Plumbing WikiLeaks: Water’s Role in U.S. Foreign Aid

Diplomatic cables show that the U.S. State Department aims to strike a balance between the need for diplomatic dances and the desire to produce tangible results from on-the-ground projects.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

As thousands of government representatives, academics, industry officials, and environmental organizations gathered in Istanbul in March 2009 for the water sector’s largest convention, the head U.S. State Department official from the Istanbul consulate debated the value of the laborious meeting and how its goals squared with national policy, according to a diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks.

In a cable intended for Steven Pierce, a senior policy advisor at the time for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Sharon Wiener of the Istanbul consulate seemed clearly dissatisfied with the Fifth World Water Forum. The Forum had brought together 25,000 participants from 155 countries, including more than 100 ministers and several heads of state, yet Wiener dismissed the nonbinding declarations of high-level delegates and the World Water Council, the convention’s sponsoring body, as virtually valueless.

“The World Water Council,” she wrote, “has long believed that the [Forum’s] key outcomes are the numerous declarations made by heads-of-state, ministers, parliamentarians, and others. We disagree.”

Pessimistic or Realistic?

Wiener’s cable provides a candid assessment of the current rules of diplomatic engagement – an often frustrating, cumbersome, time-soaking allegiance to process and propriety that diplomats in the trenches say yields little in return, other than agreement among nations to keep on meeting.

But do U.S. government actions in the water sector confirm Wiener’s position?

“Every time ministers get together, you have to ask, ‘How much upside is there? How much can really be accomplished?’ And that’s what the cable gets at,” says John Oldfield, the managing director of WASH Advocacy Initiative, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization working to increase global access to drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).

Though the seemingly endless stream of draft statements and revisions can wear thin one’s patience with the process, the World Water Forum and other such horse-trading sessions are sometimes necessary to create the political space for material progress to occur, Oldfield told Circle of Blue. The U.S. government, he added, is doing well as it walks that line.

Delay, Delay, Delay, Dead

Essentially, Wiener, then the U.S. Consul General in Istanbul, had advocated that water should factor into U.S. foreign policy through decisive action — rather than a series of nonbinding agreements that may never be signed. Her cable was sent to a senior policy advisor in the office of the administrator at USAID, whose budget is one of the primary vehicles for water-sector funding.

She was concerned that the nonbinding agreements typically signed at such events took up enormous amounts of time and resources, though they offered little assistance to the lives of those they were meant to help.

For instance, this time around, things had gone awry when senior government officials had convened on March 17, 2009, to finalize preparations for the ministerial meetings, at which time, an agreed-upon ministerial statement would be signed. Instead of moving forward, many delegations had pressed to re-open the draft declaration for a variety of reasons, including transboundary water issues, human security, and the human right to water — which, she noted, the U.S. was “one of only a few countries [to] vocally oppose.”

Though the draft declaration “was far from perfect,” Wiener noted, it had been the product of a “long, transparent, fully consultative preparatory process [in which] all governments were invited to participate, but not all did.” Besides that, she pointed out, any declaration made would be nonbinding, as had been those signed at previous Forums.

In spite of all this, the draft was never formally adopted because it had become clear through the back-and-forth process that many paragraphs would have to be renegotiated, meaning additional time and resources would have to be devoted to the document. Several delegations — notably Bolivia, Switzerland, and Japan — had, in turn, expressed strong dissatisfaction with the process and had “vowed to bring these concerns into the ministerial meetings.”

Because these negotiations, along with signed statements from former years, had added little to the “international discourse” on water and sanitation, Wiener asserted that “the [Forum’s] strength and focus should be on those activities that can meaningfully advance projects and programs that make a measurable contribution to the lives of people on the ground. This includes the number of people trained, the number of new partnerships launched, and the additional resources mobilized.”

Walking the (Financial) Line

When assessing the 250,000 memos that are available online via WikiLeaks, a nonprofit organization that accepts leaked government and corporate documents, it becomes clear through the water-related notes — of which there are quite a few — that the U.S. leadership is responding to global water challenges, pushing scientific partnerships, training technocrats in international law and policy, and assisting water negotiations.

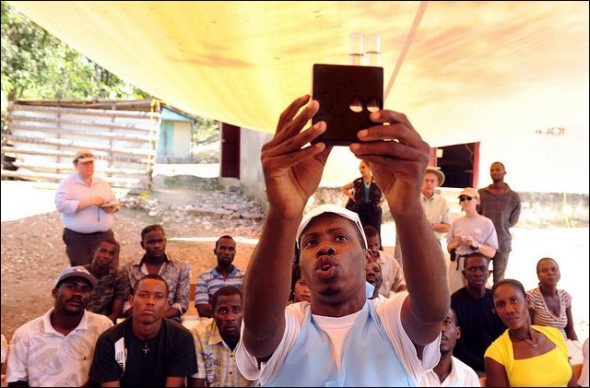

U.S. assistance can range from helping other countries with adaptation to changing environmental and political conditions to helping with the implementation of adequate sanitation and clean sources of drinking water.

“I’ve seen good progress,” Oldfield said of his 10-year experience in the WASH sector, “with both high-level ministerial meetings and on-the-ground support from the U.S. government regarding water and sanitation. Everything they’re doing is trending in the right direction.”

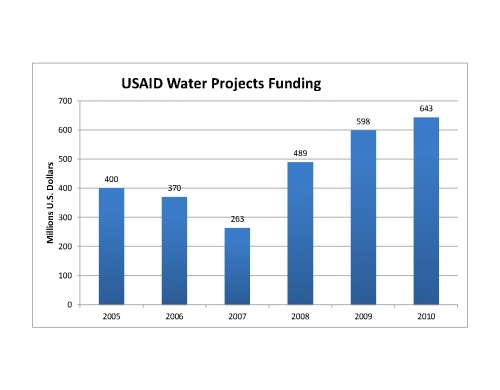

To buttress his point, Oldfield noted that the USAID water-projects budget has steadily increased recently. Preliminary figures from the 2011 fiscal year, however, point toward lower spending, but a final sum will not be available until next June.

Oldfield also mentioned that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton gave a water-policy speech in March 2010 at the National Geographic Society’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. In that speech, Clinton referred to five “streams” of diplomatic focus:

- Coordinating aid efforts among players in the international water sector

- Improving managerial and technical skills in partner countries

- Supporting scientific knowledge and technical innovation

- Creating new partnerships with non-governmental organizations and the private sector

- Providing money for projects

The financial boost for many of these goals came from the 2005 Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act, which established water and sanitation as priorities for U.S. foreign aid.

Tangible Outcomes and Coordinating Productivity

Additionally, water projects are now a pivotal part of the U.S. diplomatic mission for Afghanistan and Pakistan. Last year, the U.S. government developed a water strategy for Pakistan, and there are plans to spend billions in the coming years on irrigation, hydroelectric power, and systems for supplying drinking water. (The problems caused by inadequate water treaties in the region will be discussed in the next edition of the Plumbing Wikileaks series.)

With the potential cut in the USAID water-projects budget this year, Oldfield said that the recession — coupled with the Congressional push for austerity — has changed the way the Obama administration is approaching foreign aid.

“This administration is more focused on wringing as much value out of foreign assistance as possible,” Oldfield said. “There’s more monitoring, more evaluation, and a greater focus on the sustainability of projects. There’s a little more training and capacity building, and there’s fewer direct services, such as well-drilling.”

Despite these achievements, the money spent on water aid could be more productive if agencies coordinated their activities, according to several government reports.

For instance, a November 2010 assessment from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) looked at U.S. water projects in Afghanistan. The GAO found that, though the U.S. has created several interagency working groups, the Department of Defense (DOD) and USAID lack a central database to share project information.

Similarly, an October 2011 report from the DOD stated that fragmented planning between U.S. embassies and defense command posts has resulted in “broad and undefined” programs for water security and climate change adaptation. The report recommended a more coherent leadership structure, clear goals, and shared data.

Likewise, a cable written February 10, 2010 from the U.S. embassy in Ethiopia to several State Department agencies reveals that the U.S. government’s non-profit partners in the water sector complained about the timing of funding cycles and restrictive earmarks.

Under Secretary for Global Affairs Maria Otero traveled to Addis Ababa to meet with representatives from CARE, Save the Children USA, the International Rescue Committee, and Merlin, a British health charity.

The aid groups, according to the cable, said that they need longer, multi-year grants in order to develop community relationships and properly implement projects. They also said that the earmarks put too much emphasis on reporting the number of people served instead of permitting innovative project designs.

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. This is the second in a series called Plumbing Wikileaks, in which Walton examines the 250,000 memos available in the online Wikileaks catalog in search of water-related stories. Click here to read the first in this series, Saudi Arabia Fears Iranian Nuclear Meltdown and Potential Terrorism to Desalination. Contact Brett Walton

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

IRIN Middle East | IRAQ: Seeping sewage hits Fallujah residents …

14 Jul 2010 – Fallujah’s infrastructure was in ruins after battles between US forces and Sunni … Waste pours onto the streets and seeps into drinking water supplies. … is the main pipeline that sends all the waste to the main processing unit, …

Water: Wealth & Power

The Secret Behind the Sanctions: How the U.S. Intentionally Destroyed Iraq’s Water Supply