World Economic Forum Ranks Water Crises as Top Long-term Risk

Water is connected to the world’s most severe problems

A lone man watches a hawk fly over Delhi’s crowded skyline, which is topped with thousands of private water tanks that supply the city of 22 million. Corruption, bureaucracy, pollution, scarcity, slow environmental reviews, and inefficient transmission lines are causing ongoing water crises and unstable energy supplies across the country. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

An annual survey of the world’s business, political, and scholarly elite reinforces a message that leaders are beginning to understand with greater depth and clarity: pay attention to water.

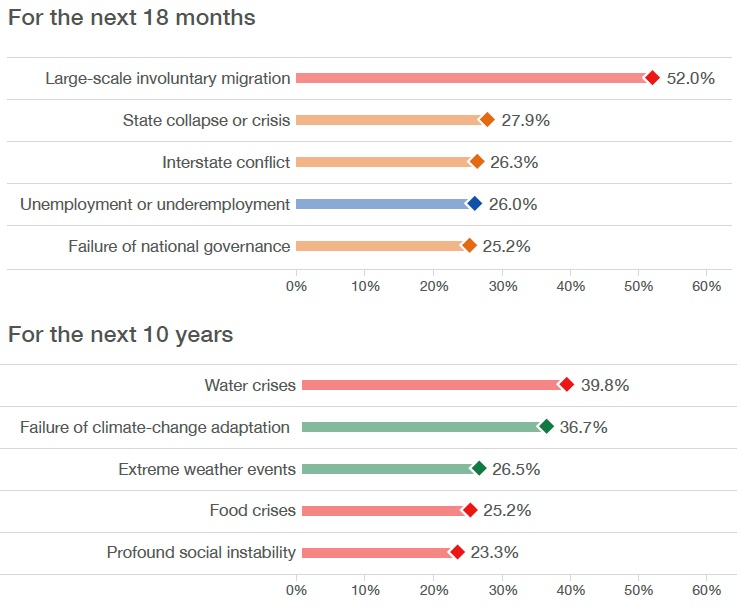

The World Economic Forum, whose membership includes heads of state, CEOs, and civic leaders, ranked water crises as the top global risk to industry and society over the next decade. Last year, water crises earned the top spot as the most damaging short-term risk. Along with water’s rise in the Paris climate talks, the rankings indicate that water, long the purview of engineers and lawyers, is now an urgent political matter.

Water has become a serious social issue.” — Erwann Michel-Kerjan, Wharton Risk Center

The 11th edition of the Global Risks Report, made public this week and viewed as a distillation of the concerns of the world’s most influential businesses and governments, is a warning signal for turbulent times. National economies, some slow to recover from the great recession, are still saddled with debt, unemployment, and slow growth, while facing technological disruptions that promise to upset entire industries. A morass in the Middle East draws countries with superior firepower into conflict with hateful groups whose murderous ideas inspire zealots abroad. The fall in oil prices is forcing petro-kingdoms to reel in fuel and resource subsidies. Most of these trends were noted in previous World Economic Forum assessments. They are now coming to pass.

Amid the economic turbulence, disquieting long-term ecological events also are revealing themselves more fully and destructively. Environmental stress, worsened a by warming planet and a growing population, is leading to tension, both within and between countries, over scarce land, food, and water. The global average temperature is expected in 2016 to be 1 degree Celsius above 1850 levels. A carbon-influenced climate blanket is causing ice sheets to melt, droughts to intensify, and rising seas to flood Miami, Dhaka, and other coastal cities with greater frequency. Ethiopia is at the brink of yet another famine. South Africa, traditionally a corn exporter, will import nearly half its domestic needs this year due to the country’s worst drought in 34 years.

Above all, the devastation of the Syrian civil war, touched off in part by a deep drought, has laid bare the tight weave between geopolitics, international security, migration, climate change, and water. These links will force leaders to adjust to interdependent, cascading consequences, argues Erwann Michel-Kerjan, executive director of the Wharton Risk Center at the University of Pennsylvania, who helped write the report since its inception.

“In the past four to five years, water has increased in importance,” Michel-Kerjan told Circle of Blue. “There’s more stress on the system combined with large unemployment and budget deficits in much of the world. Money that would have gone to address water issues has been spent elsewhere. Water has become a serious social issue.”

