Great Lakes Toxic Algae Prompts Big Investment and Rare Political Agreement

After last summer’s toxic algae outbreak, safe drinking water is a priority again in Ohio, the state that spurred the Clean Water Act more than four decades ago.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

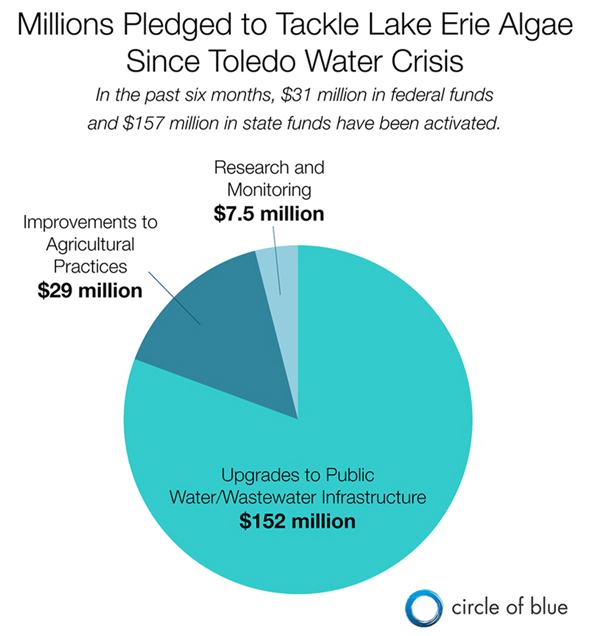

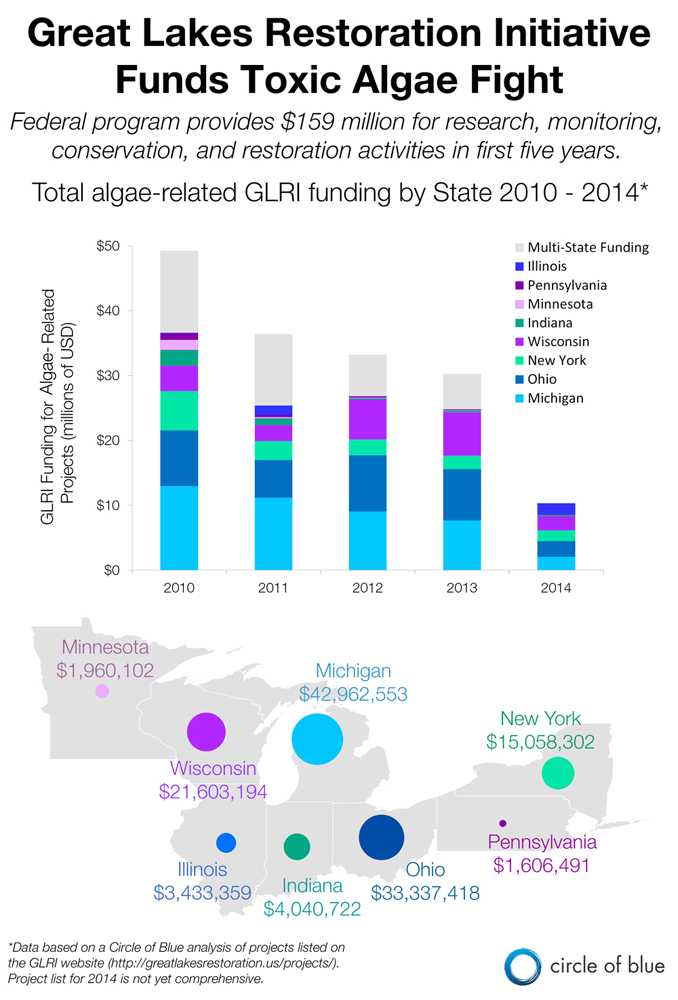

State and federal lawmakers have mobilized more than $US 188 million since last August to understand and respond to the toxic algae outbreaks in Lake Erie that poisoned the water supply for 500,000 people in Toledo, Ohio. The surge in algae-related spending over the last six months doubles the amount that has been directed over the past four years to the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) for addressing the causes of toxic algae outbreaks, a serious pollution and public health threat across the basin.

