Q&A: Solomon’s Water

An interview with the author of WATER: The Epic Struggle for Wealth

By Andrea Hart

Circle of Blue

Water weaves through history, giving rise to conflict, collapses and creation in civilizations. In his latest book, WATER: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and Civilization, economic journalist Steven Solomon examines the economic and social relationship between people and water– tying the precious resource’s history to its unstable present. Circle of Blue caught up with Solomon to discuss the book’s central themes, especially what we can learn today from water’s role in our past.

What went into researching the book and linking all of the stories together?

I’ve never really quite stopped researching – but I’d say I spent about six years. For the history sections, I’d try to find several of the major sources, as long as they’re consistent with one another. Then, on the current affairs, there’s an awful lot of published material, I used some books, some reporting, some resource from international organizations, especially the World Bank — we spent hours and hours of time back and forth on the phone. You know, I almost died in the middle of this, I got a bacterial infection that got into my blood system and lodged itself in my back and had some emergency back surgery. That lead to a whole recovery, so exactly how long it took to finish the book is a little vague. I’m 56 years old – I’m not a young man. I’ve been to Egypt and went down the Nile and traveled to Peru in the jungle and mountains, which wasn’t done in research with this book but it does come into the picture as for formulating the book’s worldview.

Why is it that water scarcity seems to be so easily glossed over and hard for people to grasp?

We don’t have an Al Gore for water yet but we need one – water is the only critical natural resource to which we don’t really treat as an economic good. It’s totally emotional, because we are water, we are not oil, we are not iron and we need it every day — in a spiritual sense there’s some affinity we have for it at a visceral level. You can’t live without it so you can’t just treat it as an economic good — you want a human right to water concept as well.

What did you think of the recent McKinsey report that economizes water? You offer a similar solution in your book — how can creating a market system, as you suggest in your book, translate into efficiency in water usage?

Though I haven’t fully read the report, I think that the approach that McKinsey is taking and the analysis that they’re doing is terrific this is what’s got to happen to win support for reform.

My argument in the book, is provided that the market solutions are anchored by an invisible green hand mechanism and you let the market operate freely, while having it anchored in a golden rule — you return the water, in the same condition that you took – and you’ll be able to sustain you sustain the ecosystems.

But how do you come up with solutions when there seems to be a tug of war between developing localized solutions while maintaining global awareness of the crisis?

Many of the water issues have to be dealt with at a localized level. While it’s everybody’s hydrology — the way societies are organized, and the nature of it — water scarcity is largely an organizational issue rather than a technological one.

We now have a global level and local levels for these problems to be dealt with now and in some sense there is a tension because that’s how we’ve done it in the past, and we’ve been able to deal with certain issues. But the truth is that, you do need some kind of a top line best practices, guidelines, or goals that can be agreed on at the global level. This is a whole new level of challenge — you do have to be aware and tackle the water issue at the global level, but each nation takes care of itself, whether it’s bilaterally or regionally. I do think that a lot of this is going to come from the bottom up.

What was the most eye opening experience for you while working on this book?

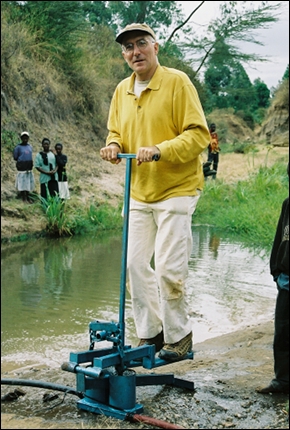

I connected some dots between the problem of water and the changelessness of history over time. I witnessed lives where you’re born and you live maybe 40 to 50 years, and you die and your life is materially no better than when it was when you were born. The Kenya trip was an eye opening experience for me. We were seeing people’s water problems on a daily basis and reinforcing a dam with them — digging in the dirt we had picks and shovels and bags and created an assembly line. You know how back breaking and time consuming it is and yet how much their survival depends on building this dam? That is inconceivable to someone who’s raised in U.S. society where all you have to do is call in a bulldozer to solve the problem. And they were lifting water – which was about 40 to 50 pounds a person in a day, and these are women and children doing it. To be able to project yourself into time and into history was exciting and depressing. The unevenness of history layered is pretty striking, we’re born the same as human beings but we have such different realities.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!