NASA Mission Measures How Ocean Salinity Affects Climate and Water Cycle

Launching in June, the Aquarius satellite mission will improve scientific understanding of the global water cycle.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Salt concentrations in the earth’s oceans exist in a narrow band, usually between 32 and 37 parts per thousand. Within this range, even smaller fluctuations can significantly alter global weather patterns. The salinity difference between an El Niño year and its sibling climatic variation, La Niña, is a single part per thousand.

“Small salinity changes have a large effect on water density,” oceanographer Gary Lagerloef, from Seattle-based Earth and Space Research, told Circle of Blue “These changes can set up density gradients that cause seawater to move and climate patterns to shift.”

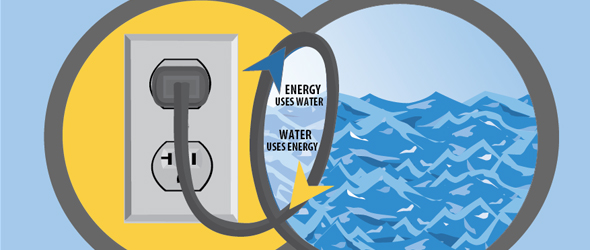

The density of seawater is a function of salinity and temperature, Lagerloef explained. Saltier water is heavier and will sink deeper in the ocean, where it joins currents that circulate water around the globe. These currents—such as the Gulf Stream, from the Florida coast to northern Europe—affect how the ocean transports heat, which, in turn, influences rainfall patterns. Precipitation completes the cycle by altering salinity, both through rainfall over the ocean and continental river flows.

Stable salt densities in the oceans keep the earth’s climate in balance, scientists believe. If the densities were to oscillate irregularly—and some studies have shown a slower circulation pattern in the last half century—the congenial climate known to most of humanity would be thrown out of whack.

Despite the consequential role salinity plays in the global water cycle, scientists have only a faint understanding of how the process works, largely because data collection is limited to an unevenly distributed network of 3,000 buoys.

The Aquarius/SAC-D satellite mission will plug that hole.

Launching June 9 from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base, the mission will feature NASA’s Aquarius satellite, one of eight instruments on board the Argentine-built craft. Lagerloef is the principal investigator for the project, a collaboration between NASA, Argentina’s national space agency, and several European agencies. Aquarius will use long-wave microwaves to measure the salt concentrations on the surface of the ocean.

Scheduled to last at least three years, the mission will produce a comprehensive map of global salinity in its first year. Subsequently, scientists will be able to compare interannual and seasonal variations in salinity and begin to understand their effect on climate patterns such as El Niño.

The satellite will survey the entire globe once every seven days, but maps will be produced every month in order to smooth measurement errors.

Once the surface data is gathered, they will be integrated with information from the buoys, which are able to measure salinity up to a depth of 2,000 meters. This means that the combined output of satellite and buoy data will give a more detailed description of salt concentrations throughout the water column.

The Aquarius data sets will also be added to the data collected by other NASA satellites to analyze how glacial melting, ocean heating, and changes in ocean salinity affect sea level. Climatologists expect to be able to use the data to improve climate forecast models.

The oceans are really the place to look for knowledge about the water cycle, according to Lagerloef. That is where the action is, so to speak—some 86 percent of global evaporation and 78 percent of global precipitation occurs over the world’s oceans.

“There are direct connections between what happens over the ocean and what happens on land,” Lagerloef said. “The ocean is a vast, but poorly understood, part of the water cycle.”

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. Contact Brett Walton

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] کلرید به عنوان فراوان ترین نمک در اقیانوس ها دارای یک تاثیر مستقیم بر آب و هوا. دمای اقیانوس ها را تنظیم می کند و جریان های اقیانوسی […]

[…] the most abundant salt in the ocean, sodium chloride has a direct effect on the climate. It regulates the oceans’ temperature and drives the ocean currents. Consequently, it also has a […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!