In all, more than $US 336 million have been invested by Ohio and the federal government to clear Great Lakes waters of the nutrients that are the primary cause of the algae and microcystin toxins which are poisoning water. Managed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the algae-reduction program is a facet of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, one of the largest investments in environmental research, conservation, and recovery in the United States. It follows in the footsteps of focused contemporary projects to reduce water pollution in the United States like the Chesapeake Bay Program and the plan to restore Florida’s Everglades.

–Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio)

U.S. Senator

“These projects and funds are a first step — not a silver bullet — to solve the problem of harmful algal blooms,” said U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), who helped direct federal funds to the Great Lakes states, in a statement to Circle of Blue. “We also need the EPA to issue guidance on microcystin now, and we need to be sure communities have the resources to update antiquated sewer systems.”

The program is a display of the powerful public concern about contaminants in drinking water.

While both major political parties disagree about almost every major issue, dirty drinking water is an important departure. The Great Lakes algae project is the work of a Democratic president and a Republican governor, and it has bipartisan support in both the U.S. Congress and the state legislatures.

The project also is the latest reflection of Ohio’s prominence in regional and national clean water policy and practices. In the 1940s, Ohio lawmakers and scientists were instrumental in developing water pollution control regulations to stem contamination in the Ohio River. Those regulatory innovations were influential in developing central provisions of the 1972 federal Clean Water Act, the nation’s most important water-quality statute. Three years prior to the Clean Water Act’s Congressional passage, the Cuyahoga River caught fire in Cleveland, a signal event that alerted the nation to the seriously degraded quality of American rivers, lakes, and bays.

Along with steps to deal with poisoned algae, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) includes the clean-up of toxic industrial sites, efforts to control invasive species, and conservation projects to protect native species and habitat. Over the last five years, spending on these steps has injected more than $US 1.6 billion into the Great Lakes region.

President Obama’s new budget, released this week, proposes a $US 50 million cut to the program’s funding level for 2016, but previous attempts to scale back the GLRI have failed in Congress. The program will receive $US 300 million this year. Last fall, the project’s leaders completed a new strategy plan to guide GLRI priorities for the next five years. That action plan outlined, for the first time, goals for reducing harmful algae blooms and the phosphorus pollution that drives them.

–David Schindler, scientist

University of Alberta

Scientists and other experts, however, have long warned that an investment strategy is not enough to rid the lakes of toxic blooms.

They say regulations that include agriculture — the source of nearly two-thirds of the phosphorus that is causing Lake Erie’s algae blooms — are also needed under the federal Clean Water Act, which currently addresses only urban phosphorus pollution in a meaningful way.

“They said, ‘No, we invested enough money in the problem. We’ve signed an agreement now. We’ve declared that eutrophication will go away,’” said David Schindler, a scientist at the University of Alberta, in an interview with Circle of Blue last fall. Dr. Schindler produced landmark experiments on Canadian lakes in the 1960s that identified phosphorus as the key driver of algae growth in fresh water. “Now, with increasing populations, we have used more and more fertilizer, grown more and more livestock on the land, and turned more and more natural ecosystems into concrete jungles. And all of those things have increased these nonpoint sources. The politicians can’t really claim that no one told them this was likely to happen.”

Lawmakers seem reluctant to impose regulations to reconcile the economically and politically powerful agriculture industry with drinking water safety.

But new legislation introduced in Ohio this year could begin to change that. The proposals — which call for restrictions on the timing of fertilizer application, stricter rules for the disposal of dredged lake sediment, and the creation of a new algae-management office — set up a significant test for the state at a time when drinking water in the United States is once again under assault from chemical and oil spills, nitrate pollution, and aging infrastructure.

