In Flint Water Probe, Five Officials Face Involuntary Manslaughter Charge

Criminal investigation touches off dispute at top level of state government.

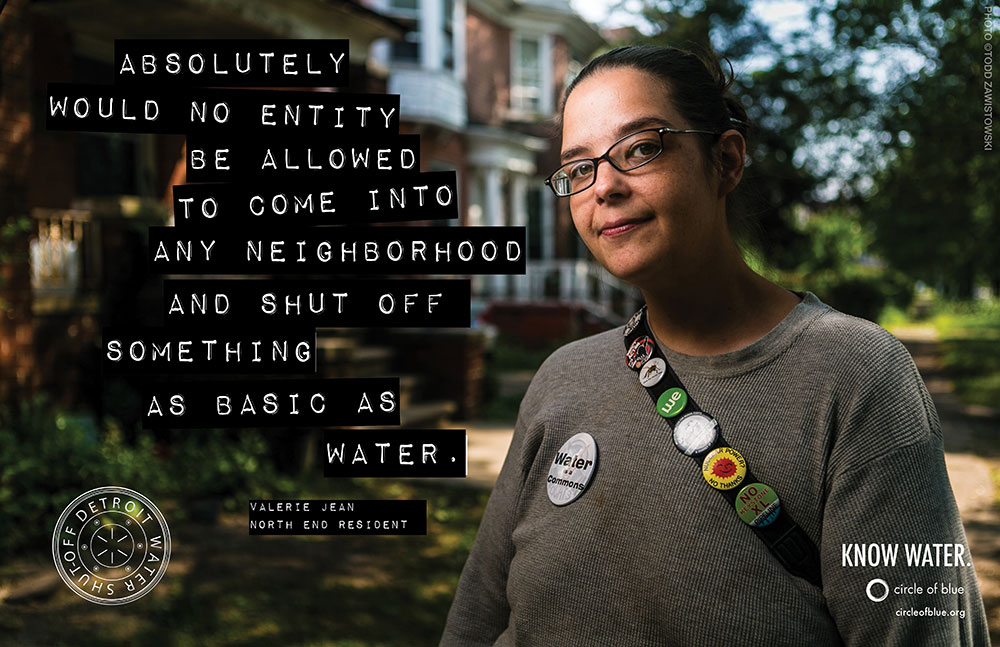

Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette has filed criminal charges against 15 local and state officials and water system operators in his office’s investigation of the Flint water scandal. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Update: In October 2017, prosecutors charged a sixth public official for involuntary manslaughter.

The state of Michigan’s wide-ranging criminal investigation of the Flint water crisis reached the top levels of state government after Attorney General Bill Schuette filed involuntary manslaughter charges on June 14 against Nick Lyon, the director of the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, and four other state and local officials.

The five officials were charged with failing to notify the public or take action about an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in 2014-15 that killed at least one person who received Flint water. The city’s water crisis is most commonly associated with an increase in lead levels but it also coincided with a deadly Legionnaires’ outbreak. The disease is a form of pneumonia, most harmful to the elderly and those with weak immune systems, that grows in plumbing and is spread through airborne water droplets.

“Charging public officials with involuntary manslaughter is unprecedented but warranted based on the evidence and the disgusting disrespect for the law and life,” Noah Hall, special assistant attorney general, told Circle of Blue.

Governor Rick Snyder, though, pushed back against the attorney general’s action, issuing a statement of support for a ranking member of his cabinet, and for Eden V. Wells, the chief medical executive for the department, who was charged with obstruction of justice and lying to a peace officer. “Director Lyon and Dr. Wells have been and continue to be instrumental in Flint’s recovery,” Snyder said. “They have my full faith and confidence, and will remain on duty at DHHS.”

The charges mark a turning point in the 17-month investigation, according to an interim report from the attorney general and special counsel. The state now looks to focus on prosecution of the 15 current and former state and local officials charged with crimes. But Hall did not rule out additional charges.

“We are confident that the courts will uphold the charges we have filed,” the counsel’s report states.

The involuntary manslaughter charges stem from the death of Robert Skidmore, a resident of Genesee Township, who died December 13, 2015, at McLaren Flint Hospital. Skidmore, 85, had contracted the Legionella bacteria six months earlier.

In addition to Lyon, the other officials charged with involuntary manslaughter include:

- Darnell Earley, former Flint emergency manager

- Howard Croft, former Flint Water Department manager

- Liane Shekter-Smith, drinking water chief at the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality

- Stephen Busch, water supervisor at the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality

Involuntary manslaughter carries a maximum sentence of 15 years in prison or $US 7,500 fine, or both. Schuette also filed a lesser charge against Lyon — misconduct in office — that carries up to five years in prison. The four other officials charged on Wednesday already face an assortment of felony charges related to the water contamination investigation.

Wells, the chief medical executive, allegedly lied to a special agent and threatened to withhold funding for a Flint community health partnership if it did not halt its investigation of the Legionnaires’ outbreak. The felony charge carries a maximum sentence of five years in prison or a $US 10,000 fine.

