Sao Paulo’s Water Waiting Game Avoided Rationing But Produced Huge Risk of Severe Shortage

Desire to protect the poor left Brazil’s driest city few options other than new pipes and prayers for rain.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

In lieu of water rationing, Brazil’s largest city has decided to manage its severe drought by spending millions to tap the deepest pools of its drained reservoirs. The risky move has put leaders of one of the world’s largest water utilities under a global media microscope, and invited harsh criticism from some hydrologists and politicians.

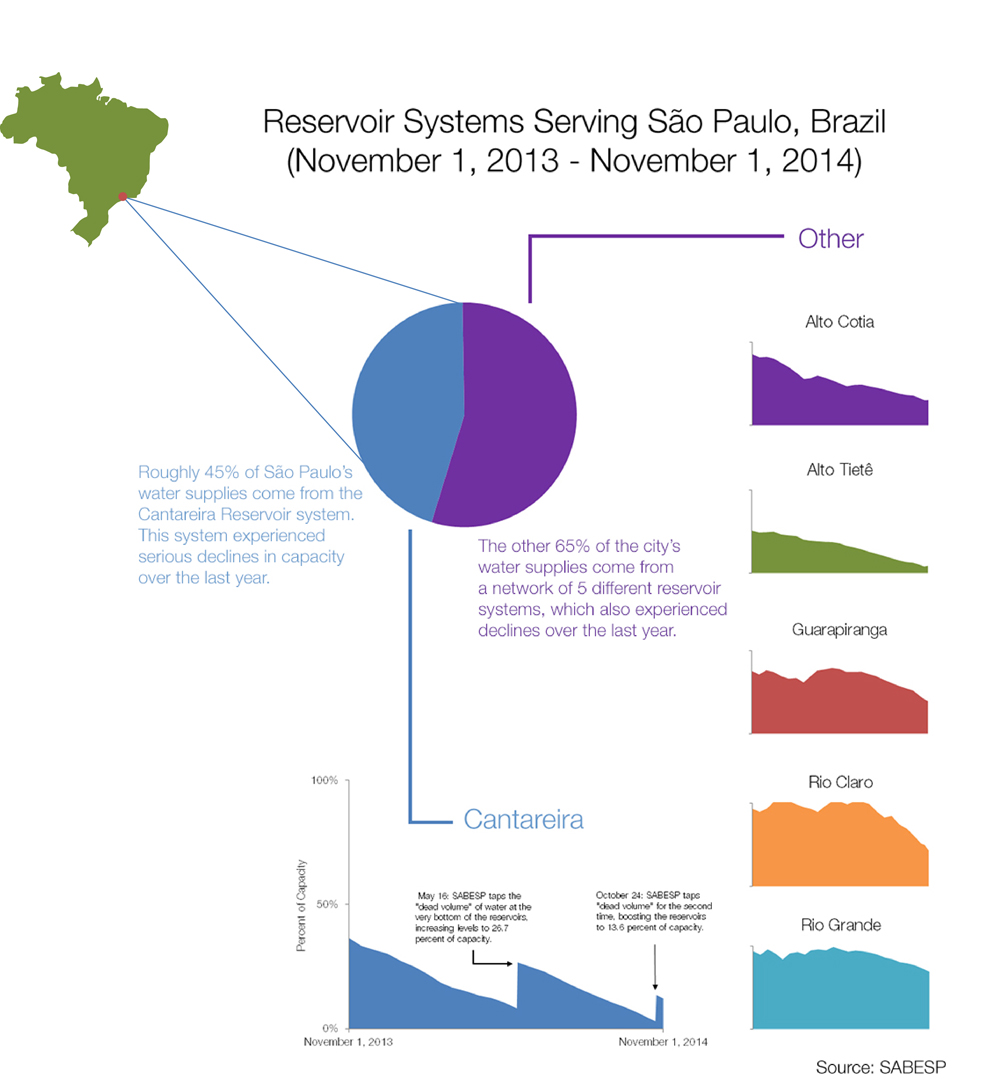

SABESP, Sao Paulo’s water utility that serves 20 million residents, chose to extend its water-intake pipes into the city’s Cantareira reservoir system to tap the water at the very bottom of the reservoirs twice over the last six months. The first extension cost $US 80 million and boosted the reservoir system above 26 percent of its capacity in May. The second extension, completed in October, raised water production to 13 percent of capacity after it had dipped as low as 3 percent.

