Q&A: Jonathan Waterman on Running Dry

Welcome to Circle of Blue Radio’s Series Five in 15, where we’re asking global thought leaders five questions in 15 minutes, more or less. These are experts working in journalism, science, communications design and water. I’m J. Carl Ganter. Today’s program is underwritten by Traverse Internet Law, tech-savvy lawyers representing Internet and technology companies.

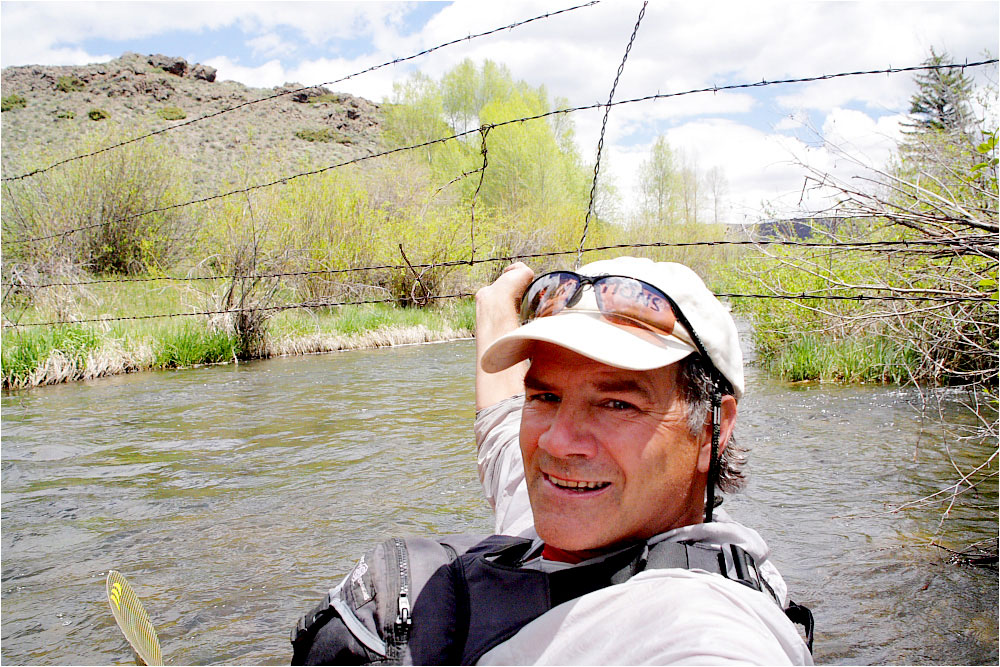

Our guest today is Jonathan Waterman, author of “Running Dry: A Journey from Source to Sea Down the Colorado River.” Since the 1993 paddle down the Gulf of California, starting at the mouth of the Colorado, Waterman has been fascinated by the river and alarmed by the demands being placed on its waters. He returned to the American Southwest’s iconic river in 2008. He lived on its waters for five months, paddled its length and then walked when the river ran out.

It was in 1998 when the Colorado stopped flowing to the sea as it had done for millions of years before. It had been sucked dry miles short of the Gulf by a growing demand for drinking water in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Phoenix and Tucson, and for agricultural use by farmers up and down its 1,500-mile length. Waterman talked with us about his trip, the many threats facing the Colorado and ways that he feels we can help.

Also, in a more general way, I’ve been doing long journeys for 30 years now, and I’ve had the luxury, maybe the tenacity, to engage myself in landscapes and get to know a place by traveling and by sleeping out, and covering broad sweeps of the land and ocean coastline, and rivers. I wanted to do that same kind of thing with the Colorado River — get to know it by living on the river for months at a time. But my trips have always been to far, remote places. I wanted to do something close to home that impacts the future not only of myself and my children, but of all the 30 million people who depend upon the river. I wanted to give an up-close and personal view.

It’s not the only place to go, and farming, of course, is the central drain of the Colorado River. Seventy-eight percent of the water goes to agriculture in the Colorado River Basin. It’s a great place to begin because if farmers could implement more sustainable, farsighted — not even farsighted, but relatively technology-wise — simple drip irrigation, it would have immense savings. Those savings, of course, could be realized by municipalities that use a lot less of the water, but as the population continues to increase, places like LA, Vegas, Denver, even Albuquerque, Phoenix, Tucson, Salt Lake, all of those places depend to a greater or lesser extent on Colorado River water. If they all began sustainable xeriscaping in replacing front lawns, the savings there, too, would be immense.

I’m really concerned that the public at large…even the 30 million people who depend upon the river don’t understand the issues of the river. There’s a lot of talk, even most recently from former Secretary of the Interior, that there is no scarcity of water in the Southwest. Nothing could be further from the truth. We’re in times of drought. The drought continues, even with big snow years the last three years, where I live. It doesn’t matter. The warming temperatures cause tremendous evaporation. We have a coming train wreck on our hands.

I did speak to some farmers along the way. Fortunately, the man whom I spent the most time with was in one of the biggest irrigation districts on the entire river, called Imperial Valley, in California, and he had converted 7 percent of his fields to drip irrigation. And the savings were enormous. Despite the initial costs, he is implementing more and more drip irrigation on his fields. This is the future, and this is the kind of reform that we need to see, but it’s going to take some leadership. Not many of our leaders have such conflicting interests that they can’t seem to focus on the river as a whole, the river as a living being that flows not just for the sake of Denver or Phoenix, but it flows to reach the sea.

We’ve been speaking with author Jonathan Waterman. And his new book, “Running Dry: A Journey from Source to Sea Down the Colorado River,” is in stores now. To find more articles and broadcasts on water, design, policy and related issues, be sure to tune in to Circle of Blue online at 99.198.125.162/~circl731.

This interview was performed by Heather Rousseau and produced by Steve Kellman. Our theme is composed by Nedav Kahn. Circle of Blue Radio is underwritten by Traverse Legal, PLC, Internet attorneys specializing in trademark infringement litigation, copyright infringement litigation, patent litigation and patent prosecution. Join us gain for Circle of Blue Radio’s Five in 15. I’m J. Carl Ganter.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Jon, I just found letters that you wrote to me back in 1980. I was helping my Dad and siblings clean out my parents home in Tuscaloosa, Al. as my Mom died 4 years ago and Dad remarried. How are your parents? Do you ever get back to Lexington or keep in touch with high school folks?( I don’t.) I’m living in Ct. and have 2 boys, 21 and 19. My younger one just finished his 2nd year at Boulder and older is finishing up at U of Connecticut. How many kids do you have? Enjoyed reading about your trip down the Colorado River.I didn’t know you were an author, but knew you were an “outdoorsman”, climber, and all. E-mail me back if you’re not too busy; my life’s pretty chaotic as a solo private practice physical therapist. My best to you and family.

Theresa Partlow