While South Carolina Floods, U.S. Wrestles With Urban Stormwater

Lawsuit requires EPA to address one of the largest water pollution sources in the country.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

Among the devastating effects of the low pressure storm system that pummeled South Carolina over the weekend was the heavy damage the record-breaking rains caused to water transport and treatment infrastructure, and the release of a tide of contaminated stormwater. Water mains burst in Columbia, the state capital. The Congaree River broke through a levee holding it back from the city’s drinking water supply. Nearly 40,000 people statewide could be without water for days.

The bruising deluge, which South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley called a once-in-a-millennium event, focuses attention on the most persistent and troubling water pollution problem in the country—water that rushes off cities, suburbs, and farmland that carries pollutants into the nation’s waters. The South Carolina floods, moreover, come as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is preparing to propose new rules tightening stormwater oversight in small towns and cities across the country.

In a settlement approved September 16 with the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Santa Barbara-based Environmental Defense Center, the agency agreed to update regulations governing urban stormwater runoff in municipalities with fewer than 100,000 residents. The deal requires the EPA to propose a new rule by December 17 and to finalize a rule by November 2016.

–Richard Horner, professor

University of Washington

The settlement is the latest chapter in a nearly three-decade trudge by the EPA, scientists, and environmental organizations to pull stormwater under the auspices of the federal Clean Water Act. The act, originally created to address end-of-pipe pollution from factories and sewage plants, has not been updated since 1987. Regulating stormwater represents a pivotal test of the country’s ability to transition the foundational law to confront the diffuse sources of chemicals, fertilizers, and sediments that now account for the vast majority of water pollution.

So far, efforts to update the nation’s clean water protections are being pursued almost entirely by the White House. On September 30, the EPA finalized new rules for power plant effluent that limit the amount of toxic metals the plants can discharge into waterways, and in August, a controversial rule came into effect that clarifies which waterways fall under the Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction.

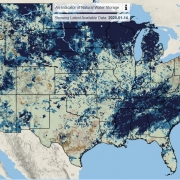

But the last major directive on stormwater came from Congress. In 1987 legislators ordered the EPA to include stormwater under the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System, the Clean Water Act’s primary permitting tool for improving water quality. The agency prepared rules for large cities in 1990, but did not pull small cities into the permitting system until 1999. The EPA now registers NPDES stormwater permits for 750 large cities, while 6,700 small cities are gathered under general NPDES permits, most of them administered at the state level. Still, progress toward achieving water quality improvements has been slow, and urban stormwater runoff continues to impair nearly 100,000 kilometers (62,000 miles) of rivers and streams nationwide, according to the National Water Quality Assessment.

Agricultural runoff, the water that washes over fields and carries soil and nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into the nation’s waterways, is an even larger problem—it impairs nearly 240,000 kilometers (149,000 miles) of rivers and streams and more than 404,000 hectares (1 million acres) of lakes, ponds, and reservoirs. It is also the principal cause of vast, toxin-producing algae blooms in Lake Erie that threaten municipal drinking water systems. Agricultural runoff is still virtually exempt under the Clean Water Act, much as urban stormwater was before 1987. However, challenges to the law that seek to categorize agricultural tile drainage systems as point sources of water pollution could put it on a similar track toward stricter regulation.

The reason stormwater was overlooked for so long can be traced to deeply ingrained thinking about water management in U.S. cities, researchers and advocates told Circle of Blue, where the primary goal of stormwater infrastructure has long been to move runoff away from urban areas as quickly as possible. It is also the result of a regulatory system, designed to address factory and municipal waste coming from distinct point sources, that is ill-suited to effectively manage the quantity of stormwater pouring in from a growing urban landscape during stronger, more frequent storms.

“The permit system is a vestige now. It was developed for earlier sewage and industrial problems,” said Richard Horner, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Washington and a member of the National Research Council board that, in 2008, found deep flaws in the way EPA regulates stormwater. “They are rightly considered to be true point sources, but now it’s spread over the entire landscape. The EPA was not very imaginative when it slapped the same permit program [on stormwater].”

Changing Urban Stormwater Regulations

Urban stormwater runoff, in its simplest terms, is rain that falls onto hard surfaces like parking lots, roads, and sidewalks, where it can’t soak into the ground. As the rain washes into storm drains and out to rivers and streams, it picks up chemicals, oils, sediment, and other pollutants, and the sheer volume and velocity of the water often scours away riverbanks and disturbs aquatic life.

Efforts by cities to control stormwater date back to the Mesopotamian Empire, and most cities in the United States collect rain runoff in municipal separate storm sewer systems, referred to as MS4s. The MS4s are networks of storm drains, gutters, and pipes that eventually discharge the untreated water at sewer outfalls. Until 1990, large cities—those with more than 100,000 residents—did not need pollution discharge permits for stormwater sewer systems, and small cities were not placed under the permitting program until 1999.

“They had kind of fallen through the cracks of the Clean Water Act,” Larry Levine, a senior attorney for the NRDC, told Circle of Blue. “There had been debate since the 1970s about whether they needed to be covered or not. In the mid-80s, it was determined that Congress would set deadlines for EPA to develop rules. At that point, ultimately it was established that the Clean Water Act did require them to get a permit.”

–Larry Levine, senior attorney

Natural Resources Defense Council

“This absolutely existed and they were discharging pollution all those years,” Levine continued. “Regulation was slow to catch up with it, and it really took litigation over many years to force EPA to grapple with that.”

Current stormwater regulations require cities to create and implement stormwater management programs with the goal of reducing pollution to the “maximum extent practicable”. Cities are expected to achieve pollution reductions by applying best management practices, which range from measures to improve public education to methods to reduce erosion at construction sites. The regulations do not, however, dictate which BMPs cities must use. In addition, while large cities are usually covered by individual NPDES permits tailored to their specific stormwater system, small cities most often fall under general permits that cover large geographic areas, sometimes state-wide.

In 2001, a coalition of environmental plaintiffs, including the NRDC, argued that oversight of stormwater management practices was not stringent enough to protect water quality. The lawsuit set off more than a decade of appeals and subsequent legal action that resulted in this month’s settlement.

“EPA ought to be setting a floor really for what it means to be controlling pollution to the maximum extent possible,” Levine said. “ That would go a long way to giving some teeth to that Clean Water Act standard instead of leaving it entirely up to the judgement of each individual municipality.”

The NRDC is not calling for every small city to have an individual permit, Levine said, but would like to see regulations that make certain BMPs and green infrastructure components a requirement rather than an option. A 2008 National Research Council review of the EPA’s regulatory program for stormwater also proposed extensive changes to the way permits are issued and enforced. Most notably, the authors suggested shifting permits away from political boundaries and toward a system that reflects the realities of watersheds, where pollutants from a range of cities collectively impair water quality in the same rivers and streams.

“That’s another way to get economies of scale—if water flows to the same point in the same river, you can build something in cooperation and share the cost,” the University of Washington’s Horner said. “And the monitoring that needs to be done, you could share that cost, and so on.”

Green Infrastructure Aims to Keep Stormwater In Place

One of the biggest challenges to effective stormwater management, however, is the massive quantity of runoff cities face, according to Horner.

“Of course people think about the many pollutants that are in the water, which come from all the activities on the landscape. But what people don’t think about so much is that it’s not just the quality of the water, it’s the quantity,” he told Circle of Blue. “More water drains off impervious surfaces, which means more water flowing in the streams at high rates for longer times, and that itself is stressful to the aquatic life.”

In response, researchers, environmentalists, and the EPA itself are promoting methods to keep more water where it falls by planting rain gardens and bioswales, installing permeable pavement, and creating green rooftops. This green infrastructure attempts to reduce the amount of water passing into storm drains in the first place, an about-face from traditional gray infrastructure that is a conduit from cities to streams.

“In about the mid-90s, the concept of low impact development came along—that is, an attempt to reduce the amount of water by infiltrating it, evaporating it, or just capturing or using it in some way, and then cleaning up anything that is left,” Horner said. “That has been developing over the last 20 years. There have been a number of installations and some progress, but population growth and urbanization has outstripped it.”

–Derek Booth, professor

University of California, Santa Barbara

While some cities, such as Chicago, Los Angeles, and Oakland are embracing green infrastructure, stormwater management regulations do not require cities to implement it. A significant obstacle to wider adoption of green infrastructure practices is the cost of applying it to landscapes that are already heavily developed, according to Derek Booth, a professor in the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at the University of California, Santa Barbara and another member of the 2008 National Research Council study. Cities can require new developments to include green infrastructure in their design, but have little leverage to force existing private buildings and residences to make upgrades. Additionally, public funding for green infrastructure projects is often squeezed in areas without designated funds for stormwater.

“Smaller jurisdictions and any jurisdictions that don’t have a stormwater utility fee can only pay for the stuff out of the general fund,” Booth told Circle of Blue. “So stormwater is competing with cops and firemen and libraries and schools. It is rare that stormwater is raised to an equivalent priority in the minds of most citizens. I’m not saying that’s wrong, but if stormwater management is slugging it out with those basic community health and safety services, it’s not going to do very well.”

Existing development is also an obstacle to a stormwater management approach that relies solely on green infrastructure.

“It means we either need to pull ourselves back farther from these channels than we have traditionally thought was necessary or considered reasonable, or we’re going to have to do something more,” Booth said. “Because I think what green infrastructure gives us at its best or near best is a recovery of the natural hydrological runoff process. Which from an ecological perspective is fabulous, but that still doesn’t mean there’s never any out-of-bank flows.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

The Stream, October 7: Private Sector Investment Encouraged to Finance Australia...

The Stream, October 7: Private Sector Investment Encouraged to Finance Australia...

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!