–Monica Porto, professor

University of Sao Paulo

The utility’s executives contend that their decision to drain the deepest regions of the Cantareira reservoirs will avoid hurting the poorest and most vulnerable groups and will ensure enough water until March 2015. By then, they say, seasonal rains will refill the city’s freshwater reserves — though conservation efforts will still be needed.

But critics call the drought-management strategy irresponsible, dangerous, and politically motivated. The reason is the outsize risk not only to Sao Paulo but also to the rest of the country if the drought continues and the region’s water supply collapses.

“If we are not lucky and we face another severe rainy season, continuing the shortage of rainfall, we will face an even more difficult situation,” said Alceu Guerios Bittencourt, president of the Sao Paulo chapter of the Brazilian Association of Sanitary and Environmental Engineering (ABES-SP). Bittencourt told Circle of Blue that he agrees with the actions taken by the city’s water authorities, but he recognizes the threat of a second dry rainy season. “We don’t know. It’s possible the problems will be more difficult, but that will not only be true for Sao Paulo’s drinking water system — we could have a very serious problem in our energy system and transportation and agriculture. That would mean a much more problematic situation as a whole in the country.”

Sao Paulo’s water managers and the city’s residents, in effect, are embroiled in a high-stakes challenge to delay or entirely evade the most calamitous threat, namely running out of water. The outcome is being widely watched by dry cities around the world – from Los Angeles to Beijing, from Doha to Melbourne – which seek lessons in managing water supplies in an era of hydrological disruption and diminishing moisture.

The central concern in Brazil, of course, is whether SABESP’s investment in new pipes and conservation incentives – and not in a rationing plan – will work.

“It is very difficult to wait,” said Monica Porto, a professor of environmental engineering at the University of Sao Paulo and an expert on the city’s water supply, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “Everyone is afraid and everyone is worried, but there is not much that can be done.”

