Mine Cleanup Law Weakened By Coal’s Decline

Coal mine reclamation has become a flashpoint in the partisan divide over fossil fuel use.

Dalton Branch Mine, VA. Photo © Appalachian Voices / Erin Savage, 2015

By Laura Gersony, Circle of Blue — October 6, 2022

Part two of Circle of Blue’s series on abandoned coal mines. Read part one here.

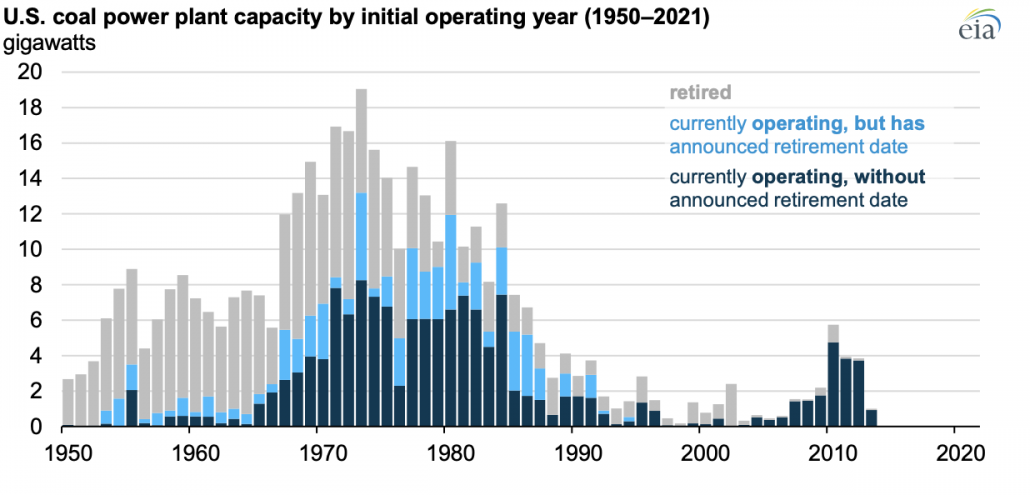

In the late 1970s, a golden age for American coal, skyrocketing oil prices coupled with rising demand for electricity set off a boom in coal-fired power plants. The New York Times declared that the industry hung up a giant “Help Wanted” sign. Coal production was set to roughly double over the next 20 years.

So in August of 1977, when the nation’s coal mine cleanup law went into effect, it reflected the market’s optimism. The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act allowed the states to hold a bond to pay for cleanups if the mining company couldn’t. Lawmakers figured that bankruptcies would be few and far between. To enforce cleanup, the law allowed states to revoke mining permits, a prized commodity.

Forty-five years later, coal is in free fall. Here in the Illinois basin — which straddles the Ohio River in parts of Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky — one-third of the region’s coal is sold to power plants set to retire in the next decade. Every few weeks, another mine is idled or shut down. The threat of revoking permits no longer holds the force it once did.

The mine cleanup law, however, no longer reflects current conditions. It is still built for the industry’s roaring ‘70s. The issue boils down to the fact that the government is not collecting enough money to pay for cleanup.

“The system can absorb the occasional bankruptcy. But it can’t absorb the wholesale decline of the coal industry,” says Peter Morgan, an attorney with the Sierra Club. “The cracks are really starting to show.”

Under SMCRA, states are required to guarantee environmental cleanup even if the company abandons its mine. They do this through a bonding mechanism: the state holds a few thousand dollars per acre hostage until the mining operator has reclaimed the land. If the operator fails to perform adequate cleanup, state regulators confiscate the bond and use it to hire contractors to finish the job.

In the eastern U.S., mine sites left unreclaimed by bankrupt coal companies have already racked up hundreds of violations for harms to the environment and waterways. Policy experts say that the mass abandonment of mines could soon spread to the Midwest — to disastrous consequences for water resources and the environment.

Mine cleanup law was penned during the ’70s, when surging oil prices caused a boom in coal-fired power plants. Photo © U.S. Energy Information Administration

The system of reclamation bonding works, so long as the bond amount is roughly equal to the cost of reclamation. In the Midwest’s largest coal basin, that’s not the case. Illinois keeps about $8,000 per acre in bonding, according to 2018 data published by Climate Home News, and Indiana and Kentucky had only about $4,000 per acre.

The actual cost of reclamation is far greater. According to oversight documents, during 2021 Illinois’ Department of Natural Resources spent an average of $17,000 per acre cleaning up sites abandoned prior to 1977.

As of 2021, Kentucky had about $888 million on hand for cleanup — while estimates of the actual cost of cleanup reach into the billions of dollars. The age of the mine affects the cost of reclamation, as can the region or particular characteristics of the mine site. Across Eastern states collected bonds amount to between 25 percent and 65 percent of the actual reclamation cost. In other words, states have a fraction of the funding necessary to clean up coal’s aftermath.

At the moment, some of those costs are falling indirectly onto taxpayers, as environmental obligations are unloaded during bankruptcy restructuring. Between 2012 and 2017, four major companies — including Peabody energy, the world’s largest coal company, which produces 20 percent of the coal in Illinois — shed more than $5 billion owed for environmental cleanup, and health care for retired workers.