Wells also faces a misdemeanor of lying to a peace officer about her knowledge of the Legionnaires’ outbreak, a charge that could result in two years in prison, a $US 5,000 fine, or both.

Constructing the Timeline of ‘Who Knew What and When?’

Flint officials, under the supervision of a state-appointed emergency manager, switched the city’s drinking water source on April 25, 2014. Instead of pre-treated water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, the city began to withdraw water from the Flint River for treatment at their own plant while they awaited completion of a pipeline to Lake Huron.

The officials said they made the switch to save money in a city with long-standing and deep fiscal deficits. Another effort to save money involved withholding a corrosion-preventing chemical following the switch. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, in contradiction of federal policy, determined that the addition of phosphate chemicals to balance the water chemistry and prevent Flint’s pipes from corroding was not necessary. About a month after the switch, residents began to complain about the water’s odor, color, and skin rashes.

By October 2014, Genesee County, where Flint is located, had recorded 30 cases of Legionnaires’ disease in six months. In the past, Genesee County had seen between two and nine cases per year.

According to the attorney general’s report, on January 28, 2015 the state epidemiologist notified Lyon, of the increase in Legionnaires’ cases in Genesee County. The public was not notified, the report asserts, until nearly a year later. On January 13, 2016, Gov. Snyder declared a state of emergency in Flint. Lyon testified before a state select committee that he first knew of the health problems in Flint from a July 22, 2015 email from the governor’s chief of staff.

Flint reconnected to the Detroit water system on October 16, 2015, a year and a half after the switch.

Cause of Legionella Outbreak Still Uncertain

Michele Swanson, a University of Michigan Medical School microbiologist, who is studying the Legionella outbreak in Flint, says that based on testing of water from Flint homes, hospitals, and control samples, the connection between Flint’s water and the Legionella outbreak is, in some ways, inconclusive.

“From my data I can’t say that the Flint water created a more virulent strain than the control,” Swanson told Circle of Blue. Swanson presented her research at the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) meeting in New Orleans on June 4.

That does not mean no link exists. A stronger, more virulent bacteria is only one way of increasing the risk of infection. Flint’s water after the switch from Detroit’s system could also have allowed the growth of more individual bacteria. Inadequate chlorination could also have fostered bacteria growth.

“The question is how much the outbreak can be attributed to the water and how much to McLaren [hospital],” Swanson said. “There isn’t a clear answer.” She said that Flint had a total of 87 Legionnaires’ cases in 2014-15.

In the coming months Swanson and her colleagues will be testing whether the Flint water chemistry before, during, and after the switch contributed to Legionella growth and resilience.

A witness for the prosecution, however, has a much more definitive answer. Janet Stout, president of Special Pathogens Laboratory and a Legionella researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, will “testify that Flint’s source water change and the subsequent management of the municipal water system caused conditions to develop within the municipal water distribution system that promoted Legionella growth and dispersion, amplification, and the significant increase in cases of Legionnaires’ disease in Genesee County in 2014 and 2015,” according to the investigator’s report.

Stout did not immediately return a phone call and an email message.

In Lyon’s case, the link may not matter, Hall said. The key point for the health department leader, Hall argued, is that he was aware of the outbreak and its expected effects but failed to act as the law required.

Criminal Charges Are Rare

Criminal charges against public officials in response to water system negligence and disease outbreaks are rare. The operator of two New Jersey water systems was sentenced to three years in jail in February 2016 after submitting false water quality data to the state Department of Environmental Protection. The former supervisor of an Oklahoma wastewater plant was sentenced to six months of home arrest and five years of probation in September 2009 for falsifying water quality reports. After an E. coli outbreak in Walkerton, Ontario, in May 2000 that sickened 2,300 people and killed seven, the director of the town’s water utility was sentenced to a year in prison for negligent operation of the system.

No criminal charges were filed in the largest disease outbreak in the United States that was linked to a failed public water system — the 1993 cryptosporidium epidemic in Milwaukee that led to more than 400,000 cases of diarrhea and at least 69 deaths.

Hall said that the public health disaster that occurred in Flint is not a case of inept bureaucrats being asleep at the wheel. After hours and hours of reading emails used as evidence in the investigation, Hall became convinced that the regulators actively disregarded their legal duty. He compared the behavior of the state and local officials to drivers who look at the 55-mile-per-hour speed limit as a guideline rather than a standard of safety.

“They forgot that these laws are there to protect people from being poisoned,” said Hall, who is also a law professor at Wayne State University.

The Michigan legal team investigating Flint is led by Todd Flood and Andrew Arena, both appointed by the attorney general. Flood, the special counsel, is a former Wayne County assistant prosecutor. Arena, the chief investigator, is a former agent in the FBI’s Detroit office.

Court hearings have been held for two of the 15 people charged in the investigation. Corinne Miller, former director of the state Bureau of Epidemiology, and Michael Glasgow, who was the Flint water quality supervisor, both pled no contest to charges of willful neglect of duty. As part of their plea bargains, both are cooperating with the investigation.

“Already with the charges, I hope that we have sent a clear message to environmental and public health regulators that if they do not uphold the law when it is their duty to do so, they will face much more severe consequences than an agency review,” Hall said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton