Toledo Issues Emergency ‘Do Not Drink Water’ Warning to Residents

Algae toxins poison Lake Erie; 400,000 people without water.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

8/4/2014 Update:Toledo City Government Declares Water Safe

Residents of Toledo can safely use their tap water for drinking, according to a government release lifting the “Do Not Drink” advisory.

“Effective immediately, customers of the City of Toledo Public Water system may now safely drink tap water. Consistent test results have shown Microcystin no longer exceeds the recommended drinking water warning of 1 microgram per liter standard set by the World Health Organization in testing done by the City of Toledo, the Ohio EPA and the US EPA,” the release says.

Residents who used no water for any purpose over the weekend were advised to flush their household lines. Residents who used water for toilets, showering, and other non-consumptive uses were not required to flush their lines. The city also asked all residents to conserve water “to help our water treatment plant as it returns to full operation.”

The City of Toledo has issued a “Do Not Drink” advisory for residents served by Toledo Water after chemical tests confirmed the presence of unsafe levels of the algal toxin Microcystin in the drinking water plant’s finished water. The advisory, spanning three counties in Ohio and one in Michigan, leaves more than 400,000 people in the Toledo area without drinking water.

“Do not drink the water,” Melanie Amato, public information officer for the Ohio Department of Health,” told Circle of Blue. “You can shower in it, bathe in it, but do not try to ingest it. That means no washing dishes; you can brush your teeth with it as long as you don’t swallow any water, but we recommend using bottled water for that as well.”

“Do not drink the water.”

–Melani Amato

Ohio Department of Health

The Toledo advisory was posted at 2:00 Saturday morning. Ohio governor John Kasich soon announced a state of emergency to mobilize more resources for the city.

Other emergency measures also became apparent across northwest Ohio:

- Stores sold out of bottled water, sending residents into neighboring cities and Michigan to find supplies.

- Local restaurants, universities and public libraries closed.

- Several nearby municipalities that have not been affected by the toxin are offering water to Toledo residents free of charge.

- The National Guard is charged with delivering 300 cases of bottled water from Akron, Ohio, as well as Meals Ready to Eat (MRE’s) for distribution to homeless shelters and other vulnerable populations who are unable to cook with their water.

- Humanitarian organizations like the American Red Cross are responding, manning water distribution centers and providing water delivery assistance to homebound residents.

“[The bloom] is surrounding where the Toledo water intake pipes are.”

–Justin Chaffin

Stone Laboratory

Microcystin is a toxin produced by blooms of freshwater algae, which are a vast and growing problem in Lake Erie—Toledo’s drinking water source. Microcystin can cause nausea, vomiting, and liver damage if ingested, and it has been known to kill dogs and livestock that drink contaminated water. Skin contact with the toxin can also cause irritation and rashes, though levels in treated water are not high enough at this time to warrant a complete ban on water use, Amato said.

Microcystin appears to be a growing public health problem in the western portions of Lake Erie. Almost a year ago, in September 2013, Carroll Township near Toledo detected dangerous levels of Microcystin in its water supply, shut down its water treatment plant, and simultaneously alerted the community’s 2,000 residents not to drink the water.

Toledo is the first major city in the Great Lakes region to fall victim to Microcystin contamination, despite testing and treatment for the toxin. The city allocated $US 4 million for water treatment chemicals last year—double what it spent in 2010. The spending increase is largely due to concerns about algal toxins. City water managers were especially worried after the Carroll Township crisis, which was alleviated by the township’s ability to connect to an outside water supply while it flushed the toxin from its own system. It is unclear if Toledo has similar options available. The city’s Facebook page states:

“It is understandable that there is a huge degree of public concern, but we would advise everyone to remain calm, an alternative water supply and a distribution system will be announced as quickly as possible.”

Algal Bloom Small, But Concentrated

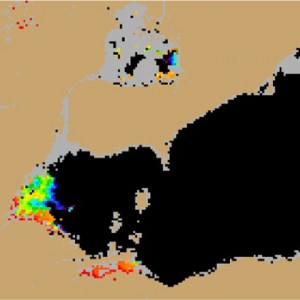

The culprit behind Toledo’s drinking water problems is a toxic algal bloom in Lake Erie’s Maumee Bay. The bloom is not very large compared to past blooms, and Microcystin levels, though high, are not out of the range of those previously seen on the lake.

