The President and Congress Deliver $11 Billion for Abandoned Mine Cleanups

Midwest is the target of more dollars to secure water and revive former energy strongholds.

The abandoned Horse Creek Mine near Pinckeyville, Illinois. Photo © Department of the Interior

By Laura Gersony, Circle of Blue — October 4, 2022

Part one of two in Circle of Blue’s series on abandoned coal mines. Read part two here.

Dan Fisher’s father was a coal miner. So was his grandfather. So was his wife’s father and grandfather. So was just about everyone’s grandfather in Gillespie, Illinois, a town that was born to power the Great Chicago & North Western railway system.

West of the Appalachian shadow, the Midwest isn’t thought of as coal country. But until about half a century ago, coal was king in southern Illinois. Home to the largest deposit of steelmaking metallurgical coal in the country, Illinois was one of the cradles of the nation’s labor movement. It employed hundreds of thousands of people at its peak in the 1920s. And though the number of Illinois mines has dwindled to double digits, it remains the fourth-largest coal producing state in the U.S.

Spoiled lands and waters was the cost of doing business. Coal companies routinely walked away from gaping chasms in the land, polluted streams, and deforestation. As hotspots for this early, unregulated mining, the three states which make up the Illinois coal basin — Illinois, Kentucky, and Indiana — have some of the highest environmental burdens from abandoned mines.

For the last 45 years, the U.S. chipped away at these cumulative environmental damages. Since the country began regulating abandoned mines in 1977 under the Abandoned Mine Land program, the country spent $5 billion, and about $400 million in the Illinois basin, to repair clogged and polluted streams, recontour steep highwalls, and reforest denuded landscapes.

But the program, funded by a per-ton tax on coal extraction that was not tied to inflation, was never going to be enough. The Illinois basin still has over 30,000 acres of unreclaimed land and waters, joining over 3 million acres nationwide.

(A separate program regulates mines abandoned after 1977, the subject of the next article in this series.)

In 2021, the Biden administration and Congress responded to the deficit. The infrastructure package enacted earlier this year adds $11 billion into the pre-1977 mine cleanup program to be spent over the next 15 years to finish the job. It joins the Inflation Reduction Act, enacted last month, in a renewed commitment by the country to address systemic ecological challenges and economic stress in former energy strongholds.

The latest infusion into the program, the largest in its history by far, could be enough to reclaim the vast majority of remaining pre-1977 abandoned mine sites. Accompanied by other federal and state jobs programs, it could breathe new life into affected communities, and the land and waters they depend on.

“This is huge. It is a historic investment in restoring the land, eliminating the hazards in coal country,” said Joe Pizarchik, former head of the federal Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement. “There’s been only five or six billion dollars put into reclamation over the previous 40-something years. Now you’ve got 11 billion coming in in 15 years.”

Nearly half a century after its start, the AML program produced measurable accomplishments. The program spent $4.5 billion cleaning up 5 million acres of land.

But 3 million acres—with an estimated $11 billion in damages—are still unreclaimed. Illinois has a total backlog of about 9,000 acres of reclamation, with 4,000 more in Indiana, and roughly 18,000 in western Kentucky, according to federal AML data.

Some environmental harms have been long-term and diffuse. Many old mines were retired without modern-day flooding techniques. An estimated 10 percent of emissions of methane — a gas with 34 times more planet-warming potential than carbon dioxide — come from active or abandoned coal mines. One mine in White County, Illinois that just closed is one of the country’s top 5 methane emitters.

About a third of the nation’s 4,000 hazardous water bodies on the AML list are still unreclaimed. So are 6,000 miles of clogged streams, according to federal data.

Other harms are more proximate. Disheveled land, without either the thrum of industry or the solace of the environment, represents a liability for a community struggling to find its footing as coal fades.

“When industry closes, it’s not like it packs up and leaves. You gotta deal with whatever’s left behind, like a bad divorce,” said Dan Fisher, the resident of Gillespie in Macoupin County, Illinois, a former coal stronghold.

It’s a story that Paul Robinson, a reclamation expert at the Southwest Research and Information Center in New Mexico, has seen across the country and across extractive sectors: “the company is getting the gold, the community is left with the shaft and the empty hole in the ground worth nothing.”

