Report: Updated Laws and Collaboration Needed to Control Legionnaires’ Disease, America’s Deadliest Waterborne Illness

National Academies report identifies deficiencies in plumbing and building codes, policies, and research.

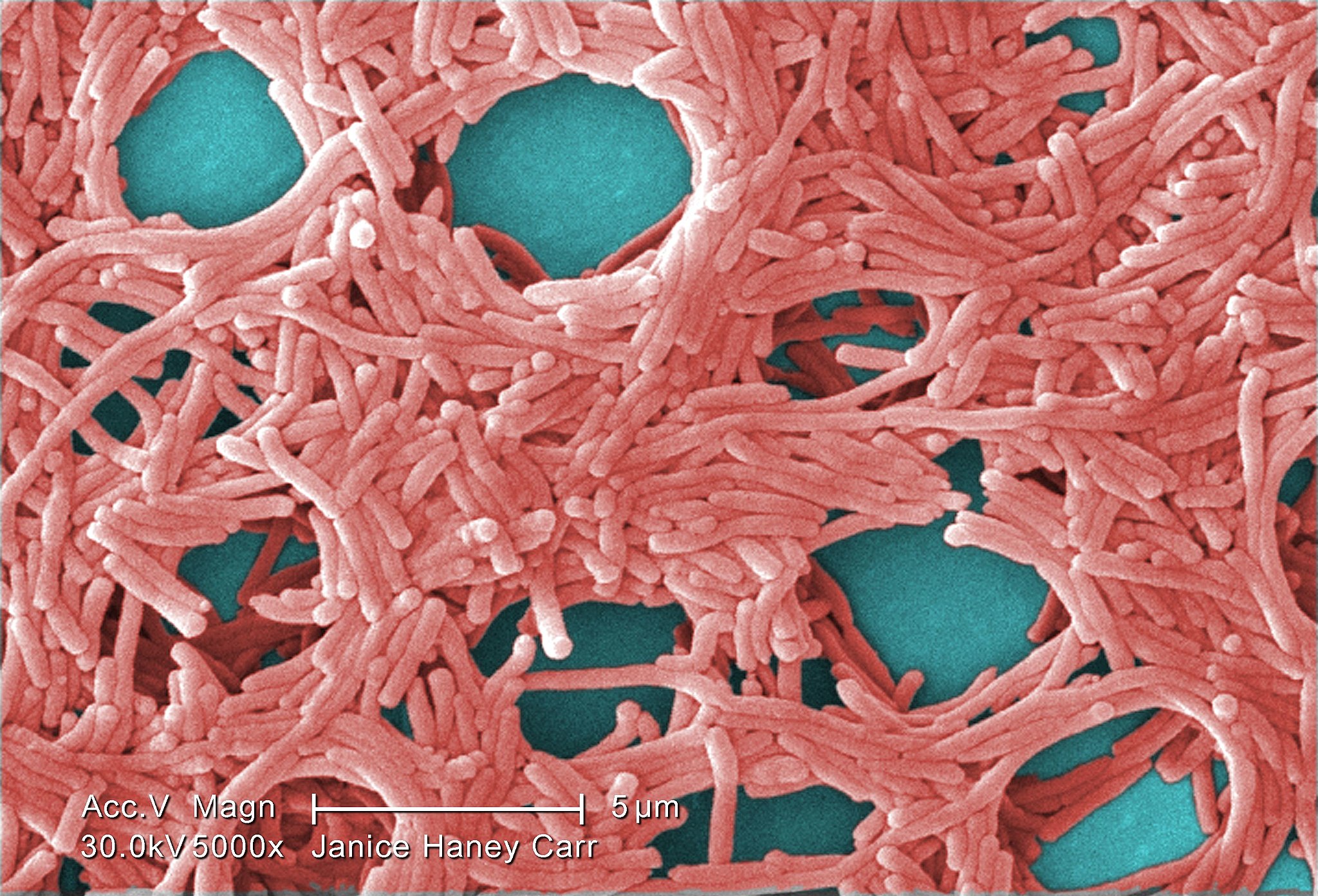

An electron microscope photo of Legionella pneumophila bacteria, the species that causes most Legionnaires’ disease cases. Photo via Wikimedia Commons and Janice Haney Carr/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

A collection of top infectious disease experts, microbiologists, engineers, and health officials warns that federal, state, and local laws, including the benchmark Safe Drinking Water Act, are inadequate for halting the spread of Legionella, the bacteria that are responsible for more deaths in the United States than any other water contaminant.

Convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the 13-member committee’s report on managing Legionella in water systems provides the most comprehensive picture to date of the science of Legionnaires’ disease and obstacles to its control.

We need our public policy to be in line with practices that we know control Legionella.” — Amy Pruden, Virginia Tech

Preventing future outbreaks and individual cases of the pneumonia-like illness that kills nearly one in 10 people it infects requires better coordination between local, state, and federal agencies and building owners as well as stronger policies and scientific studies, according to Joan Rose, the committee chair.

“It will be all of our responsibility to move forward with a national approach to decrease Legionnaires’ disease, and in particular, protect our sensitive populations in the future,” said Rose, a Michigan State University professor who has gained international recognition for her research on microbiology, water quality, and public health.

The report’s release on August 14 came a day before the Sheraton Atlanta Hotel reopened after the largest Legionnaires’ outbreak in Georgia history. The hotel had closed for a month following one death linked to the disease and potentially 79 or more people infected.

The committee offered dozens of recommendations for understanding the rise of Legionella as the country’s foremost acute drinking water contaminant and inhibiting its growth in water systems. The recommendations include: expanded monitoring of cooling towers, which are implicated in numerous disease outbreaks, wider adoption of water management plans within buildings, updating plumbing codes to minimize bacteria growth within water systems, and clarifying regulatory grey zones in the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Disease on the Rise

Legionnaires’ disease, contracted by inhaling contaminated water droplets, was discovered four decades ago following an outbreak at Philadelphia’s Bellevue Stratford Hotel during an American Legion convention. Since then, the number of cases has grown rapidly, especially in the last 20 years.

