Ogallala Groundwater Study Will Set Stage for Colorado Water Conservation Debate

Farmers want to know the economic and social ramifications of reducing groundwater use.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Following a regional trend, Colorado’s water board is likely to approve a $US 160,000 grant on Friday that will help farmers in the state’s northeastern plains reckon with a water-scarce future.

Researchers at Colorado State University will use the state funds to answer a simple but profound question that is blowing across the American Great Plains like a stiff wind: What does water conservation mean for farming families, their towns, and their livelihoods?

Requested by the Water Preservation Partnership, a coalition of a farm group and all of the region’s water management districts, the two-year academic study reflects an important development in the nation’s grain belt.

–Chris Goemans,

Colorado State University

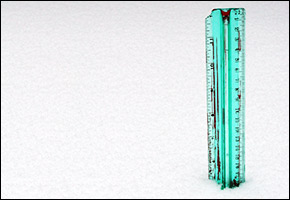

The region’s primary water supply is the Ogallala Aquifer, which lies beneath parts of eight plains states and is the largest underground source of fresh water in the United States. With little moisture soaking into the ground and high-volume pumps sucking out water around the clock during the summer irrigation months, large sections of the aquifer will eventually be too low to irrigate millions of acres of corn, soybeans, and wheat. The last few years of drought have produced record annual drops in the water table, adding a distressing urgency to the matter.

“There is concern now over the rate of pumping,” Chris Goemans, an agricultural economist at Colorado State and one of the study leaders, told Circle of Blue. “The question is, what do we do and what happens if we do that?”

If current practices continue, wells in some counties will be dry within a decade, with disastrous economic and social consequences for rural communities. Faced with this prospect, the people of the plains, from Nebraska to Texas and now Colorado, are beginning to tighten the spigot and embrace, sometimes grudgingly, water conservation.

Less Water Now, More Water Later

The Water Preservation Partnership, which recently marked its first anniversary, was created to find a local solution to the problem of groundwater depletion. It takes as a model a similar grassroots success story in northwest Kansas.

“The goal is to work together to find methods for conserving the precious lifeblood of our basin,” Deb Daniel told Circle of Blue. Daniel is general manager of the Republican River Water Conservation District, one of 10 members of the partnership.

Eight of the partners are groundwater management districts. Farmers in these districts account for 80 percent of the water used in northeastern Colorado and half of regional economic output. Altogether, the nine-county region withdraws nearly twice as much water each year as filters back into the aquifer, according to recent research. The annual deficit is 488 million cubic meters (396,000 acre-feet), roughly twice what Denver uses in a year.

–state grant application,

Water Preservation Partnership

The members see the writing on the wall for the aquifer if current behaviors continue, and they support a reduction in water use. Doing so will keep water in the ground longer, but not forever. The demands of irrigation are far too great. Still, the farmers want a clearer idea of the changes that conservation might bring.

“The WPP believes we must follow the lead of groups in Kansas, Texas and elsewhere who have developed grassroots, self-governing policies, by imposing pumping policies upon ourselves,” the members wrote in their application for state funding. “The challenge is determining what the policies should be, taking into consideration their economic feasibility for our agricultural producers and rural communities as well as their regional support.”

That is where the study comes in.

Researchers at Colorado State University, which will contribute $US 48,000 to the project, will develop four products. First, they will use computer models to analyze the relationship between water use and agricultural production over the next 100 years. Several levels of conservation will be assessed, showing a range of possible outcomes.

Farmers in northwest Kansas, for example, are in the second year of a five-year plan to reduce water use by 20 percent. Their economic performance under the restrictions is being assessed by Kansas State University in a separate, ongoing study.

Next, the Colorado State University researchers will fan out into the community to educate farmers about the results of the modeling.

Then farmers will take a survey that asks what types of policies they prefer for achieving the reductions in water use. Goemans, the economist, said that policies will fall into one of two categories: those that put a price on water and those that put a cap on how much farmers use.

Lastly, the researchers will combine the modeling results and the survey preferences in a set of recommended policies.

“The study will be huge to getting public buy-in, when the farmers see the numbers about what happens if we choose conservation,” Daniel said.

Other states have also used academic studies to highlight the benefits of saving more water for later. A 2013 Kansas State University analysis showed that farm output in the Kansas section of the Ogallala Aquifer would be greater through the end of the century if farmers cut water withdrawals immediately by 20 percent.

The Colorado State University study has the conditional support of the state water board, said Rebecca Mitchell, head of the water supply planning section.

Mitchell told Circle of Blue that approval of the grant on Friday is “likely” though the state wants to see a few more letters of support to ensure the project has wide appeal. The board itself is interested, viewing the study as a template for analyzing water conservation policies in other areas of the state.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!