As former head of the federal Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement during the Obama administration Joseph Pizarchik knows well that state regulators’ experience with the program has long been defined by triage.

“States were constantly having to make difficult choices about which AML problems to address,” he said. “Based on the numbers that were coming in from the Energy Information Administration, there was never going to be enough money for states to finish reclaiming their most dangerous mines,”

Acid mine drainage at the Lead Queen Mine tunnel in Arizona. Photo © U.S. Geological Survey

Change in Fund Financing – From Private to Public

The infrastructure act’s use of taxpayer dollars to finance the AML fund marks an abandonment of the intention of the mine cleanup law. The original law made coal companies pay for the industry’s past environmental harms. It exacted a per-ton fee on coal, and funneled tax revenue to state agencies to reclaim land and waters that were damaged before the 1977 law was passed.

The roots of the deficit that soon emerged reach back to the birth of the AML program, with the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. After an era when land and water degradation was treated by polluters as externalities, SMCRA was on the cutting edge of environmental legislation that sought to internalize the costs of environmental damage.

“SMCRA focused on surface restoration: establishment of approximate original contour and post-mining land use,” said Robinson. “Those were innovative and aggressive, and derived from the concerns of people who lived in and near mines.”

The program made slow but steady progress, cleaning up about a hundred thousand acres every year. It was designed to be reauthorized every few years as needed, to finish the job.

But as market trends started signaling trouble for the coal industry, lawmakers began to demand less and less from coal companies and rely more on taxpayers to keep the fund afloat.

In recent rounds of reauthorization, Congress reduced the AML fee: the 2006 reauthorization reduced the fee by 10 percent in 2008, and another 10 percent in 2013. Accounting for inflation, the AML fee was equivalent to one-quarter of its original value, or less than half of the inflation-adjusted value of coal per ton, according to a 2020 report by the Appalachian Citizens Law Center. In 2021, the fee was lowered by an additional 20 percent.

The mid-2000s also marked a turning point in relying on taxpayers and not the AML fund to pay for cleanup. The political story behind this change in financing has a main character: the Wyoming congressional delegation. Appalachian and Midwest coal peaked decades earlier than in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, which became the nation’s largest source of coal. Wyoming lawmakers represented state coal mine operators who objected to paying into the AML fund because Wyoming has few abandoned mines eligible for AML funds.

“That disconnect between who’s paying a large share of the fee, versus where fees are used, creates an imbalance,” said Shannon Anderson, of the Powder River Basin Resource Council, a community group.

A regular tug-of-war ensued. In 2006, the Wyoming delegation pushed for an amendment, which established a new, taxpayer-funded AML revenue stream for a handful of states. In 2012, though, lawmakers from other states placed a cap on Wyoming’s AML funds after news broke that AML dollars were seen as a funding source to upgrade the University of Wyoming’s athletic facilities.