Water Is Top Long-term Risk

The goal of the report, a survey of nearly 750 members of the World Economic Forum, is to identify global risks, determine how they are connected, and assess the potential consequences. Global risks are those that affect multiple countries or industries. Only with a common understanding of the problems, the report argues, can collaborative solutions, the most effective means of addressing risks that span borders, can be pursued. For the survey, members are asked to rank 29 risks based on two criteria:

- Impact, which is a measure of severity

- Likelihood, which is the chance of the event occurring within 10 years

Water crises, which ranked first in 2015 for impact, fell to number three this year. They were ranked ninth for likelihood. Water crises, however, were deemed the risk of greatest concern over the next 10 years.

“Many decision makers thought that water problems are only in developing countries,” Michel-Kerjan said. “Now more developed countries are seeing the effects.” He noted the four-year California drought that cost the state an estimated $US 2.7 billion in 2015 and is steering local, state, and even national politics in the United States.

While involuntary migration was deemed the greatest short-term risk, water crises ranked as the top long-term risk. Graphic courtesy of the World Economic Forum.

Climate Connections in a Close-knit World

Water crises, along with migration, infectious disease, and social instability, are categorized in the report as societal risks. These are the core risks, cumulative in nature, that are most connected to other threats. Water was reclassified in last year’s report from an environmental risk to a societal risk, an acknowledgement of water’s reach.

There is no better example than the Syrian civil war, Michel-Kerjan said.

A four-year drought, one of Syria’s worst, began in 2007. Farmers, unable to harvest a crop and seeing food prices spike, moved to the cities to find work. Once there, discontent grew at the Assad government’s ineffective response. By 2011, the stew was cooked, and the conflict began.

Since then, scholars and scientists have determined that climate change was an accomplice in the conflict, worsening the drought that drove as many as 1.5 million from their homes. The damage is now worse. The Syrian conflict has unleashed 4.6 million refugees, with the burden mainly falling on Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and other countries in the Middle East that are struggling to provide food and water to their own people, let alone a mass of refugees in the desert. Za’atari, the largest refugee camp, in Jordan, hosts more than 80,000 people. With a wastewater treatment plant, schools, and hospital, it is fast becoming a city.

Because of the unstanched flow of refugees from conflicts in Afghanistan, Somalia, and the Middle East, the survey respondents ranked involuntary migration as the top risk over the next 18 months. The report, however, notes that the underlying trends of climate change, water crises, and conflict. A special section is devoted to these connections.

Building Resilience

Not all is gloom. While identifying risks, the report also outlines a basic response. Leaders ought to adopt bend-but-do-not-break strategies that allow cities, countries, and districts to face ecological disaster and social upheaval without disastrous results. In other words, build resilience.

A group of homeless men face the morning sun after a night spent in a park in Delhi, India. The United Nations estimates that urban populations will grow by 60 percent by 2050, stressing water, land, waste disposal, and housing. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Though the threats are many, the response need not be conflict and fear. The American West, wracked as it is by drought, nonetheless is a new cauldron of cooperation over water. Seeing falling water levels in Lake Mead, the seven states in the Colorado River Basin are acting to keep more water in the big reservoir. Mexico and the United States signed an agreement to address pollution in the Tijuana River.

The same pragmatism that led Idaho farmers to voluntarily agree to cut groundwater use by more than 10 percent can be applied to other climate-driven problems. Migration, for instance.

Whereas some see threat, Geoff Dabelko, an expert on conflict and natural resources at Ohio University, sees migration as a potential tool for adapting to climate change. Instead of painting migrants as a menace, leaders ought to see the movement of people as an option for responding to the risks of global environmental change that are highlighted in the report.

“The challenge is not to vilify it, but recognize it as a reasonable thing to do,” Dabelko told Circle of Blue.

Dabelko noted that people have migrated in response to environmental changes for millennia. Allowing for greater mobility, both short-term, to take advantage of seasonal work, or long-term, to flee a swamped homeland, could be a response to drought or to rising seas. The political difficulty of such actions would require a deft touch.

“We have to see migration as part of the solution, not just as the problem,” Dabelko said. “It’s not just a threat but an opportunity.”

J. Carl Ganter, Circle of Blue’s director, is a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Water.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton