Visions of Solar Energy’s Future Compete in Colorado’s San Luis Valley

The U.S. government is in the process of designating more than 6,000 hectares of federal land in the nation’s highest agricultural region for solar energy development.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

SAN LUIS VALLEY, Colorado — Just as in every address that he has made to a joint session of Congress, President Barack Obama this week confirmed his commitment to the economic and environmental benefits of wind and solar energy, adding that opening more federal land to clean energy development is in the national interest.

“I’m directing my administration to allow the development of clean energy on enough public land to power 3 million homes,” the president declared in the State of the Union address on Tuesday evening.

But the government’s plan to turn large expanses of the American West into clean energy production zones is confronting considerable challenges, not the least of which is growing public resistance to big wind and solar projects that are popping up on wild lands close to rural communities. The public restiveness — driven by concerns about the effects of utility-scale installations on the environment and on small-town community values — is altering the government’s planning process and putting in doubt just how big the clean energy footprint will be on public lands.

In few places are the outlines of the opposition more clearly defined than here in the San Luis Valley, a high-altitude farming and ranching region that is the size of Connecticut. In this sunny section of Colorado, the Obama administration has designated four parcels — totaling more than 6,500 hectares (16,000 acres) and administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) — as “solar energy zones.”

“We are not against solar,” rancher Julie Sullivan told Circle of Blue. Last year, Sullivan helped defeat a large project on private land near her Saguache County home. “But we didn’t want a bad solar project, because then the bar would be lower. That would open the door to more bad projects.”

Competitive Edge and Citizen Acceptance

Indeed, as Jesse Morris, a solar analyst at the Rocky Mountain Institute, a renewable energy research and consulting group, explained in an interview with Circle of Blue, the wind and solar business is being influenced by a host of new trends in energy markets and citizen acceptance.

For instance, innovations in drilling technology and production have boosted domestic supplies of natural gas, which produces half the carbon emissions of coal and is selling at such low prices that utilities are planning new gas-fired electrical power stations. According to Morris, with such competitive pricing for electricity produced from natural gas, the economics of clean energy production could shift from big centralized solar installations to individual rooftop solar and smaller distributed systems.

In other words, big solar plants could quickly become obsolete.

“Solar is great, and we need as much of it as we can get to meet current and future energy needs,” Morris said. “The federal focus is on larger facilities. But — looking longer term — those facilities have real issues.”

— Christine Canaly, Director

San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council

In the meantime, the four solar energy zones here in the valley are joined by 13 other solar zones in five additional Western states that, three years ago, the federal government designated as prime areas to generate power from the sun. The Interior Department and a number of sister agencies are nearing the end of an environmental review, which began in 2009 and will reach another milestone on Friday, when the public comment period for the supplement to the 11,000-page draft assessment closes.

The final version will be released this summer. It will amend the BLM’s resource management plans to allow the agency to concentrate solar development in the most suitable areas.

Even through a casual reading of the citizen observations made during the first public comment period in early 2011, it becomes clear that the concerns expressed about big solar plants in the San Luis Valley are shared around much of the West. The Department of the Interior heard complaints about the negative effects of solar development on wildlife, on plants and water resources, on the fragmentation of animal migration corridors, on the cultural resources of Indian tribes, and on marred scenic views.

As a result, the department narrowed the number of solar zones to 17 from 24 and tightened the boundaries of others. The total area now prioritized for solar development on BLM-managed lands has been cut by more than half — from 273,972 hectares (677,000 acres) to 115,335 hectares (285,000 acres).

Though the Interior Department kept all four zones that had been proposed for the San Luis Valley, their total acreage was reduced by a fifth.

Sense and Sensitivity

Since 2010, the BLM has approved more than 5,600 megawatts of solar generating capacity, all in the deserts of Arizona, California, and Nevada.

Right now, a company can apply for a solar permit for any BLM land, Joe Vieira told Circle of Blue. He works on renewable energy projects from the agency’s San Luis Valley office in Monte Vista.

On conducting the latest environmental review, Vieira said, “the BLM is trying to be more strategic with where solar could be developed — finding those places with the least conflict over endangered species, views, and cultural and environmental resources.”

Two of the valley’s four zones have applications pending, Vieira said, and new transmission line capacity would be needed for all four solar zones. Because of suggestions made during the public comment period, the boundaries of three of these zones were modified and reduced. If all four zones were fully developed, the draft assessment estimates that they could support 1,450 MW using photovoltaic (PV) panels, or 2,612 MW using solar troughs.

Ceal Smith, of the San Luis Valley Renewable Communities Alliance, which supports small-scale solar development, calls the BLM plan “a giveaway to industry.” This is partly because, unlike gas and mineral leases, federal laws for wind and solar confer no financial benefits to the host community. To correct this, several U.S. senators from Western states have co-sponsored a bill that would create royalty payments for the two renewable sources based on the amount of electricity generated.

“If energy is being produced, the area needs to benefit,” said Christine Canaly, director of the San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council, a public lands advocacy group. “That mechanism is not in place for the BLM zones.”

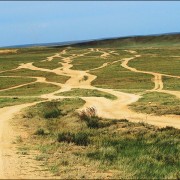

Instead of developing thousand-acre tracts of public land, Smith suggested putting solar panels on degraded private land or in the empty corners of fields that are irrigated by the legions of center-pivot systems in the valley. That course of action would minimize land disturbance and help transition marginal fields away from excessive groundwater use that is draining one of the valley’s aquifers and affecting the holders of senior surface rights.

— Julie Sullivan

Rancher in San Luis Valley

Portland, Oregon-based Iberdrola Renewables, for instance, built a 30-MW photovoltaic array last year on 90 hectares (220 acres) that were once used to grow carrots and potatoes. Whereas the crops would have consumed at least 270,000 cubic meters (220 acre-feet) of water each year, said Richard Sparks, an irrigation agronomist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, the solar plant will use almost none — just a small amount for the bathroom and the kitchen in the operation center, according to Iberdrola spokeswoman Jan Johnson.

On the other hand, solar thermal systems, which use much more water, could put additional strain on the valley’s water resources and traditional land patterns. The authors of the draft environmental assessment anticipated potential conflict, writing that “the transfer of agricultural water rights for solar energy development will result in agricultural fields being put out of production and will significantly alter land use in the San Luis Valley.”

Who Benefits?

The San Luis Valley has long supported small solar projects installed on homes and businesses. But, as Julie Sullivan tells Circle of Blue, few residents of the San Luis Valley are anxious to support a “bad” solar project that could “open the door to more bad projects.”

By bad, Sullivan is referring to a utility-scale project that a decade or so ago would have been widely cited in the national environmental community as beneficial. In this case, it was a 200-megawatt facility proposed by Tessera, a Houston-based company. Initial plans called for a fleet of 8,000 solar dishes, each 12-meters tall (40-feet tall) with Stirling engines to convert the sunlight into electricity.

Sullivan points from her dining room window to the horizon, where the Tessera solar dishes would have stood out against the freshly powdered Sangre de Cristo Mountains. This time last year, neighbors representing ranching, agricultural, and environmental groups were meeting in her home to discuss how to stop the project.

“I never thought I’d be fighting solar power,” says Sullivan, who taught environmental studies at Lesley University before marrying into the ranch life. “But it was an industrial project in an agricultural area. The renewable industry wants us to think that anything ‘renewable’ is green, and it’s not.”

Last July, the company abandoned the project, citing noise levels that exceeded state limits. Defeating the installation marked something of an opening salvo by opponents in what will be a long-running struggle for residents and the federal government to define what a “good” solar project is and to shape solar development here, in the nation’s highest agricultural region.

A Solar Mini-boom

Another hotspot for solar development in the valley is Alamosa County, to the south of Saguache. Because the valley’s transmission substation is in Alamosa, four projects — 87 MW in total — have been built on private land there, providing financial benefits to the county.

Both Smith and Canaly said that Alamosa County had decided to keep projects relatively small — the largest two are 30-MW facilities on no more than 90 hectares (220 acres). They are popular because they make good use of existing grid space and reap tax benefits, which ultimately help local citizens, said Smith and Canaly.

While solar development on the valley’s public land awaits the conclusions of the Interior Department’s environmental review this summer, private landowners have been leasing or selling land to energy companies. A pair of 100-MW solar thermal plants, each with a 200-meter (656-feet) energy-storage tower, are proposed for 1,600 hectares (4,000 acres) in Saguache County.

On February 2, the county’s board of commissioners will hold a public hearing to discuss the latest application from SolarReserve, a Delaware-based company.

This article was prepared while the author, Brett Walton, participated in a fellowship that was paid for by the Institutes for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!