The Walled Grave: Politics of Neglect Caused Zimbabwe’s Cholera Outbreak

Grim consequences of failed water and sanitation infrastructure

by Sarah Haughn?

Circle of Blue

UPDATE: Find the full interview with Professor Timothy Burke here.

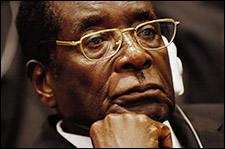

The vicious cholera epidemic sweeping across Zimbabwe is the result of a systemic breakdown in basic sanitation, social services, and economic stability that began decades before Robert Mugabe came to power, according to the United Nations, as well as historians and sociologists familiar with the situation.

The United Nations estimates that over 20,000 people have contracted cholera since the outbreak erupted in August. More than 1,000 have died. Moreover, a meltdown in Zimbabwe’s economy –- people and businesses are confronting the highest rate of inflation ever encountered — makes it impossible for all but a few of the country’s residents to afford medical treatments that could easily cure the bacterial infection. Cholera spreads in food and water, attacks the small intestine, and causes deadly diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration.

Experts at the World Health Organization assert that the outbreak stems from poor environmental management. Many global news organizations contend that the country’s collapse and the cholera epidemic really began when President Robert Mugabe decided to wrest land away from white settlers and give it to indigenous Zimbabweans. Professor Timothy Burke, a scholar of African studies at Swarthmore College with an interest in Zimbabwe, says the breakdown really started during British rule.

Mugabe, he says, came to power in 1980 and inherited an already crumbling water and sanitation system from the British. “Colonial governments throughout the region, including the Rhodesian government, had a consistent aversion to the construction of even minimal water and sanitation infrastructure in the townships in which Africans were allowed to live,” said Burke.

Burke pointed out in an interview with Circle of Blue that “after the colonial subjugation of Zimbabwe in 1890, several successive phases of land seizure by white rulers tended to move African farmers to more arid areas of the country, with more marginal soils. So there was a ‘politics of water’ involved in this case as well.”

The most dramatic and disturbing modern day result is Zimbabwe’s cholera crisis. The disease has spread through teeming urban slums with deplorably degraded water, sewer, and sanitation infrastructure. The WHO reports that at least 50% of cholera cases have afflicted those in suburbs of capital city Harare. Experts at the WHO suggest that 60,000 residents could soon be at risk of infection. International news reports describe taps that have run dry, sewer lines that have ruptured with raw human waste, and garbage fermenting on the streets.

It is a picture of environmental degradation, social disorder, and human despair that is globally urgent and historically significant. Lawyers, doctors and nurses are on strike. Teachers cannot afford the bus fare to reach their schools. There are reports of soldiers rioting.

A Prosperous Past

But Zimbabwe has not always been a place of such suffering and destruction. In fact, even its name celebrates a capacity to create. During the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries the country was home to a society of stonemasons and cattle herders who built a stunning complex of mortarless granite walls spanning 1,800 acres. British and French explorers who discovered the walls initially attributed their construction to foreign powers, believing the indigenous people incapable of such complex construction.

Zimbabwe — formerly referred to as Southern Rhodesia under British rule, and then simply as Rhodesia under the infamous regime of white settler Ian Smith — takes its current name from the ancient civilization. In Shona the word dzimbabwe means house of stone, grave of a chief, or walled grave, referring to the stone ruins of Great Zimbabwe.

Over the course of recent history, Zimbabwe benefited from its commitment to health and education. A majority of its population can read. Although the number of literate people has been decreasing over the past several years, Zimbabwe continues to boast one of the highest literacy rates in the world.

The country also developed impressive food production and manufacturing sectors. During the 1980s it was lauded as southern Africa’s breadbasket, an impressive African success story. Until very recently, manufacturing provided more than a third of the nation’s revenue. Zimbabwe for much of the last few decades was the second most industrialized country on the African continent, behind South Africa.

Water, Land and Race

So how did a country known for its ancient architecture, fertile valleys, and history of robust economic expansion sink into such tragic disrepair? To understand Zimbabwe’s breakdown requires an understanding of its history — both as a former colony of Great Britain and as a young nation trying to reinvent its identity after decades of land-based ethnic segregation. Much of the story can be told through the politics of land and water.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, British colonizers pushed black Africans to dryer parts of the country. Meanwhile, those living in the nation’s cities were relegated to urban slums.

From country to city, indigenous communities lacked proper water and sanitation services. “The reasoning behind this deliberate failure to build infrastructure was that Africans were supposed to be ‘temporary’ residents in urban areas,” says Burke, “and to build even minimal infrastructure of this kind would have been an admission that urban populations were permanent. So even given the corruption of the postcolonial Zimbabwean state, they inherited a water and sanitation infrastructure that was in many respects deliberately crippled and lacking capacity.”

Mugabe’s government, according to Burke, dedicated little effort to improving the already inadequate infrastructure. “At the very least, by the early 1990s, the government was already beginning a process of ‘hollowing out’ key government departments, using them largely as a dumping ground for patronage jobs while paying little heed to the need to deliver effective services to the public,” he says.

Burke explains that corruption occurred in the shadow of land reform. “There was very little investment made in expanding the capacity of public services or infrastructure where expansion was needed, and funds for maintenance of existing infrastructure were poorly spent or diverted to an increasing degree as the 1990s wore on. In many ways, the controversy over land reform was a calculated attempt to divert international and local attention from the acceleration of internal corruption. This affected water and sanitation as much as any other area of service.”

More Suffering Anticipated?

Not surprisingly, as Zimbabwe survives another year of drought, unprecedented inflation, and a worsening cholera outbreak, calls for Mugabe’s resignation sound more urgently than ever. Mugabe is fighting back. He asserts that the U.K. is using the outbreak of disease to wage war in the country and oust him from power.

Although the stress on the economy and the human suffering suggests that Mugabe’s regime is failing, Burke maintains that even if the Zimbabwe leader fell, little would improve.

“What I think global observers don’t understand about Zimbabwe,” he says, “is that it is presently an undeclared military dictatorship. I don’t mean to minimize Mugabe’s own personal authority and political skills. He continues to exert a surprising degree of personal control, using some of the tactics that he has employed his entire life.

“But the effective power behind the scenes is a small set of military officers and police commanders. They are the ones who do not want to allow the opposition to take power, or to allow any serious reform to take place. They also have very little interest in improving governance or services, only in protecting their own wealth and power from scrutiny.”??

Sarah Haughn is a reporter and writer for Circle of Blue, the online independent news organization covering the global freshwater crisis. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!