–Adam Rissien, director

Ag and Water Policy, Ohio Environmental Council

“It’s going to require some very nuanced legislation,” said Adam Rissien, director of agricultural and water policy at the Ohio Environmental Council, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “We talk a lot about the need for studies. But there is also a need for action. We have enough studies that have recommended actions, and I think it is time we start moving on some of those.”

Ohio Senate Bill Would Ban Spreading Manure on Frozen Ground

First in line is SB 1, a bill introduced this week by Ohio State Senators Randy Gardner (R) and Bob Peterson (R). The legislation revives many of the provisions that were proposed in a state senate bill at the end of 2014, including a clause that would ban farmers from spreading manure or fertilizer on frozen ground. Unlike the previous bill, which died in December, SB 1 focuses solely on controlling nutrient pollution from farms and combating algae blooms. In addition to the manure ban, SB 1 would:

- Transfer the Agricultural Pollution Abatement Program from the Department of Natural Resources to the Department of Agriculture.

- Create an Office of Harmful Algae Management and Response within the state’s Environmental Protection Agency.

- Establish requirements for the disposal of dredge material, nutrient loading, and phosphorus testing by public water utilities.

- Include an emergency clause that would make the law effective immediately.

The bill, as well as all of the funding that has been pledged in the last six months, is a good start, according to Ohio State Representative Mike Sheehy (D).

“We need to go in to look at this bill and see if it’s going to do all of the desired things to bring down the level of phosphorus that’s occurring in the Western Basin of Lake Erie every spring, because that’s the goal we’re driving at right now,” Sheehy told Circle of Blue. “If this legislation starts to address that, I’m going to support it. But if there are loopholes and some people don’t have to comply, I’m going to fight that. Everyone here in the House of Representatives, and in the Senate, and certainly the governor — all of them are talking about the need to address this problem. Hopefully we can get something done early here in the 131st Assembly.”

Farms Support Safe Drinking Water and Regulation with Caveats

The urgency of the problem is being echoed by leaders in Ohio’s agriculture industry, which has largely supported initiatives like the potential manure ban and a fertilizer-application certification program, required by legislation last year.

–Mike Sheehy (D)

Ohio State Representative

“Farmers have known for a while that we have some challenges. But when you wake up one morning and nearly half a million people can’t drink their water, it quickly screams to the top of the priority list,” said Joe Cornely, senior director of corporate communications for the Ohio Farm Bureau, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “So it served as a wake-up call that, something we knew we needed to be working on, it needed to become more of a priority.”

In the short term, the Farm Bureau is working with state and federal funding programs to help farmers to implement best management practices in areas where nutrient reductions will have the biggest, quickest effect on algae blooms, Cornely said.

While there is support for some regulation, he emphasized that one of the biggest concerns is knowing which management practices are most effective. Research into this question — known as “edge-of-field” studies — is being conducted by a number of Ohio agencies and universities with funding from the state, as well as the agricultural community.

“We have to be cautious and smart about the steps we take so we don’t fix one set of problems and create another,” Cornely said. “We are very confident that it is not either/or. We’re not going to choose between producing food and having clean water; we think we can have both. Unfortunately, getting there, there are no flip-the-switch solutions. We can’t just make everything perfect tomorrow.”

Federal Funding a ‘Shot-in-the-Arm’ for Farmers

Federal dollars will help put some of the practices that are known to reduce nutrient runoff — such as buffer strips and control structures that manage when water is released from tile-drainage systems — on the ground in the western Lake Erie basin. Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana received $US 17.5 million from the Regional Conservation Partnership Program to assist farmers with financial and technical resources.

–Joe Cornely, senior director

Ohio Farm Bureau corporate communications

“It certainly is a huge shot in the arm, and it is on top of some state efforts and other federal efforts,” Steve Davis told Circle of Blue. Davis is a watershed coordinator with the Natural Resources Conservation Service in Ohio. “At same time, this is a 7-million acre watershed.”

“The RCPP funding will help identify important points at which runoff becomes a problem and will help with the development of best management practices in agriculture,” Senator Brown said. “This targeted approach will have significant long-term benefits.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!