Q&A: Giulio Boccaletti on the Sustainable Development Goal for Restoring Water Ecosystems

Giulio Boccaletti is the global managing director for water at The Nature Conservancy. He talks with Circle of Blue about the Sustainable Development subgoal to protect and restore water-related ecosystems and how it represents a shift in thinking about how to provide communities with safe water.

In a series of Q&As with water experts, Circle of Blue explores the significance of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for water, how they can be achieved, and how they will be measured. We spoke with Giulio Boccaletti about the 6.6 subgoal, which aims, by 2020, to “protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes.”

Giulio Boccaletti: One of the things that the [SDG] has done is really articulate the integration of things that typically are quite separate. In the past, you would have one group worrying about water access and drinking water, another group worrying about water infrastructure like reservoirs, and then a third group worrying about the ecological health of biologically-based systems. These seem to be pretty disparate issues. What the SDGs have done is bring all this together. It’s the recognition that making sure that wetlands are functioning, making sure rivers are healthy as ecological systems, that their function is intact, that outcome is part of the overall issue of delivering sustainable water services to humanity. That’s an important shift because it essentially recognizes what some people call natural infrastructure, that the most fundamental piece of water infrastructure we have is the stuff we inherited.

That’s one way of thinking about what that last subgoal means. The other effect is that it actually turns the camera around. This is true for all the SDGs, but particularly the water one. If you look back to the Millennium Development Goals, they were very much focused on the delivery of services to the least developed countries. It was about equity and lifting people out of poverty through a set of goals, and water was a part of that. What this set of goals is doing is sustainable development writ large. It applies to the developing world as well as the developed world. Middle income countries like Brazil are having water resources issues, but equally California, which is probably the richest place on the planet. And it’s having the same issues.

Giulio Boccaletti: I think the urgency is mostly about us. That’s the source of it. The good news about freshwater ecosystems is, in some ways, it’s a positive story. The Ohio River in the U.S. was way more polluted than it is today. Before the Clean Water Act was passed, the United States had watershed outcomes that were much worse than they are today. It’s not a one directional story. We know how to do this, we know how to restore an ecosystem. While we may not recover all of what was lost, and someplace like the Mississippi River may never look like it did 200 years ago, we can still restore a lot of its functions.

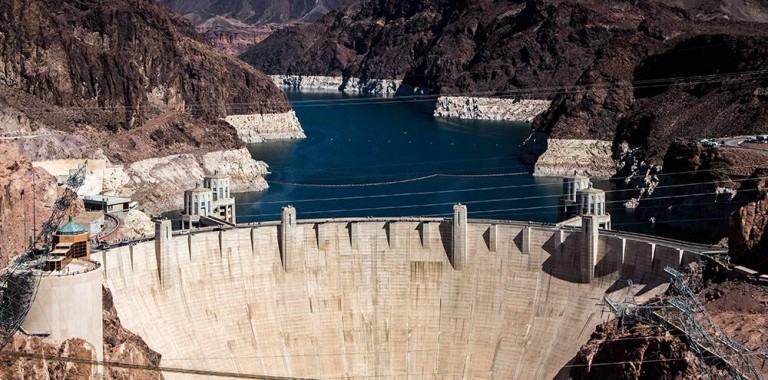

Last year, when they released water down the Colorado River to restore the connection to the sea, the moment the water touched the Delta, it completely revived. In a way, that’s the most obvious demonstration of how nature is actually resilient. It’s not a question of whether you care about nature or not, which we do, but the bigger problem is our population is growing and we need a whole bunch of things that we will struggle to deliver if we don’t regain the balance between ecological needs and human needs. Having healthy ecosystems is a precondition of supplying sustainable services. I think that is the fundamental shift the SDGs are trying to frame.

Giulio Boccaletti: The challenge is that it introduces some degree of complexity. You might end up having a very simplistic view that nature is simply competitive to human uses. But in someplace like the Murray Darling, it is a very particular kind of ecosystem. Nature is used to periods of floods followed by periods of drought. I think there is a lot of opportunity to be very precise about what are the actual needs of nature.

In setting up an institution, if you use Australia as an example, it manages it because of a market system that allows you to be quite precise. We don’t have that level of precision in most of the world, whereas they have an engineered system. We have the opportunity though to get really consistent and precise—what is it really that nature needs? The ecosystem services that nature provides, whether protection from floods, or nitrogen fixation in the environment, typically those processes, as natural infrastructure, fit the low-end of the water cost scale.

Giulio Boccaletti: It’s very spotty, and the answer is very contextual. Things that worked 100 years ago don’t necessarily work 100 years later, and, frankly, climate change throws a wrench in the plan. What might have been a perfectly viable setup in the environment isn’t when the statistic of rainfall is changing. That complicates it. There are some countries that have done better than others in part because it was easier or because they wanted to do that.

This is one of the defining challenges for much of the developing world—will they be able to meet the recipes that are implied by the SDGs? If they did, what they would do is leapfrog from the path that much of the developed countries followed.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!