired power in Ulan Bator, Mongolia. Much of the analysis on financial losses focuses on the plunge in oil and coal prices, and the potential that a huge portion of the global reserves of oil, gas, and coal will be “stranded’ in the ground to curb climate change. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

The same guidance applies to communities and to nations, said Amy Dine, the firm’s director of advocacy. “Water has been largely a free and amply available resource in many parts of the world with little thought given to pricing it for scarcity, let alone adapting to reduced consumption,” said Dine. “Like stranded oil assets that companies borrowed money against, companies that continue to blithely operate without thinking about water as a constrained resource may find themselves squeezed by lost revenue and botched operations.

“Water is an absolute risk to companies. It’s an absolute risk to economies. It is not being recognized by financial professionals like stranded energy assets are right now. But water-related risks are just as significant. Water affects every single sector.”

Examples in the United States and around the world are legion:

Last year, in Alabama, the Drummond Company withdrew its plan to mine coal south of Birmingham along the Black Warrior River. The new mine, approved by the state, generated a decade of fierce public resistance because runoff and process water discharges would contaminate the river, the source of drinking water for 200,000 residents.

China this week announced it was cancelling or indefinitely delaying construction of 200 coal-fired power plants capable of generating 105,000 megawatts of electricity, or about a tenth of U.S. generating capacity. Carbon emissions, toxic air pollution, and constraints on the country’s freshwater supplies, particularly in the dry northern Yellow River Basin, were among the reasons for the move.

A small and growing number of financial investment firms now classify water security at the top of the list of financial risks to business.

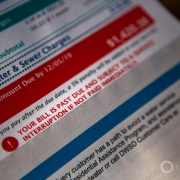

In South Africa, the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power plants are years overdue, tens of billions over budget, and may not have sufficient supplies of water to operate at full capacity if and when they are completed in the early 2020s.

Social conflicts in Peru, principally focused on disruptions to water supplies, have resulted in the indefinite suspension of $US 21.5 billion worth of mining projects since 2010, according to the Peruvian Institute of Economics. The country also lost $US 14.9 billion in anticipated mining export revenue. Earlier this year Newmont Mining cancelled the development of the $US 4.8 billion Conga copper and gold mine. Metal prices are low, and the mine was opposed by Andes farmers because four natural lakes would have been drained and replaced by manmade reservoirs.

Three years ago, Romania ended 14 years of public opposition and cancelled plans by Canada-based Gabriel Resources to build one of Europe’s largest gold mines. Citizens fought the mine’s plan to separate gold from ore with cyanide, a leaching process that has contaminated rivers and groundwater around the world.

Hydropower Stranded Assets

Construction of new hydropower dams has been particularly sensitive to the new ecological and social conditions.

In Honduras this month the three major financiers of the Agua Zarca dam suspended the project. The decisions follow the murders in March of two of the leaders of a grassroots alliance that opposes the dam because of loss of farmland and concerns about water supply and quality.

Public pressure in Brazil forced the government two years ago to postpone the bidding process for constructing the 8,040-megawatt São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric power plant in the north of the country.

Production agriculture, based on single crops and huge water consumption, sustained big financial losses globally from droughts. Here an orange grove in California. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Vietnam recently cancelled plans to build two dams on the Dong Nai River that would damage ecologically valuable and globally unique wetlands.

“Large dams cause a lot of damage. And if you look at the economic details of large dams, they are a stranded asset as soon as they get built,” said Peter Bosshard, the interim executive director of International Rivers, a global advocacy group based in Berkeley, California. “They take a long time and are expensive. Many will never recoup the investment. The vagaries of climate change and drought empty reservoirs for half a year. Floods create more sediments and are a safety hazard.

“Many dams have become an economic burden. It’s something developers are starting to realize. The boom in dam building that existed several years ago has been broken. The number of large hydropower plants coming online is dwindling.”

The trends point very plainly to heightened economic turmoil for companies and nations that pursue conventional mega-industrial energy, mining, and power supply projects.

The trends point very plainly to heightened economic turmoil for companies and nations that pursue conventional mega-industrial energy, mining, and power supply projects that cost billions, take years to build, and consume, pollute, or disrupt water supplies. Revenue losses are tilting financial markets all over the world. How far markets are out of balance is not clear. Analysts, though, are worried, and investors are shifting their wealth to new opportunities.

One of them is renewable energy, principally wind and solar installations. They tend to be much smaller investments and produce less power than big coal-fired and nuclear plants. They also take 24 to 30 months to build. Such plants, more efficient in the planning and finance stage, and more flexible in the construction stage, also consume scant amounts of water. In the last two years private investors have flocked to the industry. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, clean energy investment in 2014 and 2015 totaled almost $US 645 billion. Most of that money was spent developing electricity from the sun and the wind, energy sources that are free of charge.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!