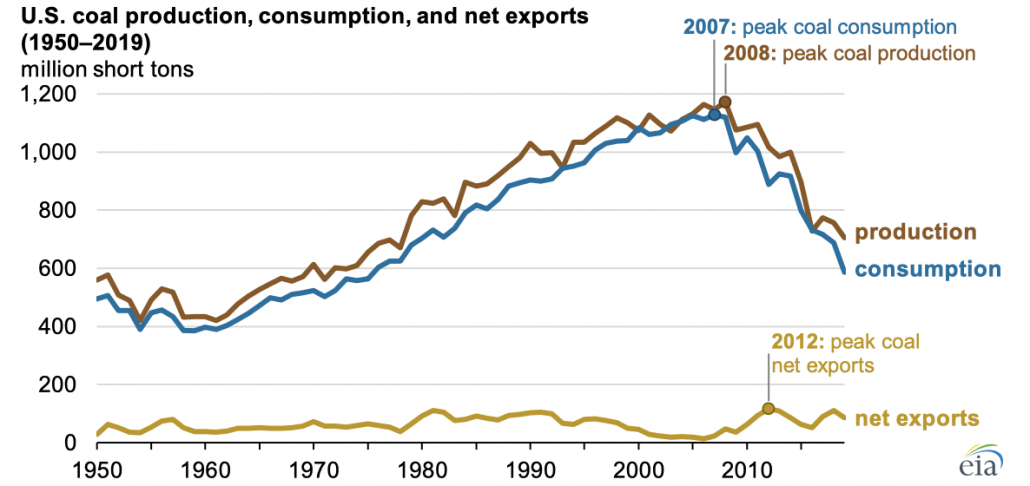

The program never scaled up again to meet demand. In recent years, the closing of coal-power electric plants contributed to the deficit of the AML program. While markets for Powder River Basin and certain Illinois coal are still strong, the shift away from coal in Appalachia and the Midwest caused overall production nationally to fall to 577 million tons last year. That’s half of total US production in 2008, when production peaked at nearly 1.2 billion tons. It’s simple math: less coal means less AML revenue.

Coal production has been in precipitous decline since 2008. Photo © U.S. Energy Information Administration

“The Best Social Binding Agent We Have”

Dan Fisher’s home town of Gillespie has been spared the downturn of the last few years: the last coal mine there closed in 1968, so Gillespie absorbed the job losses about 50 years ago. Because of reclamation law, former mine sites are now soccer fields or home to new manufacturing.

But the nation’s coal-based energy overhaul will not be as kind to other communities further south in Illinois’ heartland, where most of the state’s AML acres are located, and where a prolonged dependence on coal still prevents economic diversification: Saline County in southern Illinois is one of the 25 counties hardest hit by job losses, hemorrhaging thousands of jobs in the last decade.

Economic numbers suggest that the opportunity offered by mine reclamation is substantial. In addition to neutralizing the threat of dangers, reclaimed lands are an economic asset. Analyzing data from the Department of Interior, one study by the Appalachian Citizens Law Center estimated that the AML program, on net, supported about 4,700 jobs across the country in 2013, and added half a billion dollars to the U.S. economy that year: a 137 percent return on investment.

Even more difficult might be the socioeconomic piece of the puzzle. Fisher’s interest in abandoned mine cleanup stems mostly from his role as the founder and president of Grow Gillespie, a civic group interested in revitalizing their hometown. In conversation, Fisher comes across not with the tunnel-mindedness of most issue activists, but as something of a town historian. With a keen awareness of local history and community, he knows that mine cleanup programs could provide more than just jobs: they rebuild the culture, history, and sense of community that coal once provided.

“This is an industry in which there is a social and cultural context to it,” he said. “A melting pot of European immigrants formed this area. Coal mining was the bond that tied everyone together.”

One newer feature of AML is the Economic Revitalization program, established during the Obama Administration. It funds local investments, with the goal of “sustainable long-term rehabilitation of coalfield economies.” Things like restoring parkland to attract tourism, fixing up industrial sites to attract manufacturing, or building music and event venues. With a total budget of just over $120 million, the plan currently focuses only on Appalachian states, though advocates on Capitol Hill are pushing for its expansion to other regions.

In Illinois, new transition funding from Illinois’ recent Climate and Equitable Jobs Act has a similar goal of creating training and employment programs for displaced coal workers. Likewise, the 2021 infrastructure bill funding includes a nonbinding recommendation that states and tribes use their AML cleanup dollars to put former coal miners to work.

Coal country advocates say this is a good, if modest, start.

“Brick and mortar projects are some of the best social binding agents we have. It’s like getting a new suit, or a haircut: you just feel better about yourself, and better about your community,” said Fisher. “It’s not an accident that all of these things — the legislation, social activism, et cetera — those were by-products of the coal mines. You’ve gotta find that other thing that acts as a social engine.”

Entrance to a coal mine in Kentucky, 2011. Photo © Appalachian Voices

Laura Gersony covers water policy, infrastructure, and energy for Circle of Blue. She also writes FRESH, Circle of Blue’s biweekly digest of Great Lakes policy news, and HotSpots H2O, a monthly column about the regions and populations most at-risk for water-related hazards and conflict. She is an Environmental Studies and Political Science major at the University of Chicago and an avid Lake Michigan swimmer.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!