Drought, Population Test City’s Water System

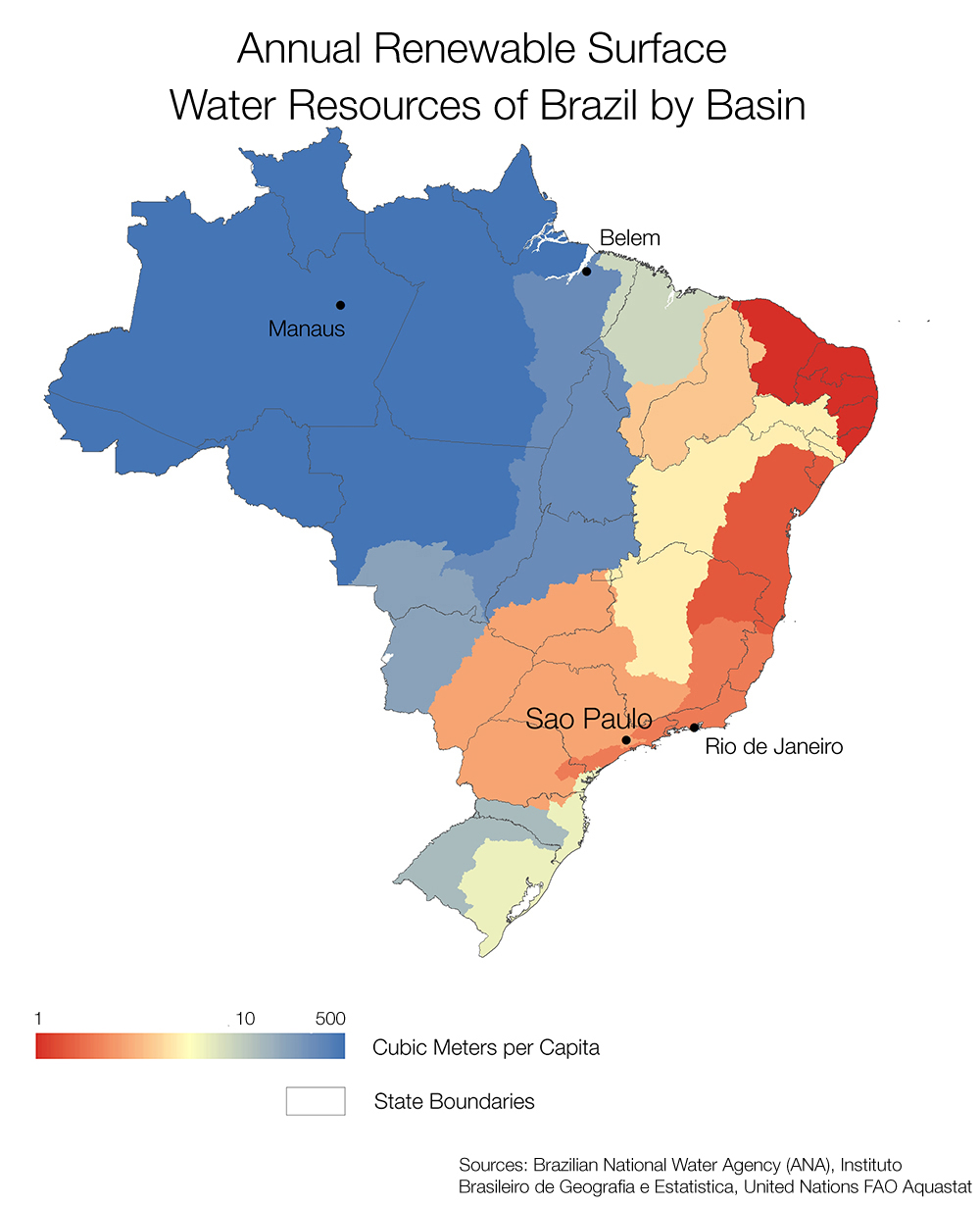

Situated in a nation that typically enjoys one of the most abundant freshwater supplies on Earth, Sao Paulo has quickly become desperately dry. The drinking water system that supplies half of Sao Paulo’s growing population is now 12 percent full after nearly a year of record-setting drought and could have less than 100 days of water in reserve.

NASA satellite images show the shriveled Cantareira reservoirs, which dipped to 3 percent capacity on October 23, as shallow and green, ringed by expanses of brown lake bottom. Aside from drinking and bathing, the drought has other far-reaching effects — hydropower reservoirs, which supply more than 75 percent of Brazil’s electricity, are running critically low in the country’s southeast region, and this could prompt energy rationing next year, according to Bloomberg News. Global soybean prices rose 12 percent in October based on speculation that the summer harvest in Brazil, the world’s second-largest soybean exporter, will be hit by the drought.

Sao Paulo’s plight has two causes. The first is a 13-month drought, the deepest in 80 years. The second is an urban water system that was designed for a nation of water abundance. Despite having one of the largest water-supply systems in the world, Sao Paulo’s enormous population leaves the city with very little buffer to accommodate shocks of this magnitude.

“When the system was designed, the main criteria for the situation was to look at the driest period of the record and to design the system to perform well if the worst drought on the record would repeat,” Porto said. “And what we are seeing right now is that this criteria is not sufficient when we have 20 million people to supply.”

As climate change, deforestation of key watersheds, and population growth put even more stress on the system, engineers and water managers will need to reassess the way that the city supplies and uses its water, according to experts like Porto. Sao Paulo is not alone. Even without taking climate change into account, 45 percent of cities that rely on rivers and reservoirs for their water will be vulnerable to shortages and scarcity by 2040 due to increased agricultural and urban demands, according to a study of 71 global cities published by Stanford University researchers in October.

High Stakes Decision

Rainfall totals in Sao Paulo this year are approximately half of what they normally are by November, according to Brazil’s Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies. The region, which receives nearly 80 percent of its annual rainfall between January and March, is entering its summer rainy season.

–Alceu Guerios Bittencourt, president

ABES-SP

Still, even an average rainy season will not solve Sao Paulo’s water problems completely.

“This rainy season will not be sufficient to recover the reservoirs,” Porto said. ”So if the season is drier than the usual, if it rains less than the average, next year we will be in very bad shape, even worse than today.”