“The bloom right now isn’t big in terms of spatial coverage, but it is pretty dense in Maumee bay and that area of western Lake Erie,” Justin Chaffin, a senior researcher at The Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory in Put-in-Bay, Ohio, told Circle of Blue. “It is pretty much surrounding where the Toledo water intake pipes are.”

The bloom in that area is very concentrated and thick, he added.

“I’m not sure what levels they were seeing coming in through their pipes, but we were out there sampling on Wednesday and we got Microcystin levels around 10 to 20 parts per billion.”

The acceptable level of Microcystin in drinking water is 1 part per billion, according to the World Health Organization. Typically, the city of Toledo is able to chemically treat their drinking water to bring Microcystin levels below that threshold, even if the intakes receive high levels of the toxin. Chaffin said that there was likely a mixing event—such as a storm or strong wind—that forced the toxic algae, which normally floats on top of the water, down to the bottom where the intakes are located.

The city is now hurrying to test water samples drawn from throughout the treatment and distribution system to track the Microcystin concentrations. Testing a batch of samples takes approximately three to four hours once the test is started, according to Chaffin.

“They are running water samples from hospitals, really from all over Toledo,” he said. “Everyone that does Microcystin sampling in the Toledo area is either sending their [test] kits to the Oregon [Ohio] treatment plant or the city of Toledo’s treatment plant. They are just swamped with samples and they were running out of kits.”

Toledo is also sending water samples to labs in Cincinnati to undergo a more complete analysis. There are approximately 80 different kinds of Microcystin-producing cyanobacteria, Chaffin said. Although all are toxic, their level of toxicity varies. The more extensive tests will help to determine a more accurate level of the toxin in the water.

Algal Blooms a Growing Problem

“Until we reduce phosphorus and address harmful algal blooms, I’m afraid it’s going to come on the ratepayers’ backs.”

–Adam Rissien

Ohio Environmental Council

Commonplace in Lake Erie in the 1960s, toxic algal blooms disappeared from the lake following international, national and state efforts to reduce the phosphorus pollution that drives them. The federal Clean Water Act of 1972 was especially important for reducing phosphorus from city sewage plants and other “point” sources that discharged pollutants from a pipe. The CWA, however, did little to address phosphorus runoff from farms and lawns, known as “nonpoint” sources. Researchers have shown that a rise in phosphorus levels—particularly a form of the nutrient that is readily available to promote algae growth—has coincided with renewed blooms in Lake Erie, and international agencies have called for a reduction in phosphorus to alleviate problematic blooms in Lake Erie and elsewhere in the Great Lakes. The largest bloom ever recorded on the lake occurred in 2011. Scientists and environmental groups say addressing agriculture is particularly important for reducing the blooms.

“I have every confidence in the water treatment plant to figure out how to make the drinking water safe,” Adam Rissien, director of agricultural and water policy at the Ohio Environmental Council, told Circle of Blue.“Unfortunately, the options available to them are costly and that means a rate increase—there’s no way around it. Until we reduce phosphorus and address harmful algal blooms, I’m afraid it’s going to come on the ratepayers’ backs. And that’s not fair.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Thanks for the great article. It is, by far, the best article I have seen on today’s problem.

Toledo, Ohio is the seat of Lucas County, where nearly all of the people live who are unable to drink water from the city’s water treatment plant due to microcystin contamination.

A long-awaited upgrade to that plant is estimated to cost $321 million.

Taxpayers in Lucas County have paid over 1.6 billion to fight the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, five times the cost to provide safe drinking water to a half-million people.

Mike Ferner, Toledo City Councilman 1989-93, former Navy corpsman and national president of Veterans For Peace

Toledo, Ohio

Stagnant water produces dangerous anaerobic toxins like microsystin.com

Aeration is the only practical solution to stagnant water elimination.

It is unclear if Toledo has similar options available. The city’s Facebook page states:

“It is understandable that there is a huge degree of public concern, but we would advise everyone to remain calm, an alternative water supply and a distribution system will be announced as quickly as possible.”

I work at the Collins Park Water Treatment plant in Toledo. There is no alternate option other than bringing in bottled water and leeching off of neighboring systems like Bowling Green and Oregon. This was a ticking time bomb and it went off.