“Whether you know it or not, you’re paying for healthcare benefits that have been dumped on [federal mining agencies] by the bankruptcy code,” Joe Pizarchik, former head of the federal Office and Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, told Circle of Blue.

In other cases, these costs are not being paid at all. The deficit translates into acute environmental harm. This has begun to play out in Appalachia, where coal production has fallen the fastest. Mines abandoned by bankrupt companies have increased sediments or heavy metals in air and water, lowered the water table in some areas, and made the region more vulnerable to landslides, like the one that devastated eastern Kentucky earlier this year.

Recent internal communications obtained by InsideClimate News show that Kentucky regulators are scrambling to deal with unresolved environmental violations at abandoned mine sites. More than half of those violations are located at sites operated by companies that have gone bankrupt.

“This is completely out of control,” wrote one Kentucky Department of Natural Resources official in an email to another earlier this year. “There are a lot of variables, including the massive decline in coal production. But what we are doing right now is not addressing the problems. Something has to give/change before we have a major problem on our hands.”

Coal mine cleanup law is still built for the industry’s roaring ’70s. Photo © Illinois Department of Natural Resources

A Political Quagmire

As challenges across coal country are revealed, states aren’t solving this problem on their own. In Pizarchik’s experience working for the federal mining office, coal-friendly political pressure is a headwind facing state actors trying to strengthen the programs. Likewise, underfunded and understaffed regulatory programs are sensitive to political pressures within state legislatures, which provide half of the operating budget in most states.

“There might be state politics that are prohibiting the regulators from fixing broken parts of the program. That could be a governor; a secretary; some other appointee who doesn’t want it fixed, if it could cost the industry more money,” Pizarcihk said.

The free market isn’t going to solve the problem either. A 2019 report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis projected that “most of the Illinois Basin coal industry will be gone” by the middle of this century. Market analysts say that even the Russo-Ukrainian War, which has temporarily supercharged coal, won’t allow the industry to stave off long term pressures.

Instead, advocates say, mandates to fix broken state programs must come from above. And for the first time in the 50-year history of legislated mine cleanup, these reforms are active in Congress.

The Renew Our Abandoned Mine Lands Act, introduced in June by Rep. Conor Lamb of Pennsylvania, takes a stab at the problem. The RENEW Act would establish a backstop for coal bankruptcies. It would create a standing fund for states who haven’t collected enough money to pay for reclamation, which would ensure that environmental harms are neutralized even if a coal company and its insurer couldn’t pay the costs. Under one condition: states must ensure that their bond pools are financially sound.

“In cases where the company has gone bankrupt or dissolved, there may not be adequate bonds to ensure proper cleanup. As a last resort, the RENEW Act will provide communities with a back-up source of funding for reclamation,” wrote Erin Savage of the rural advocacy group Appalachian Voices. “Otherwise, the burden of unreclaimed coal mines falls on local communities that have already given so much to provide power for the country for over a century.”

The RENEW Act arrives amidst a rising tide of interest in reviving the nation’s former energy strongholds. It came on the heels of the Infrastructure Bill, which infused a historic $11 billion into the long-struggling Abandoned Mine Lands fund, geared towards mines abandoned prior to 1977.

But unlike that measure, which drew exclusively on taxpayer dollars, solving the ongoing issue of present-day mine abandonment would commit lawmakers to demanding more from coal companies.

With a fossil fuel-friendly Republican party, that is proving to be a harder political sell. In the committee hearing, Rep. Lamb’s measure quickly became a flashpoint for the partisan divide over the transition towards renewable energy and the future of the fossil fuel industry. In a wide-ranging comment, Rep. Tom Tiffany of Minnesota broadly dismissed the set of reforms under consideration as a potential source of uncertainty in a volatile energy market. Rep. Tiffany associated the rule with the recent Securities and Exchange Commission climate risk disclosure rule, gas prices that had just reached $5 per gallon, and President Biden’s recent tariffs from Chinese solar panels.

“We got pipeline permits that are being held up. I just saw a big billboard, ‘Let’s stop natural gas from being produced in America,’” Tiffany said. “How do we have affordable energy, in what is being called this [energy] transition, if we’re shutting down those sources that are so abundant at this point?”

Rep. Pete Stauber of Minnesota addressed his witness, Todd Parfitt of Wyoming’s Department of Environmental Quality: “Let me start with a simple yes or no question: will these bills make it more difficult to produce coal needed to stave off devastating, rolling blackouts?”

“Yes,” Parfitt replied.

Though renewables’ link to blackouts is largely a myth, he’s not wrong that this reform will cost the coal industry. It will mean more financial demand in an industry struggling to find customers and insurers. But with more bankruptcies all but inevitable, says Shannon Anderson of the advocacy group Powder River Basin Resource Council, the risks of neglect could be even greater.

“If there’s a systemic failure in the industry, what do you do?” she said. “We want to make sure that communities don’t become the unpaid balance.”

The south fork of the Sangamon River in Illinois, tinted red from acidic mine drainage. Photo © Prairie Rivers Network

Laura Gersony covers water policy, infrastructure, and energy for Circle of Blue. She also writes FRESH, Circle of Blue’s biweekly digest of Great Lakes policy news, and HotSpots H2O, a monthly column about the regions and populations most at-risk for water-related hazards and conflict. She is an Environmental Studies and Political Science major at the University of Chicago and an avid Lake Michigan swimmer.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!