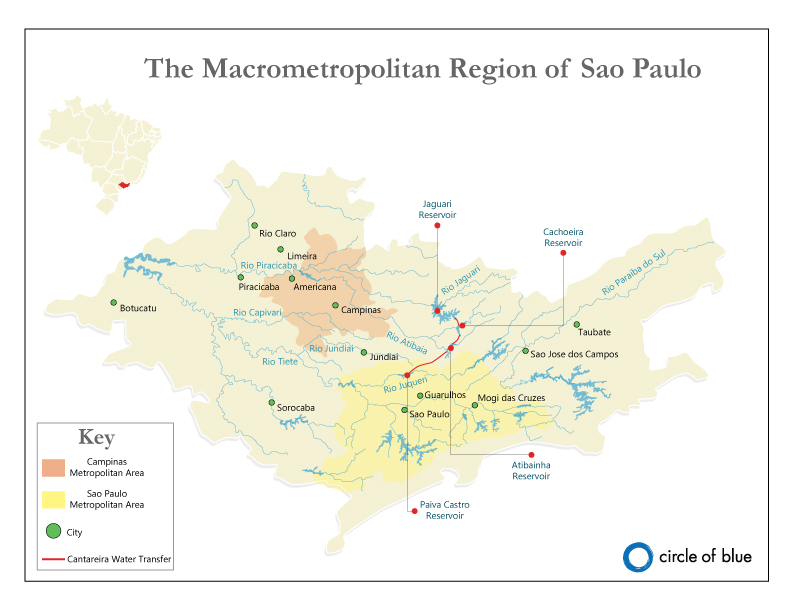

Rationing in the city, however, is both technically difficult and socially harmful, she added. It would require many different steps to physically turn off pipelines and stop and start water across Sao Paulo’s vast distribution system, which delivers water from 28 water treatment plants to a metropolitan region that stretches across more than 2,000 square kilometers (772 square miles) — twice the area of New York City. Furthermore, the poorest neighborhoods are located on the outskirts of the city, meaning these areas would lose water first and regain it last if the system were shut down, according to Porto.

“In an area of this size with so many people, to cut the supply and really turn off the pipelines is the last, last, last measure to be taken because the impact — and mostly on poor people — will be very severe,” Porto said. “I don’t say that this is a measure that will not be taken; it depends on the behavior of the rainfall in the summer. If it does not rain the average [amount], then this last measure will have to be taken.”

In the meantime, SABESP has taken a number of measures to preserve water supply and reduce water use, according to Bittencourt. For example, the utility has supplemented the Cantareira reservoir system with water from other systems that have more reserves, given bonuses to customers who reduce their water use, and reduced the network pressure to reduce water losses at night.

“These measures had an effect equivalent to a rationing operation with a much lower nuisance level to the population,” Bittencourt wrote in an e-mail to Circle of Blue.

Little Help From Outside

In the short term, there is little help available to Sao Paulo from other states or the federal government. Cities like Rio de Janeiro are too far away to share water supplies, and Sao Paulo already got tangled in a legal dispute with Rio in August. It was deemed that Sao Paulo violated national water and energy plans when it tried to withhold water that feeds into the Paraiba do Sul River Basin. The Paraiba do Sul is used to supply Rio with drinking water and hydropower. Sao Paulo later released the correct amount of water downstream following an order from Brazil’s National Electric System Operator (ONS).

To ensure long-term water supplies, Sao Paulo is relying on two pipeline projects, including one that would take water from the Paraiba do Sul, to augment the city’s supply. The Paraiba do Sul project would siphon 5 cubic meters (1,320 gallons) of water per second from the river into Sao Paulo’s Atibainha Reservoir, part of the Cantareira system. It requires approval from the National Water Agency because the Paraiaba do Sul is shared by three states — Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and Sao Paulo — and would cost more than $US 200 million, according to local media reports. Construction has already started on another pipeline system that will bring an additional 5 cubic meters (1,320 gallons) of water per second from the São Lourenço River Basin, southeast of Sao Paulo, at a cost of nearly $US 900 million.

The São Lourenço pipeline system is expected to be fully operational in 2018, and the Paraiba do Sul pipeline — if approved — will take at least 15 months to complete. Both will help Sao Paulo create a larger buffer between water supply and demand. Currently, the city demands an average of 69 cubic meters (18,230 gallons) of water per second and has the capacity to supply 70.34 cubic meters (18,580 gallons) of water per second, according to Sao Paulo’s Master Plan for Water Resources. By 2035, demand could surpass 82 cubic meters (21,660 gallons) per second, making both demand management and new water-supply sources necessary, the plan says.

Changing the Status Quo for Water in Megacities

Taking into account climate change, deforestation, population growth, and the inevitability of another severe drought, Sao Paulo will need to change the way that it thinks about water, according to the University of Sao Paulo’s Monica Porto.

“I think that we have an excellent opportunity for turning lemons into lemonade,” she told Circle of Blue. “We have to learn that when you have an agglomeration of urban areas of this size — 20 million people — we as engineers must revise completely the design criteria for those systems. It’s a lesson for us that we will need different design criteria for these types of projects that are so important for the health of the population and for businesses.”

Technology that reduces water use and improves efficiency will be especially important, she said, adding that the changes will require more investment.

“The least-cost criteria is probably the criteria that does not give much protection for the system,” Porto said. “We will have to recognize that to improve the security of the systems will cost more. For people living in these situations, in huge urban agglomerates, water will be more expensive.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

city of Winnipeg mb Canada offered to buy with a tax credit, new toilets for your home that were efficient, this would help sao Paulo with out dated homes and update needed infrastructure at the same time!