Reported cases of Legionnaires’ disease have increased five-fold since 2000, but that number is widely assumed to be an underestimate. The committee, extrapolating from data on pneumonia, a related illness, reckons that between 52,000 and 70,000 cases occur in the United States annually, some 10 times higher than the reported rate. More than nine in 10 are individual illnesses, not connected to an outbreak. All those cases add up. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated in a 2012 paper that the hospitalization cost for Legionnaires’ disease was $433 million a year. That figure has surely grown.

Why the increase in cases? Experts cite a number of factors, some or all of which may play a role in the spread of a disease that proliferates at the intersection of the built and natural environments. Water distribution pipes and plumbing systems are aging, which could allow bacteria to flourish in corroded nooks and crannies. The U.S. population is aging as well, and people above age 65 and those with weaker immune systems are more susceptible to the disease. A warming climate may provide an environmental foothold. Water and energy conservation measures result in less water flowing through pipes and cooler water temperatures, both of which can spur Legionella growth. Better diagnostic tests and more attentive doctors could also explain some of the rise.

Given these headwinds, laws, policies, and practices need a makeover, according to the report. Policy gaps begin at the federal level.

“The Safe Drinking Water Act does not provide protection from Legionella,” Rose said at a press conference to release the report.

The landmark law focuses on water as it exits a utility treatment plant. Water quality within buildings and inside homes is, with a few exceptions such as lead and copper, outside the law’s domain. That is a problem because Legionella is incubated inside building pipes, plumbing, and cooling systems. Utilities are required to disinfect water, but those levels diminish over time and distance. A building owner could add supplemental disinfection, to boost the levels from the treatment plant. But doing so could open the building owner to regulation as a public drinking water system, inviting an avalanche of extra paperwork, monitoring, and testing that is, in most cases, prohibitively expensive.

Amy Pruden, a committee member and a Virginia Tech professor who studies microbes in plumbing systems, said that it would be “wonderful” if Congress could provide clearer direction for water systems within buildings. “We need our public policy to be in line with practices that we know control Legionella,” Pruden said.

There are no federal standards for Legionella in drinking water. By looking at a handful of international studies of Legionella outbreaks, the committee determined what appears to be a point at which bacteria concentrations are high enough to trigger widespread infection. That threshold is roughly 50,000 colony forming units per liter of water.

That concentration, Rose said, is an “alarm bell level” at which an outbreak is likely and immediate action by the building owner should occur. Lower thresholds could be used for routine monitoring, she said.

When asked by Circle of Blue about disinfection within buildings, an EPA spokesperson said that the agency is reviewing the study and will use it to inform its efforts to control Legionella.

“EPA will continue to review the study as we work to identify additional steps the agency may take to further improve public health protection against Legionella in regulated public water utilities,” Angela Hackel wrote in an email.

“Everybody Has a Role”

The burden of response is not only on the federal government, Pruden said. Laboratories, federal agencies, researchers, insurance companies, building designers, water utilities, local agencies also need to be involved.

“Everybody has a role to play here,” she said.

Other recommendations in the report range from scientific assessment of the bacteria to actions that building owners should take. Some of those recommendations:

- Register and monitor cooling towers. Cooling towers are a fertile breeding ground for Legionella bacteria and were the cause of an outbreak in the Bronx in 2015 that killed 12 people. The outbreak this summer at the Sheraton Atlanta Hotel was also traced to cooling towers. From the limited evidence available, registration and monitoring succeed in reducing bacteria concentrations. Quebec and Garland, a Texas suburb, are two jurisdictions that instituted such controls and saw improvements.

- Calibrate conditions in building plumbing. Water heater temperatures should be kept above 140 degrees Fahrenheit (60 degrees Celsius) and delivered to the faucet at 131 Fahrenheit (55 Celsius), the committee recommended. The tradeoff is a risk of scalding at higher faucet temperatures, said Michèle Prévost, a committee member. But that can reduced with valves that mix cold water.The committee also suggested that low-flow fixtures should be banned in hospitals and nursing homes. Water conservation increases the time that water sits in pipes, which can raise the risk of Legionella growth because levels of chlorine and other disinfectants diminish. Elderly people and those who are already sick have a higher risk of infection. Green buildings, because they are water- and energy-efficient, also introduced a greater risk of Legionella growth.

- Require public buildings to have water management plans. Hospitals and nursing homes that receive Medicare funding are already required to have water management plans. The committee recommended extending those provisions to all public buildings: schools, hotels, government offices.

- Invest in research, monitoring, and education. Scientists have identified more than 61 Legionella species, but nearly all scientific study focuses on a single branch. The committee recommended more assessment of how the bacteria behave and grow in built and natural environments. They also recommended better diagnostic tools and federally funded centers for research, education, and training, modeled after a program for food safety.

The committee briefed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Veterans Affairs, and EPA, the three federal agencies that funded the report along with the Sloan Foundation.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

My husband died of legionnaires disease within 10 days in 2023. No doctor in the intensive care unit or the 6 doctors who attended him, even thought of legionnaires. Thry missed the diagnosis completely. Meaning, hospitals are not testing for this pneumonia. Patient presents with pneumonia and they don’t even investigate for legionella. That’s a huge problem right there. Doctors need to be alerted to this bacteria. It is a quick killer. It destroys the kidneys in a matter of days.

Sorry for your loss! May I ask approximate location? Trying to see how close to central valley in ca. It’s heading. I seen post for Las Vegas?